PART III | BUL IN A CHINA SHOP: LEE BUL’S PARADOXICAL CYBORGS

EMBODYING AMBIGUITY

A defining feature of cyborg theory is a commitment to confusing and destabilizing socially constructed categories, thus opening up infinite possibilities for meaning. Donna Haraway stated this in her manifesto:

“The cyborg is resolutely committed to partiality, irony, intimacy, and perversity. It is oppositional, utopian, and completely without innocence.”[113]

Lee Bul’s cyborg sculptures are similarly dedicated to confusion and ambiguity, and the range of scholarly and critical responses to them are evidence of this. While Kurzmeyer characterized these cyborgs as “sad female knights,” Randy Lee Cutler described them as “hard, seductive, and Amazonian.”[114] Simultaneously alluring and grotesque, the scope of responses these sculptures elicit encapsulates some of their essential qualities: their ambiguity and ability to evoke a multiplicity of interpretations.

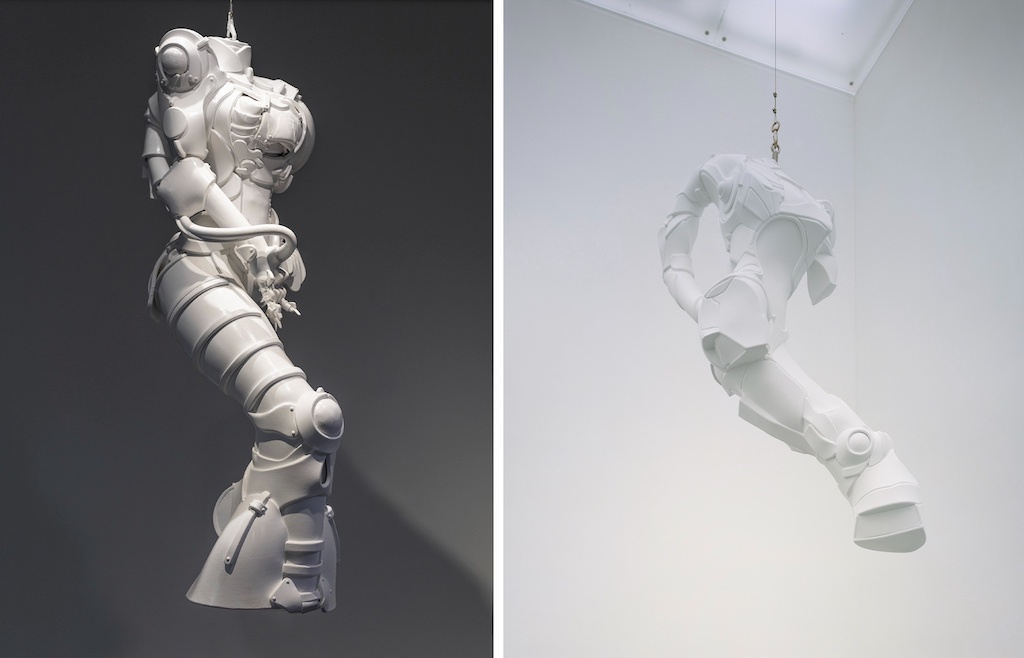

The sculptures are undeniably threatening, exhibiting spiky appendages and militaristic armor. The hands of Cyborg W1-W4 all have sharply pointed fingers, suggesting claws or pointy nails, often associated with villainous characters in both American and East Asian culture.[115] Many are over six feet tall and ominously loom over the viewer when hung, and some, like Cyborg W3, even seem frozen in a moment of dynamic, aggressive action. But this menacing impression is instantly destabilized by elements that give the sculptures a sense of victimhood. The fragmentation of their forms, which are missing heads and limbs, implies violence enacted on their bodies, despite their heavy armor. The connection between bodily violence and fragmentation is especially apparent in Cyborg W9 and W10, where the rounded ends of their severed limbs resemble those of amputees, or soldiers who have lost their limbs in battle. The allusion to militarism in their design only heightens the sense of enacted bodily violence. However, the specific violence they reference is unclear, whether they refer to the disproportionate violence that people with female bodies face or the violence of war. Additionally, the presentation of the sculptures as hung evokes a multitude of associations with victimhood, or perhaps at least immobility. Lee’s performance of Abortion involved the hanging of her own body to recreate the physical, social and emotional pain of an abortion, suggesting a connection with her cyborg sculptures. If the act of hanging a body from the ceiling is connected with pain for the artist (and those familiar with her work), that pain is evoked here. The hanging cyborgs suggest motionless puppets, meat hanging in a butcher shop, or when hung low, perhaps victims of the gallows.

Even an identification of the figures as bodies at all is ambiguous. Overlapping panels, tubes, and apparatuses, all in the same color and material, confuse the eye and obscure the human-like form of the sculpture. When viewed from different angles, some of the sculptures, like Cyborg W5 (figure 40), for example, become abstracted and lose their association with the human body completely. Cyborg W8 is similarly abstracted. Presented as fragmentary and not whole as we imagine a body “should” be, they destabilize our notions of what a human body looks like. They each bear signs of individuality, yet they are decapitated, severed from their identity. They hover somewhere between human and object provoking feelings of both identification and distance.

In this way Lee Bul’s cyborgs are a perfect embodiment of cyborg theory, which delights in the undefined, ambiguous, and hybrid. They are contradictory and resistant to categorization, opening up multiple possibilities for connection and interpretation. They pose poignant questions about our existence in the age of technological mediation: what is a body, and what does it look like? What does a female body look like? What makes a human? And how does our interaction with technology change us and how we exist in the world? However, these observations of the sculptures in the context of cyborg theory are limited, showing the ineffectiveness of cyborg theory in art historical application. A deeper understanding of the series requires an investigation of their visual forms and methods of display in order to conclude if it represents a feminist take on the female cyborg form.

Figure 28: Lee Bul, Cyborg W3, 1998. Cast silicone, polyurethane filling, paint pigment, 185 x 81 x 58 cm. Photo: Yoon Hyung-moon. Courtesy of the artist.

Figure 34 (left): Lee Bul, Cyborg W9, 2006. Hand-cut EVA panels on FRP, polyurethane coating, 180 x 60 x 70 cm.

Figure 35 (right): Lee Bul, Cyborg W10, 2006. Hand-cut EVA panels on FRP, polyurethane coating, 180 x 70 x 60cm.

Figure 40 (left): Lee Bul, side view of Cyborg W5, 1999. Hand-cut EVA panels on FRP, polyurethane coating, 150 x 55 x 90cm.

Figure 33 (right): Lee Bul, Cyborg W8, 2004. Hand-cut EVA panels on FRP, polyurethane coating, 181 x 65 x 115 cm. Photo: Atsushi Nakamichi/Nacása & Partners. Photo Courtesy: 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa.

A defining feature of cyborg theory is a commitment to confusing and destabilizing socially constructed categories, thus opening up infinite possibilities for meaning. Donna Haraway stated this in her manifesto:

“The cyborg is resolutely committed to partiality, irony, intimacy, and perversity. It is oppositional, utopian, and completely without innocence.”[113]

Lee Bul’s cyborg sculptures are similarly dedicated to confusion and ambiguity, and the range of scholarly and critical responses to them are evidence of this. While Kurzmeyer characterized these cyborgs as “sad female knights,” Randy Lee Cutler described them as “hard, seductive, and Amazonian.”[114] Simultaneously alluring and grotesque, the scope of responses these sculptures elicit encapsulates some of their essential qualities: their ambiguity and ability to evoke a multiplicity of interpretations.

Figure 28: Lee Bul, Cyborg W3, 1998. Cast silicone, polyurethane filling, paint pigment, 185 x 81 x 58 cm. Photo: Yoon Hyung-moon. Courtesy of the artist.

The sculptures are undeniably threatening, exhibiting spiky appendages and militaristic armor. The hands of Cyborg W1-W4 all have sharply pointed fingers, suggesting claws or pointy nails, often associated with villainous characters in both American and East Asian culture.[115] Many are over six feet tall and ominously loom over the viewer when hung, and some, like Cyborg W3, even seem frozen in a moment of dynamic, aggressive action. But this menacing impression is instantly destabilized by elements that give the sculptures a sense of victimhood. The fragmentation of their forms, which are missing heads and limbs, implies violence enacted on their bodies, despite their heavy armor. The connection between bodily violence and fragmentation is especially apparent in Cyborg W9 and W10, where the rounded ends of their severed limbs resemble those of amputees, or soldiers who have lost their limbs in battle. The allusion to militarism in their design only heightens the sense of enacted bodily violence. However, the specific violence they reference is unclear, whether they refer to the disproportionate violence that people with female bodies face or the violence of war. Additionally, the presentation of the sculptures as hung evokes a multitude of associations with victimhood, or perhaps at least immobility. Lee’s performance of Abortion involved the hanging of her own body to recreate the physical, social and emotional pain of an abortion, suggesting a connection with her cyborg sculptures. If the act of hanging a body from the ceiling is connected with pain for the artist (and those familiar with her work), that pain is evoked here. The hanging cyborgs suggest motionless puppets, meat hanging in a butcher shop, or when hung low, perhaps victims of the gallows.

Figure 34 (left): Lee Bul, Cyborg W9, 2006. Hand-cut EVA panels on FRP, polyurethane coating, 180 x 60 x 70 cm.

Figure 35 (right): Lee Bul, Cyborg W10, 2006. Hand-cut EVA panels on FRP, polyurethane coating, 180 x 70 x 60cm.

Even an identification of the figures as bodies at all is ambiguous. Overlapping panels, tubes, and apparatuses, all in the same color and material, confuse the eye and obscure the human-like form of the sculpture. When viewed from different angles, some of the sculptures, like Cyborg W5 (figure 40), for example, become abstracted and lose their association with the human body completely. Cyborg W8 is similarly abstracted. Presented as fragmentary and not whole as we imagine a body “should” be, they destabilize our notions of what a human body looks like. They each bear signs of individuality, yet they are decapitated, severed from their identity. They hover somewhere between human and object provoking feelings of both identification and distance.

Figure 40 (left): Lee Bul, side view of Cyborg W5, 1999. Hand-cut EVA panels on FRP, polyurethane coating, 150 x 55 x 90cm.

Figure 33 (right): Lee Bul, Cyborg W8, 2004. Hand-cut EVA panels on FRP, polyurethane coating, 181 x 65 x 115 cm. Photo: Atsushi Nakamichi/Nacása & Partners. Photo Courtesy: 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa.

In this way Lee Bul’s cyborgs are a perfect embodiment of cyborg theory, which delights in the undefined, ambiguous, and hybrid. They are contradictory and resistant to categorization, opening up multiple possibilities for connection and interpretation. They pose poignant questions about our existence in the age of technological mediation: what is a body, and what does it look like? What does a female body look like? What makes a human? And how does our interaction with technology change us and how we exist in the world? However, these observations of the sculptures in the context of cyborg theory are limited, showing the ineffectiveness of cyborg theory in art historical application. A deeper understanding of the series requires an investigation of their visual forms and methods of display in order to conclude if it represents a feminist take on the female cyborg form.

[114] Randy Lee Cutler, “Warning: Sheborgs/Cyberfems Rupture Image Stream,” in The Uncanny: Experiments in Cyborg Culture, ed. Bruce Grenville (Vancouver: Vancouver Art Gallery, 2001), 192.

[115] This is a common trope in visual media across cultures, dubbed “femme fatalons” by trope-based encyclopedia TV Tropes. Characters who exhibit femme fatalons are almost always villains, and examples include Yzma from the Disney film The Emperor’s New Groove, Maleficent from Sleeping Beauty, and Lust from the anime “Fullmetal Alchemist: Brotherhood.” See the TV Tropes website for more examples.