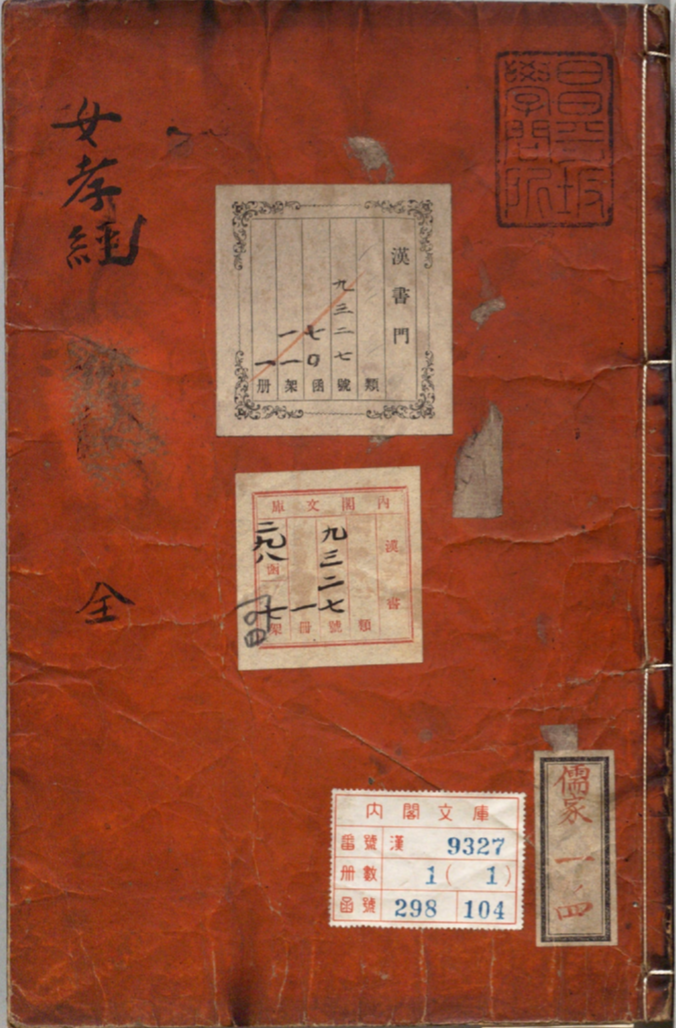

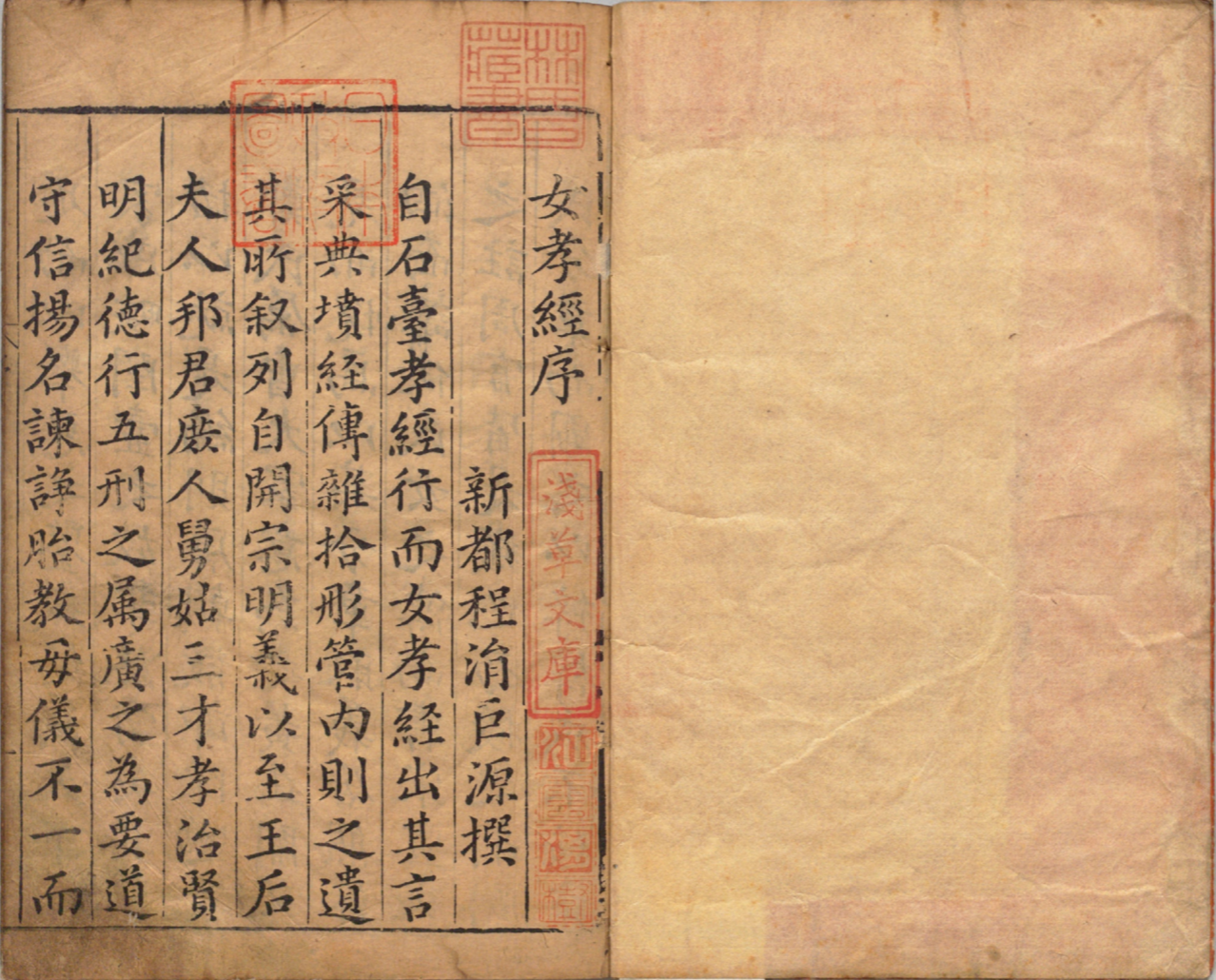

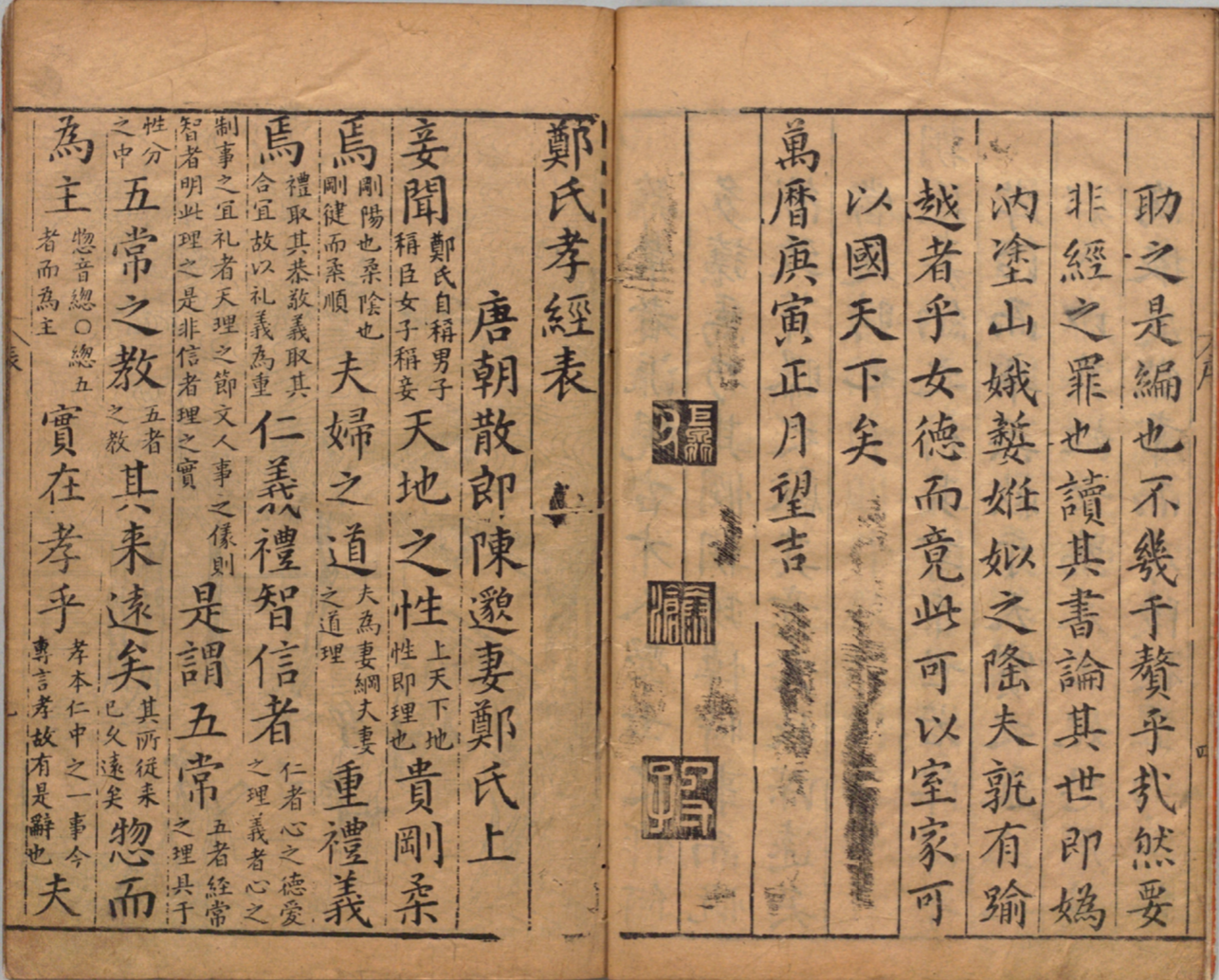

The Ladies’ Classic of Filial Piety (Nü Xiaojing女孝经) is a Confucian doctrine that prescribes a strict Confucian morality code of behavior for women. A counterpart to the Men’s Classic of Filial Piety (Xiaojing孝经), the text deals with propriety and filial piety as well as rules of behavior on the part of women. The author of the Ladies’ Classic of Filial Piety is a woman surnamed Zheng (郑氏) in the mid-Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE). Madame Zheng was the wife of a minor official, Houmochen Miao (侯莫陈邈) In the preface, entitled “Memorial on Submitting the Ladies’ Classic of Filial Piety,”[1] Madame Zheng stated that she wrote the Ladies’ Classic of Filial Piety to advise her niece, Consort Yong (永王妃) who would marry Prince Yong (a.k.a. Li Lin (ca.? -757).[2]). Madame Zheng explained her worries about the issues her niece would face when building a successful relationship with a newly married husband and his royal family. The Ladies’ Classic of Filial Piety originally contains eighteen chapters. It manifests filial piety as the supreme virtue required of everyone in society. According to Julia K. Murray, the Ladies’ Classic Filial Piety was based on the Admonitions for Women (Nu Ze女则), the Classic of Filial Piety (Xiao Ching孝经), and Lie Nu Zhuan (列女传) as they shared similar content, formats, narrative structure, and central figures.[3] Through comparing these prototypes with texts of the Ladies’ Classic of Filial Piety, it becomes clear that Madame Zheng cited numerous references to ancient classics and revealed her profound knowledge. In her preface and content of “Memorial on Submitting the Ladies’ Classic of Filial Piety,” she also used extensive quotations from the ancient literature, such as the Book of Rite (Liji), YiJjing, and Confucian Analects (Lunyu). Unlike the clarity of the content prototype, the authorship of the Ladies’ Classic Filial Piety is murky. It was first mentioned in the thirteenth-century History of Song Dynasty, but the biography of the author Madame Zheng was minimal regardless of the fact that she may be the first author to have directly proposed that women’s moral power was comparable to men’s. Some scholars question Madam Zheng’s gender and make a hypothesis that the real author was a man who assumed female authorship to educate women more effectively, but this assumption cannot be verified by concrete evidence.

The visualization of the Ladies’ Classic of Filial Piety has a rich history. [4]Records of paintings related to the Ladies’ Classic of Filial Piety can be found in the inventories of the calligraphy and painting in the imperial collection of the Song dynasty; other references of the Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties are also present. The twelfth-century The Xuanhe Catalogue of Paintings (Xuanhe Huapu) mentioned that there were five different versions of the Ladies’ Classic Filial Piety illustrations[5], including the two existing handscrolls (collected in Taibei National Palace Museum and Beijing Palace Museum [hereafter the Beijing scroll]). Taibei scroll originally was one of a pair, but only the first nine chapters survived. It begins with the inscription, followed by a chapter text and its illustration, and this alternation is maintained throughout. The inscription was written by the Southern Song emperor Gaozong (1107-1187), and his court artist Ma Hezhi (ca.1130-1170) completed the paintings. The Beijing scroll is in a slightly different order. It begins with a painting, followed by the inscribed chapter, and kept the pattern in all nine chapters of the scroll. [6]

The Beijing scroll and Taibei scroll not only vary considerably in the order of chapters and in the matching of inscriptions and paintings but also differ in style and composition. The objective description and emotional detachment of the Beijing scroll suggest a late Tang prototype. Firstly, the setting of space was relatively simple comparing with intricate compositions in the Taibei scroll, and the outdoor scenes were merely defined by a tree and rock, leaving blank silk to imply the ground. The voluptuous treatment of the large and substantial female forms also evoked the legacy of Tang painters such as Zhang Xuan (731-755) and Zhou Fang (730-880). The figures were contoured with even, unobtrusive brush lines, which were filled in with opaque mineral pigments, and ornate designs were depicted in the garment fabrics. The idiosyncrasy of women dressing in male costume reflected a fashion among Tang court women not found in the Taibei scroll. However, the landscapes painted on large standing screens in several of the scenes illustrated the style of Southern Song landscape painting and implied that the date of Beijing scroll could not be earlier than the thirteenth century, but it is uncertain which of the two scrolls came first. Since the Beijing scroll carries more reference to the archaic Tang style, the time when the Ladies’ Classic of Filial Piety was written, this website uses it as our primary work. [7]

Each section of the Beijing scroll depicts aristocratic figures in the garden, dew platform, architecture, and landscape as the background. Settings of scenes also include furnishings, textiles, utensils, and plants. The missing of the artist’s signature, which was common among court painters in premodern China, the exquisite brushwork, and the popularity of didactic painting in the Southern Song court suggests that this painting was likely an imperial commission for the court ladies. The various seals of private and imperial collectors help reconstruct the painting’s trajectory prior to the modern time. The seal of “ Caorong Miwan” (曹溶密玩) from the connoisseur, Cao Rong (1613-1685), shows that it had once left the Song court and became a connoisseur’s collectable in the seventeenth century before returning to the imperial collection a century later, which is proved by the imperial seals of three Qing emperors of Qianlong, Jiaqing and Daoguang.

[1] Hao, Dong. The Complete Literary Works of the Tang Period (钦定全唐文). Taibei: Hongwen Public House, 1961, 945.

[2] Li Lin’s biography appeared in Ou Yangxiu’s The History of Song and The New History of Tang. Beijing: Zong Hua Shuju, 1975, 82.

[3] Murray, Julia K. “Didactic Art for Women: The Ladies’ Classic of Filial Piety” In Flowering in the shadows: women in the history of Chinese and Japanese painting, edited by Marsha Smith. Weidner. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1990, 27-53.

[4] The reasons why women’s didactic painting reached its peak in the Song Dynasty were related to the change of regime, the refinement of painting classification, and the ranking of painting types. At the beginning of Song Dynasty, Emperor Taizu (Zhao Kuangyin, 927-976), inherited the principle of “ruling the world with filial piety” since the Han Dynasty, and not only reintegrated the Confucian filial piety into the political rule also selected officials based on their filial piety, a. After experiencing the turbulence of the Five Dynasties and the Ten Kingdoms (907-960) in the late Tang, the rulers of the Song Dynasty aimed to use the Confucian ideology as a weapon binds the country together. In the Southern Song Dynasty, the emergence of a large number of works of art with female subject was closely related to the political crisis at that time. After Song Gaozong escaped from the current imprisonment of the Jin Dynasty (1115-1234), he established a new capital in Nanjing in 1127. Hence a major challenge emperor Gaozong faced was to prove the legitimacy of his regime. Therefore, he strongly advocated Confucianism and produced a large number of propaganda and educational paintings through official workshops with obvious political intentions.

[5] There are another three other scrolls share a lot in common with Beijing scroll. They depict the first nine chapters of the Ladies’ Classic of Filial Piety, the same chapters are included in the Beijing Scroll. Photographs of two of these scrolls were published in the early twentieth century, but the whereabouts of the scrolls themselves were not currently known. One was attributed to Zhao Boju (act first half of the twelfth century) with the inscription written by Song Huizong (1082-1135). This scroll was photographed in 1913 when it was in the collection of Chen Kuiling (1855-1915). Another scroll was attributed to Chen Juzhong (act. early thirteenth century), belonged to Mr. Ren in Shaoxing (绍兴任氏) when it was published in 1931. Its calligraphy sections were not reproduced or described. The last scroll was attributed to Yan Liben (601-673) and calligraphy to Yu Shinan (558-638). It was described with great detail by Wu Sheng’s (Qing Dynasty) Da Guanlü (大观录 1712), enabling us to study it even though the scroll itself has disappeared. Wu noted that the calligraphy on paper looked more like the style of Southern Song emperor Gaozong (1107-1187).

[6] Julia Murray gave a detailed comparison between the two scrolls relying on the evidence from the illustrations and texts themselves. In the content, two existing handscrolls had same first nine chapters, which are “The Starting Point and Basic Principles,” “Empress and Imperial Consorts,” “Noble Ladies,” “Wives of Feudal Lords,” “Common People,” “Serving the Parents-in-law,” “The Three Powers,” “Government by Filiality,” “Elucidating Wisdom” respectively. The chapters of Ladies’ Classic of Filial Piety started from the form of a dialogue between the famous female master Ban Zhao (ca.45-117) as a teacher and a group of young ladies as her students. Thus, the central character of the first chapter “The Starting Point and Basic Principles,” was Ban Zhao. In addition to chapter four “Elucidating Wisdom “has a clear heroine was Fan Ji, female characters are all anonymous court or noblewomen in other illustrations of chapters.

[7]The Scholar, Mu Yiqin, from the Beijing Palace Museum stated that the painter of the Beijing version is anonymous in the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127) according to the figures’ hairstyles, clothes, and the setting of furnishings. Mu Yiqin assumed the period of the scroll is approximate during the Northern Song Dynasty, whereas other connoisseurs recognized the date of scroll according to the feature of the brushwork that is “axes-cut strokes”. The painters of the Southern Song Dynasty used “axes-cut strokes” in the ink landscape paintings to depict the hard and angular texture of rocks and trees.