The saying, “men till, women weave” (nangeng nüzhi男耕女织) describes the gender division of labor in premodern China. “Weaving” that represented women’s productive work has gone through a conceptional change. In the early text, “weaving” was a synecdoche for the whole process of textile production, but the “womanly work (nügon女功)” that developed afterward referred to as a combination of sericulture and textiles weaving and clothes making. In the Confucian discourse, womanly work was a universal virtue for women of all strata in society, but its economic importance should not be overlooked, either. During the Song dynasty, government taxation appeared in two forms: grain and fabric. Every rural family needed to submit both, and most of the fabrics were supplied by peasants and manors. Fabric production in the village was basically done by women.[1] The clothing also has monetary worth because cloth is a medium of exchange and a standard currency, so womanly work was valuable labor that brought income to the household. No wonder the Book of Rite recorded that “the wife is the fitting partner of her husband, performing all work with silk and hemp” to suggest a relatively equal dynamics between the labors of men and women.

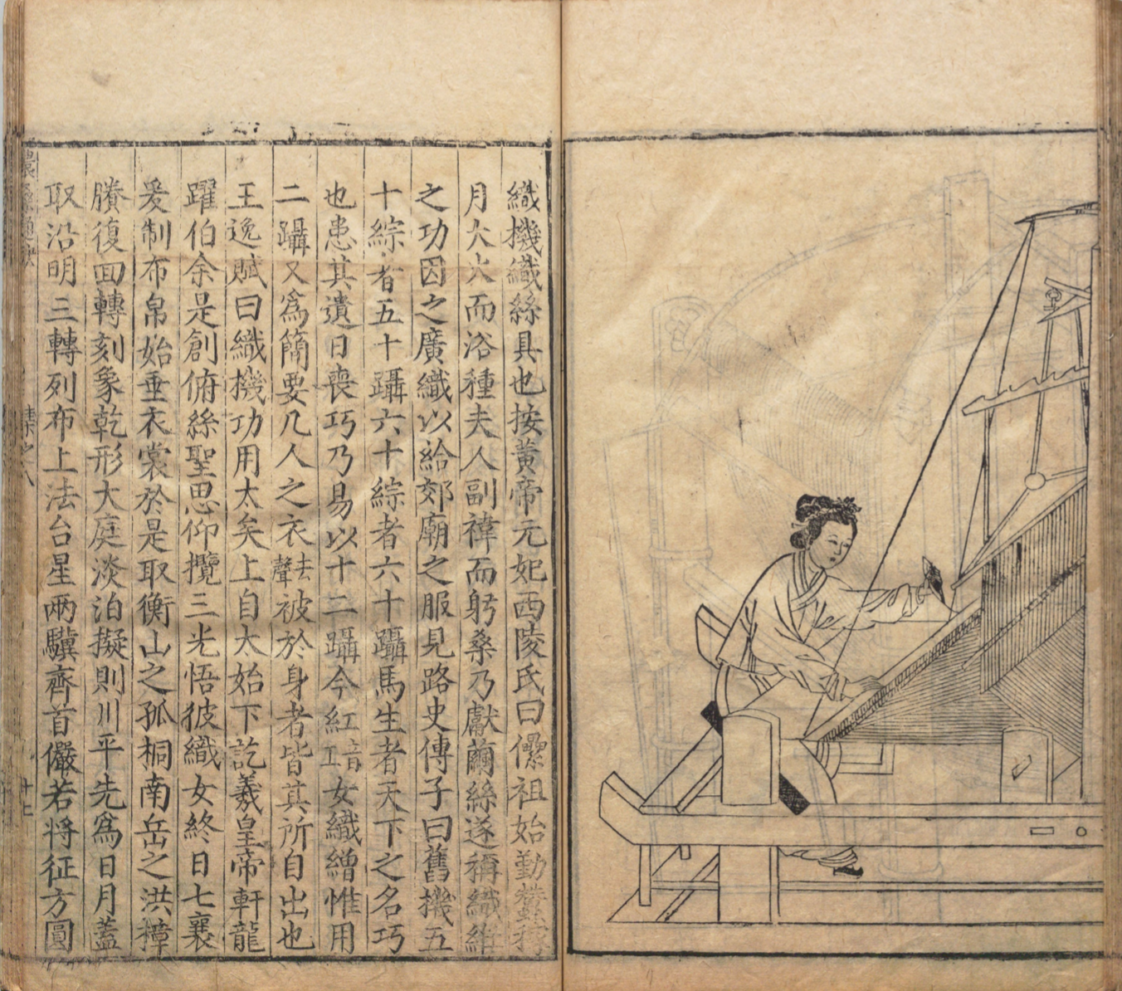

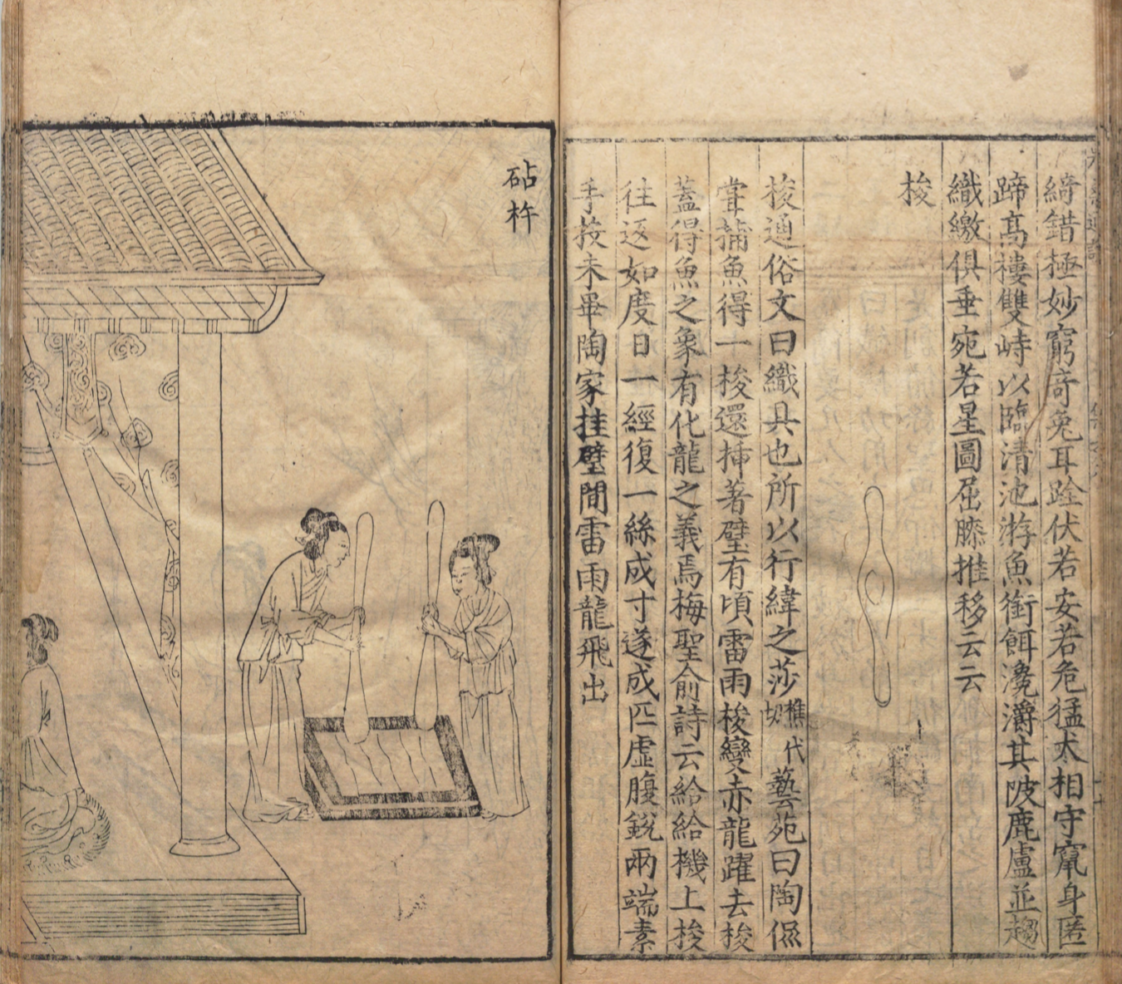

As practical as it was, textile production is also colored by symbolism. Confucian classics such as Rite of Zhou, Book of Rites, recorded the ritual held in the spring to celebrate the beginning of the sericulture season. “Sacrifices” in the Book of Rites explained in detail the gender division of this ritual, during which the empress raised silkworms to provide sacrificial costumes in the northern suburbs while the emperor cultivated the land to provide sacrificial offerings in the southern suburbs. The purpose of the ritual was to express the sincerity and piety of serving the gods. The ceremony of textiles provided fundamental metaphors of rule and social order. Furthermore, womanly work is considered a necessary means to cultivating women’s virtues of diligence, frugality, order, and self-discipline. Little girls were taught spinning and weaving to learn respect for the hard work and weave hemp to learn frugality and diligence. Womanly work reflected the hierarchy in the inner quarter too. The wife was in charge of the workforce of women in the household including concubines, servants, or hired weaving women to do the work.

Chapter Nine, “Common People” stresses that women should diligently focus on the work of sericulture and textile weaving in the domestic sphere and take care of their parents-in-law rather than interfere with the outside world. The illustration of the chapter depicts five court ladies. Four women sit on the mats and rugs on the ground while one stood behind the table on the left. These images of ladies are based on the characteristics of beauty paintings of the Tang dynasty. The painter used continuous and smooth lines to render the women with graceful and elegant faces and bodies. Their clothes are elegant green and white soft silk, suggesting that their prominent social status rather than meager rural women. The ancient bronze ware placed on a high table shows the elegant taste of these women. These ladies are placed in the empty background to shape the isolated and private female space (Fig. 3.1). Understandably, the illustration does not follow the text as closely because the purpose of this scene is to give the emperor’s empress and concubines idealized moral models.

Womanly work was significant for women, their family, and the country. First, women as labor create economic value. Second, rituals related to woman’s work represented the symbolic significance for rulers. Third, working on sericulture and textiles cultivated female personal virtue. The government encourages to create a large number of works of art about womanly work and widely disseminate because of the government’s encouragement to the textile industry, the state’s tax policy, the imperial court’s advocacy of Confucian ethics, and the strengthening of political propaganda function of court paintings. Moreover, the viewers, on the one hand, could learn how that court ladies cultivated their own morality through textiles, and on the other hand, could view that the beautiful costumes ladies wore and perceive the ideal results achieved by this moral cultivation.

[1] Wu, Hung. Feminine space in Chinese painting. Beijing: san lian shu dian, 2019, 247-249.