by Anna Moore

The Environment and MMIW

Exploring the narrative of MMIW and native environmental relationships.

How are they connected?

To understand the violence seen against native lands is to understand the threat of violence to native women. Indigenous communities are connected to their land and environment.

U.S. colonialism has been perpetuated through environmental abuses.

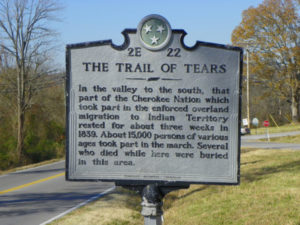

- For Indigenous populations, having land is more than just ownership. The land of native populations connects people to culture, spirituality, and identity. In some of our earliest histories as a country, native people have been violently removed from that connection. Modern examples are pipeline protests as mentioned above.

To enforce change on native people’s livelihoods through removing them from their land was a monumental moment the oppressive history that has permanently changed lives where culture, identity, and environment was lost.

U.S. colonialism has been perpetuated through gender violence (MMIW).

- For Indigenous women, gender violence and assault is not a new trend. Through early conquests, colonizers have used gender violence as a weapon. With native bodies being referred to as “dirty” and “impure” they were never safe from violence. For colonial oppressors, this held belief of native bodies being of less worth translated into “rapeable” bodies.

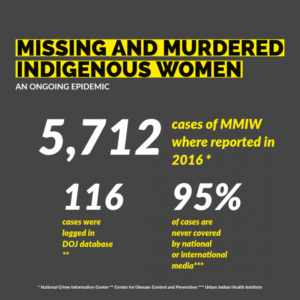

- Efforts to map the MMIW cases have been oppressed due to the lack of resources and attention from the DOJ. In 2018, Annita Lucchesi, a PhD candidate at the University of Lethbridge, discussed her efforts to map North America’s MMIW. Her estimates include that since the beginning of the 20th century, 25,000 native women and girls have gone missing.

Native people’s connection to land is an essential aspect of being. The constantly violence seen against the land can be tied to the epidemic of violence against the women and girls connected to the same culture and identity lost through violence toward native lands.

Native people’s connection to land is an essential aspect of being. The constantly violence seen against the land can be tied to the epidemic of violence against the women and girls connected to the same culture and identity lost through violence toward native lands.

Understanding the protest and dissent toward environmental and gender injustices draws another connection.

Comparing the two→

- Increased criminalization of indigenous protest is seen toward environmental injustice

- Example- Sept. 3rd 2016, 200 water protectors gathered in peaceful march and were encountered with bulldozing of ancestral burial site, guards with attack dogs that bit indigenous water protectors

- Violent language and lack of investigation/reporting on MMIW cases

- Examples when MMIW cases are reported in the media…

-

-

- Reference to drugs or alcohol in articles about MMWI (38%)

- Reference to victims criminal history (31%)

- Reference to sex work (11%)

-

-

- Examples when MMIW cases are reported in the media…

Both violations of non-consensual and violent practices

Both lead to a formed narrative of violence back of the indigenous people/women

Yet both are still resistant fights that have lasted for centuries and continue to gain strength.

Keep on the fight.

Citations

Howard, Seánna, et al. “Indigenous Resistance to the Dakota Access Pipeline Criminalization of Dissent and Suppression of Protest.” The University of Arizona Rogers College of Law, 16 Mar. 2018, law.arizona.edu/sites/default/files/Indigenous%20Resistance%20to%20the%20Dakota%20Access%20Pipeline%20Criminalization%20of%20Dissent%20and%20Suppression%20of%20Protest.pdf.

MISSING AND MURDERED WOMEN & GIRLS. Urban Indian Health Institute, 2018, www.uihi.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Missing-and-Murdered-Indigenous-Women-and-Girls-Report.pdf.

“New Report on Murdered & Missing Indigenous Women & Girls.” Washington State Coalition Against Domestic Violence (WSCADV), 3 Jan. 2019, wscadv.org/news/uihi-mmiw-report/.

Schertow, John Ahni. “Colonialism, Genocide, and Gender Violence: Indigenous Women.” Intercontinental Cry, 17 Nov. 2007, intercontinentalcry.org/colonialism-genocide-and-gender-violence-indigenous-women/.

Toy, Adam. “’Labour of Love’ to Map North America’s Missing, Murdered Indigenous Women.” 770 CHQR, Global News, 23 Aug. 2018, globalnews.ca/news/4406277/labour-of-love-to-map-north-americas-missing-murdered-indigenous-women/.