Missing data obscures an invisible epidemic

“Data,” in this context, refers to human lives. The lost data facilitated by jurisdictional conflicts and lack of resources for tribal and local law enforcement carries the weight of lost human beings.

What data gap?

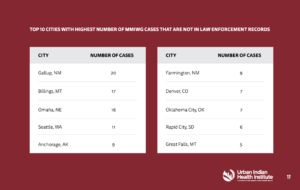

In 2016, 5712 cases of missing Native women were reported to the National Crime Information Center. Only 116 of these were recorded in the Department of Justice’s Missing Persons database. A 2018 report from the Urban Indian Health Institute discovered 506 cases and that 330 Native women had gone missing or been murdered since 2010- but 153 of these were absent from police records.

How does this happen?

Currently, no comprehensive, accessible, cross-jurisdictional database exists in which to record missing Native women. Since tribal, local, state, or federal law enforcement agencies may share jurisdiction, with a lack of collaboration and clarity, cases (women) are lost. Gaps of coverage exist due to databases not having ethnic options for Native women, jurisdictional battles when reservation residents are discovered or reported missing elsewhere, and tribal inability to prosecute violent crimes such as rape.

Is anything being done?

Savanna’s Act (examined further in “The History and Potential of Savanna’s Act” on this website), is federal legislature seeking to develop guidelines in response to cases of missing and murdered Native Americans and increase tribal enrollment for victims in federal databases. Several non-governmental organizations have also launched grassroots efforts to number and collect cases of missing Native women.

The Urban Indian Health Institute (UIHI) is an epidemiology center dedicated to strengthening the health of urban communities nationwide.

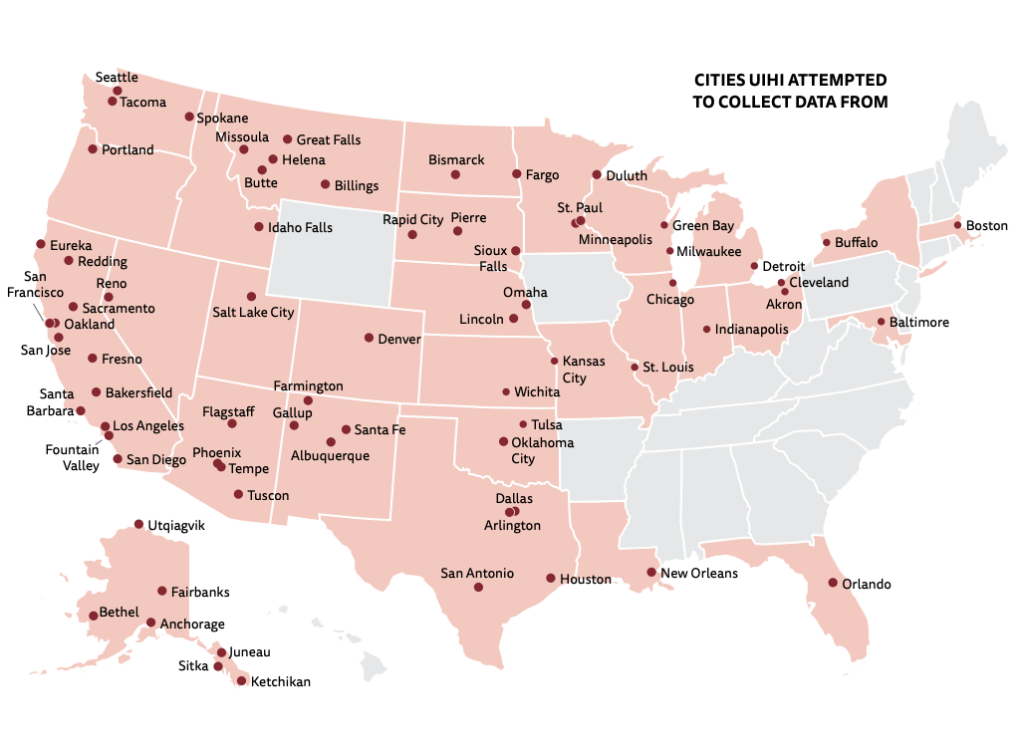

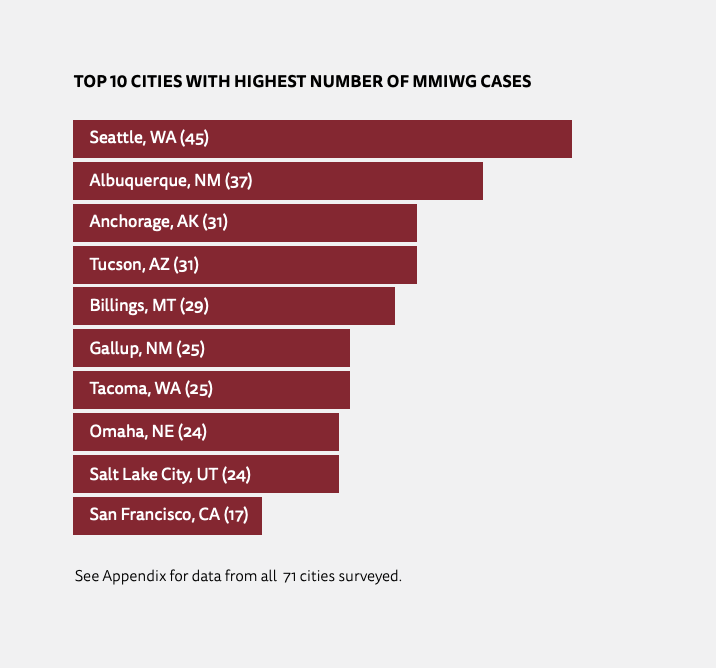

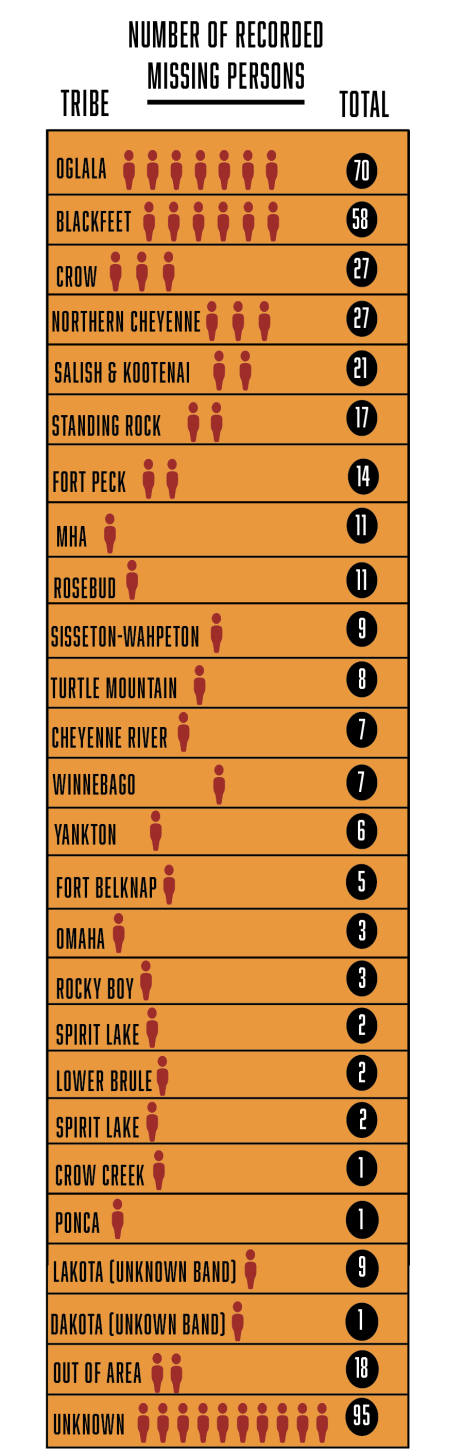

Though based in Seattle, Washington, the organization collects and compiles data, issues reports, and leads trainings on issues across the nation such as: HIV/AIDS, cancer, diabetes, and underaged substance use, amongst others. In 2018, the UIHI released a report intended to assess the difficulties of MMIW data collection, how law enforcement agencies track and respond to these cases, and the national narrative of the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women movement. Below are three images from the “Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls” report emphasizing the prevalence of this problem, and pervasiveness of the data gap.

The Sovereign Bodies Institute is a non-profit research center dedicated to research of gender and sexual violence against indigenous peoples.

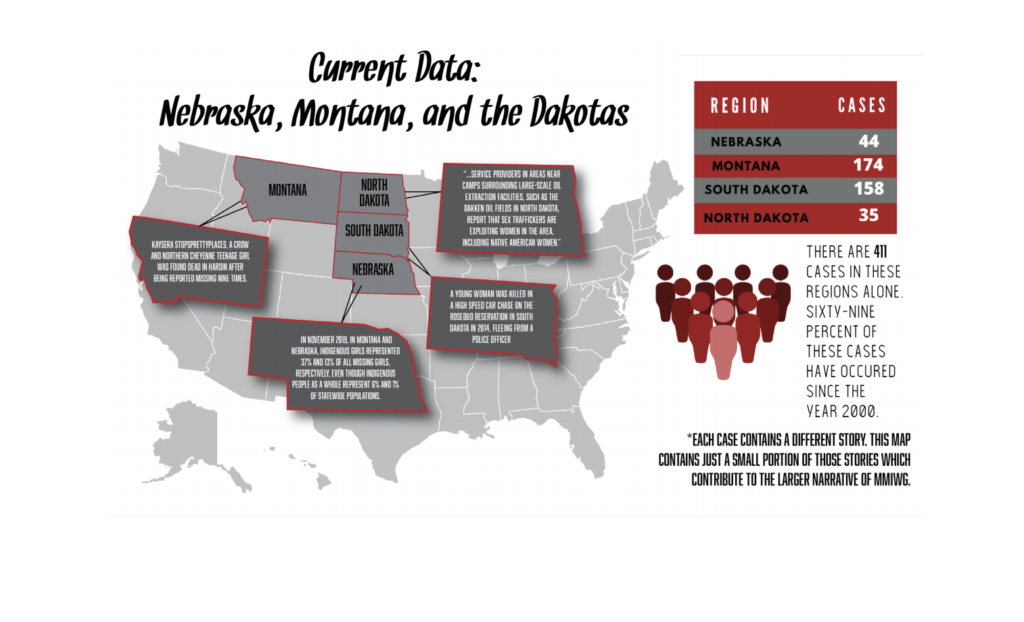

The Sovereign Bodies Institute (SBI) houses the MMIW database, one of the largest resources of its kind. The Sovereign Bodies Institute partners with tribal nations, scholars, and community organizations to conduct research which provides a deeper understanding of structures of gender and sexual violence against Indigenous people; in 2019 SBI published a deep dive report on MMIWG along the route of the Keystone Pipeline entitled “Zuya Winyan Wicayu’onihan” (Honoring Warrior Women). Below are a few key images from that report.

The Urban Indian Health Institute is a division of the Seattle Indian Health Board. Single, monthly, or annual donations to the Seattle Indian Health Board can be made through this page.

Urban Indian Health Institute. (2018). “Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls.” http://www.uihi.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Missing-and-Murdered-Indigenous-Women-and-Girls-Report.pdf

Urban Indian Health Institute. (2018). “Our Bodies, Our Stories: Key Statistics.” https://www.uihi.org/projects/our-bodies-our-stories/

Sovereign Bodies Institute. (2019) “Zuya Winyan Wicayu’onihan: Honoring Warrior Women” https://2a840442-f49a-45b0-b1a1-7531a7cd3d30.filesusr.com/ugd/6b33f7_27835308ecc84e5aae8ffbdb7f20403c.pdf

Hinojosa, Maria and Varela, Julio Ricardo. “The Stolen Sisters.” In The Thick, Futuro Media, 18 Sept.2018.https://www.stitcher.com/podcast/in-the-thick/e/56319840