A comparison with other portrayals of Ban Zhao and Fan Ji poses an interesting question about the changing expectation on women in pre-modern China. Fan Ji had been featured in the fourth-century painter Gu Kaizhi’s (ca.345-406) Admonitions of the Instructress to the Court Ladies (Nüshi zhen tu). Unlike Madame Zheng, the painter depicted another story about Fan Ji’s success in dissuading the King from indulging in hunting. Here, only the imperial couples are painted, but Fan Ji stands upright and her stern gaze confronts the King’s. The dynamics is a stark contrast to the portrayal in the Beijing scroll and is thus a testimony of how much more suppression had put on women’s shoulders since Gu’s time (Fig. 5.3).

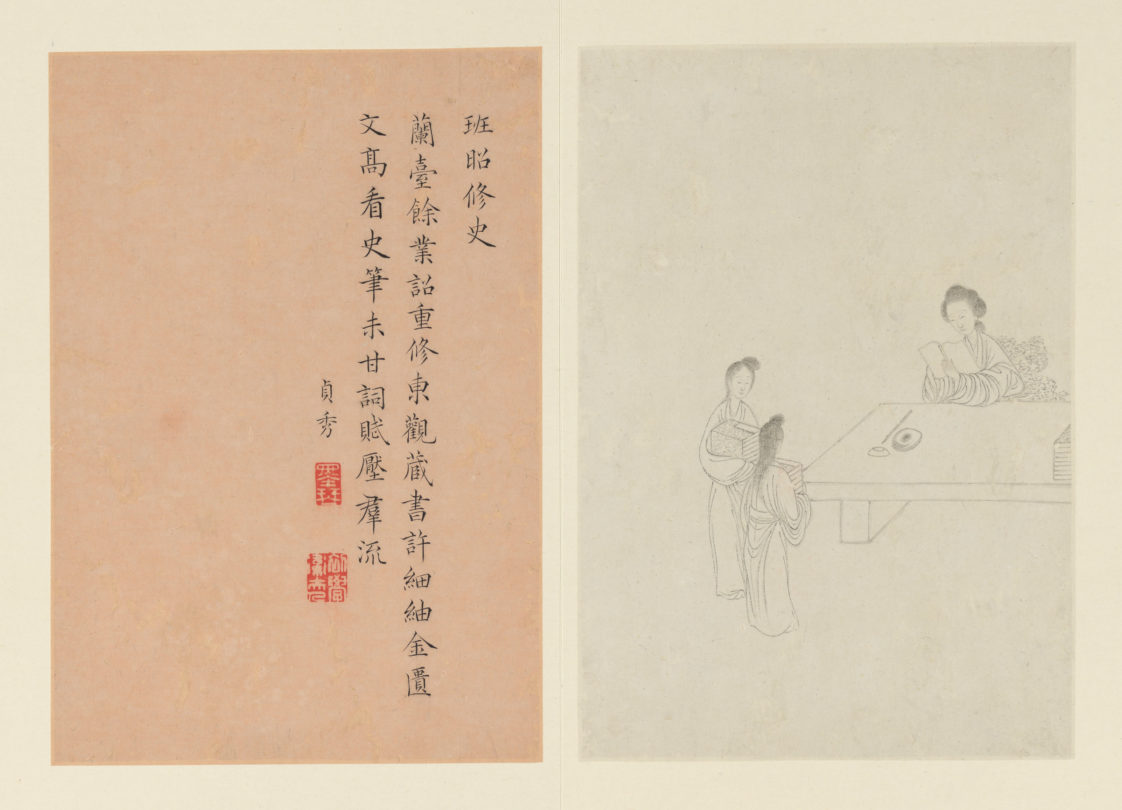

Such emphasis on model women’s subjectivity and intellectual property reemerged after the Confucian social orders began to loosen in the nineteenth century. The illustration of Ban Zhao commissioned by a woman scholar is especially noteworthy. In 1799, Madame Cao Zhenxiu (1762-1822) wrote a series of sixteen poems about famous women in history, including Ban Zhao, to express her admiration for women’s talent in literature. Cao commissioned Gai Qi (1773-1828) to illustrate her poems. The painter, possibly instructed by the patroness, depicted Ban Zhao reading before the desk. This scene alludes to Ban’s achievement in historical literature. She read tirelessly over the years and re-organized and revised the scattered chapters left by her father and brother to finally add eight chapters based on the manuscript and completed the History of the Former Han. Her isolation is the opposite to the group figure in the Beijing scroll, and this different rendition is anything but random. After all, Ban Zhao also authored the Admonitions for Women that later became the source of Confucian discourse on women’s subjugation. By avoiding the portrayal of her teaching other women, the painter uplifted his patroness’s intention of addressing Ban Zhao’s scholarly contribution (Fig. 5.4).