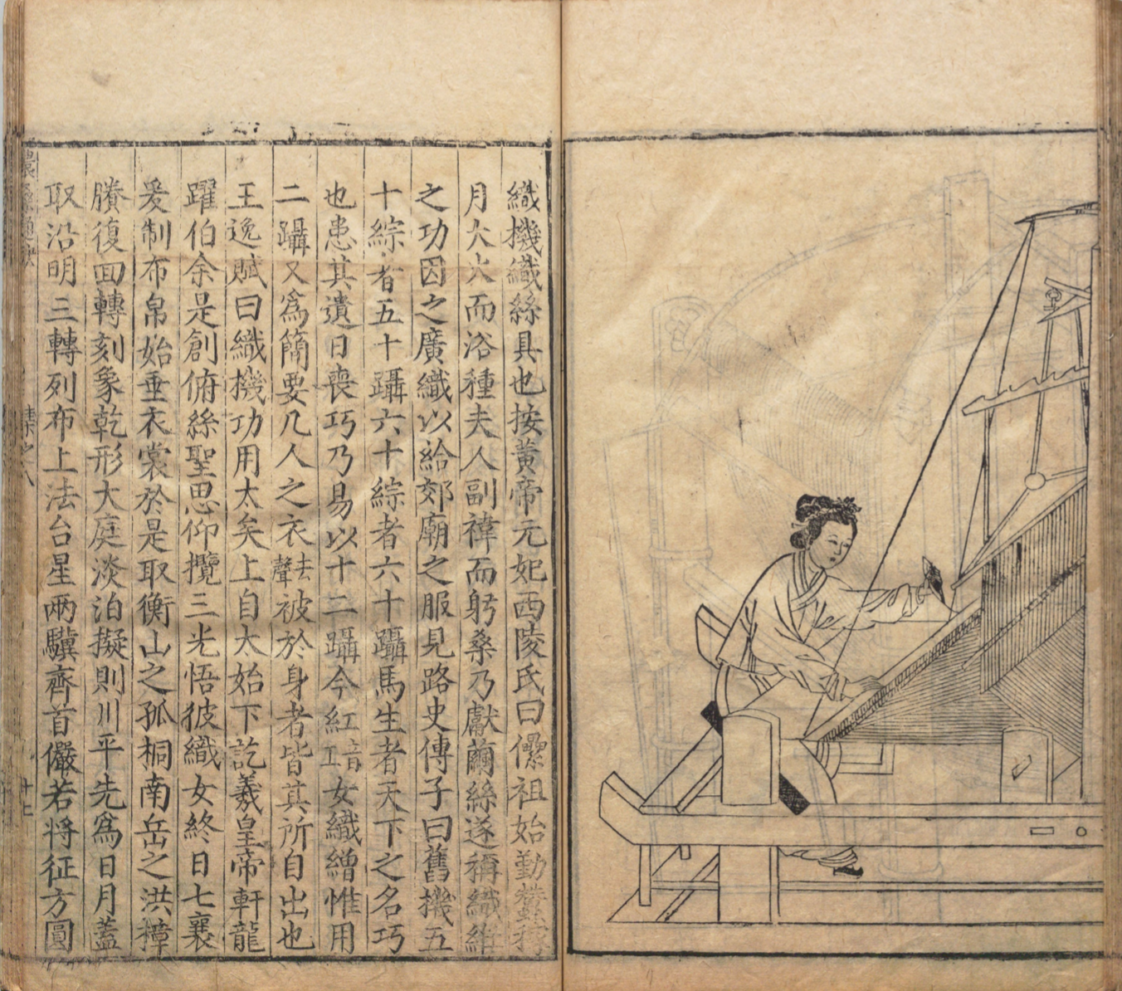

The saying, “men till, women weave” (nangeng nüzhi男耕女织) described the gender division of labor. Men worked on plant food grains in the outdoor farmland, while women produced fabric in the domestic quarter. They were thought of as equally productive labor of the family. In the early text, “weaving” was a synecdoche for the whole process of textile production. Later, the concepts of “womenly work (nügon女功)” referred to making clothing from the process of sericulture and textiles. The process of producing textiles included spinning, weaving, tailoring, sewing, and embroidery. The women were originally responsible for the whole process. Womanly work was the responsibility of all women, from royal and aristocratic women to rural women. “Wedding” in the Book of Rites stated that the wife’s responsibility was to work on fabric production.[1] In the text of Chapter Five: “Common People” are translated below. “In carrying out the way of the wife, understand the benefits of righteousness. Put others first and oneself last, thereby serving your parents-in-law. Spin thread, make garments, and supply the sacrificial foods for the altars. This is the filiality of the wife of a commoner. The Classic of Poetry says, ‘A woman who has nothing to do with public affairs / Leaves her silkworms and weaving.’ It means that the duty of women should diligently focus on the work of sericulture and textiles at the inner sphere and take care of the parents-in-law rather than interfere with the outside work.

In the Song Dynasty economic system, government taxation came from two forms: grain and fabric. Every rural family needs to pay both, and most of the fabric was supplied by peasants and manors. Fabric production in the village was basically done by women.[2] The clothing also has monetary worth because cloth is a medium of exchange and a standard currency so that womenly work could add greatly to the wealth of a household. The Book of rite recorded “the wife is the fitting partner of her husband, performing all work with silk and hemp.” Therefore, female contribution helps the subsistence products and household economy, and men and women are equal contributors to the tax payments to realize responsibilities toward the state.

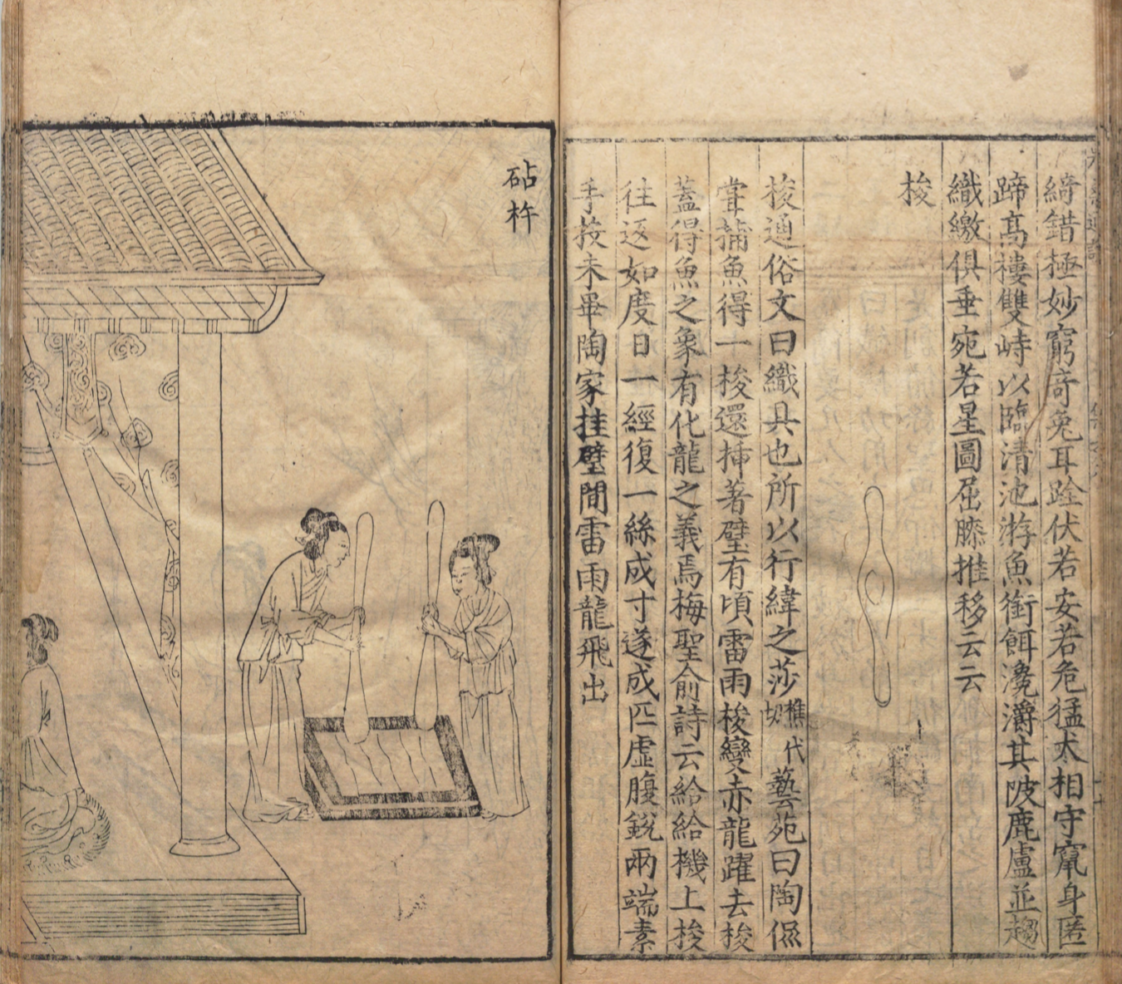

Furthermore, textile production is related to etiquette activities. Confucian classics such as Zhou Li, Book of Rites, recorded a feminine ritual held in the spring to celebrate the beginning of the sericulture season. “Sacrifices” in the Book of Rites explained in detail the gender division of this ritual. The sacrifice must be attended by the couple themselves. Therefore, the emperor cultivated the land to provide sacrificial offerings in the southern suburbs, and the empresses raised silkworms to provide sacrificial costumes in the northern suburbs. The purpose of the ritual was to express the sincerity and piety of serving the gods. The ceremony of textiles provided fundamental metaphors of rule and social order.

What’s more, Womenly work is considered to be a necessary means to cultivate women’s virtues of diligence, frugality, order, and self-discipline. In the hierarchy society, Patriarchs require little girls to learn spin and weave in order to learn respect for the hard work of their inferiors and weave hemp to learn frugality and diligent. By fabric production, aristocratic women produced the moral value of personal such as “chastity” and “filial piety”. Womenly work shows the ranking in the inner sphere too. The wife governed the workforce of household women and the concubines, servants, or hired weaving women give the craft. In this case, Women need to perform the work to accomplish female morality.

[1] Bray, Francesca. “Fabric of Power: The Canonical Meanings of Women’s Work,” in Technology and Gender Fabrics of Power in Late Imperial China. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997,182-191.

[2] Wu, Hung. Feminine space in Chinese painting. Beijing: san lian shu dian, 2019, 247-249.