Below are links to learn more about the history of the Chagossian exile and the base on Diego Garcia. (Inclusion here does not mean endorsement by The Chagos Archive.) A brief historical overview is at the bottom of the page and a timeline is here. An excellent resource for learning more is “The Chagos Archipelago” website by Dr. Richard Dunne. To suggest the addition of a website, article, book, film, or other work, please email chagosarchive@gmail.com.

Articles & Books

Film & Video

Exiled from Diego Garcia: The Chagossians & an Anglo-American Base

Around the end of the American Revolution and the close of the 18th century, enslaved peoples from Africa became the first settlers in the Indian Ocean’s Chagos Archipelago, when they were brought to work on the archipelago’s largest island, Diego Garcia. Followed by their free descendants and indentured laborers from India, a diverse mixture of peoples, religions, and traditions merged to create a unique society in Chagos. Today, the only people living in Chagos are soldiers and civilian contractors working on the billion-dollar U.S. military base on Diego Garcia. Between 1965 and 1973, the U.S. and U.K. governments forcibly removed the inhabitants of Chagos to create the military base. The people, known as Chagossians, were left in impoverished exile on the western Indian Ocean islands of Mauritius and the Seychelles.

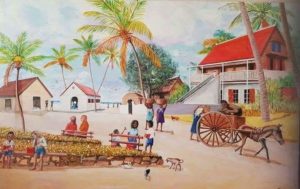

In a setting of idyllic white sand beaches and fertile green vegetation, the ancestors of today’s Chagossians built a society that by the 20th century included numerous villages complete with hospitals, roads, churches, and schools. The people began to speak their own language, Chagos Creole. The population grew to 1,000-2,000 people. Life was not luxurious, but in exchange for their labor on Chagos’s coconut plantations, Chagossians enjoyed guaranteed employment, regular salaries in cash and food, free housing and land for gardens and animals, health care, vacations, pensions, schooling, and free access to Chagos’s fishing grounds and flora. Life was peaceful. Poverty was unknown. Chagossians enjoyed good health.

In the 1960s, this life transformed. The U.S. administrations of Presidents Kennedy and Johnson convinced the British government to detach the Chagos Archipelago from colonial Mauritius to create a new colony solely for military use, called the British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT). As part of a confidential 1966 agreement, U.S. officials ordered the removal of the entire population. The U.S. Government secretly transferred $14 million to the British government to create the BIOT and remove the Chagossians. Military and other high-ranking Anglo-American officials kept the deal from Congress, Parliament, the UN, the media, and the public. Officials agreed that, if asked, they would “maintain the fiction” that the Chagossians were transient laborers rather than a people with ancestry in the islands dating back generations.

Beginning in 1968, any Chagossians leaving Chagos for vacations or medical treatment were denied their customary return passage home and left stranded in Mauritius. This typically left them separated from family members and most of their possessions. At the turn of the decade, the British began restricting the number of regular supply ships visiting Chagos, leading more Chagossians to leave as food, medicines, and other necessities dwindled.

In 1971, officials of the British Government, acting on U.S. orders and with some assistance from U.S. soldiers, forced the remaining inhabitants of Diego Garcia to board overcrowded cargo ships and leave their homes forever. The ships dumped some of the Chagossians 150 miles away in Chagos’s far-off Peros Banhos and Salomon islands and others 1,200 miles away on the docks of Mauritius and the Seychelles. In the process, British government agents and U.S. Navy Seabees first shot, then poisoned, and finally gassed and burnt the islanders’ pet dogs in sealed sheds. By 1973, the Chagos Archipelago had no more permanent inhabitants as the last Chagossians were deported to Mauritius and the Seychelles.

In Mauritius and the Seychelles, the Chagossians received no resettlement assistance and quickly found themselves living in what the Washington Post called “abject poverty.” To this day, Chagossians living in Mauritius and the Seychelles face impoverishment and unemployment. Many live in homes of corrugated metal and wood with poor or nonexistent water and sanitation services. Many suffer from poor health and low levels of education. Many have been the victims of ethnic discrimination from Mauritians and Seychellois, and many have suffered through other forms of daily harm and humiliation accompanying life as a marginalized underclass in exile. In their own words, their life is one of sagren—the grief of being exiled from their natal lands—and lamizer—a miserable, abject poverty beyond that of low incomes alone.

From the moment Chagossians were deported, many demanded to be returned to Chagos or to be properly resettled. In the 1970s and 1980s, many suffered through hunger strikes and arrest to win small compensation payments from the British government. The money totaled around $6,000 per person. For most, it was only enough to pay off substantial debts incurred since the expulsion or to get what for many was their first formal home in the slums of the Mauritian capitol, Port Louis. Chagossians in the Seychelles received nothing at all.

The Chagossian struggle began to gain international attention through a series of court cases, beginning in 1997, when the Chagos Refugees Group launched a lawsuit against the U.K. In November 2000, Chagossians were victorious: The British High Court ruled the Chagossians’ removal illegal. Twice more, the people would defeat the British government in the High Court. On the government’s final appeal, Britain’s then highest court, the House of Lords, upheld the Chagossians’ exile in a 3-2 decision. The ruling effectively reaffirmed colonial law, concluding that the government’s military and financial interests trumped the Chagossians’ right to live in their homeland. An appeal to the European Court of Human Rights was dismissed. A class action lawsuit filed against the U.S. Government and several Government officials was similarly dismissed.

Despite the setbacks, Chagossians have continued their struggle. In January 2015, the British government’s own study found that it was feasible for Chagossians to resettle their islands (U.S. military personnel have lived there for nearly five decades and Chagossians’ ancestors had lived there for generations). Despite the finding, the government deliberated until deciding in 2016 that it would not allow a return, instead offering £40 million in unspecified programs over 10 years to improve Chagossians’ living conditions.

In 2018, Chagossians will return to court in three cases: 1) A challenge to the 2016 decision to bar resettlement despite the feasibility study; 2) Chagossians in Seychelles suing for compensation given that they received none of the small sums paid in the 1970s and 1980s; and 3) a challenge to the British government’s unilateral declaration of a Marine Protected Area (MPA) in the Chagos Archipelago. This last suit follows a UN court’s ruling that the U.K. government acted illegally in creating the MPA and revelations from a State Department cable, originally released by Wikileaks, showing that the U.S. and Britain saw the MPA as the best way to prevent Chagossians from ever returning home.