Strategy 1 Nutrition Education and Motivational Interviewing

Strategy 2 University of Minnesota Extension program

Strategy 3 Social Cognitive Theory

Strategy 4. Social Media

Strategy #1

Below is an outline of some of the science theories I will use in my program. They have been my influence to design a program that will be effective for teens to help them change behaviors. Adolescent years are formative years. Social Cognitive theory is very effective for teenagers and behavior change. (Bagherniya, et. al., 2018) In addition, I think SCT is the best tool for increasing self-efficacy of teens. Healthy teens is a program that uses self-efficacy at the core of its program and therefore the use of SCT, social learning from peers and role models on social media is the best and most effective way to enhance behavior change in a positive way.

Summary of Theories and Strategies

Activity: Motivational Interviewing

Strategy: Find out current needs and attitudes towards change. Strategy – Motivational Interviews

We will recruit 30 teenagers from Mercer Island High Schools ages 15-19. They will be made up of 50% girls and 50% boys. We will conduct Motivational Interviews with each teenager in a confidential setting. Our staff will be trained on proper guidelines and how to conduct a motivational interview. We will have paper questionnaires and teenagers can write in answers or have you record if they prefer. Dose delivered will be 30 participants. Dose received is 30 participants. Reach is 30 participants.

Questions will include:

- What are your health goals?

- Do you exercise and if so, how often?

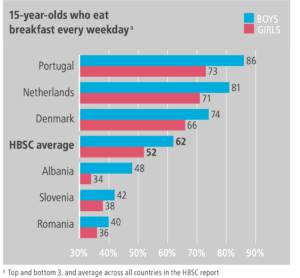

- Do you eat breakfast and how many days a week?

- Do you feel breakfast is important?

- Do you skip meals – if so, which ones regularly

- Do you eat fast food? How often

- Do you drink soda? How often

- Are you interested in learning about becoming healthier and stronger?

Impact:

As mentioned above, Motivational interviewing is person centered and will allow me to “explore” my teens health issues and eating habits and design a need-based approach. MI allows teenagers to “explore and resolve ambivalence associated with behavior change (Rubak et. al., 2005). The impact is the ability to resolve ambivalence with MI.

Strategy #2

Minnesota Extension Program

According to the search institute (2017) literature, eight elements of best practices from the University of Minnesota Extension that are proven to work for youth development will be included in my program. They are:

- Youth feel physically and emotionally safe

- Youth experience belonging and ownership

- Youth develop self-worth

- Youth discover self

- Youth develop quality relationships with peers and adults

- Youth discuss conflicting values and form their own

- Youth feel the pride and accountability that comes with mastery

Strategy: Social Cognitive Theory: Strategy #3

SCT

My team of 20 volunteers will work with teenagers who attended the workshop. We will send out worksheets to track fast food and soda intake for 4 weeks after workshop. We will also track dieting behavior. We will create data to figure out post workshop impact of study.

Dose up to 1500 teens

Reach up to 1500 teens

Impact : Bandura’s SCT is a main component of addiction quitting (Heydari et. al., 2014). The teens in my workshop will keep records of their fast food and soda intake for one month. The boys will gain control over their behavior and learn self-regulation and self-control that will have a large influence on the impact of my study (McKenzi et. al.,2017, p. 177). The impact is behavior change.

Strategy #4

Activity: Social Media Campaign

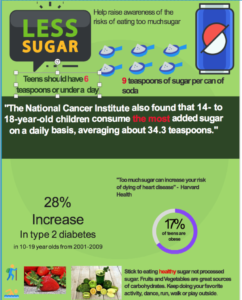

Why is social media important? In my three years at American University, I have studied cases of teenagers and the influence social media has on their behavior. I have done several presentations on body image and teenagers and know that social media and role models are very useful in helping change negative behaviors. My goal is to develop a social media campaign aimed at reducing fast food and sugar intake using a celebrity athlete as a role model. I previously designed this infographic that will be distributed to teens.

Strategy: Use Social Media campaign for one month in conjunction with zoom workshops to change awareness and behavior. Strategy

Social Media / Zoom Workshop

I will conduct a series of three, one hour workshops myself on zoom. I will have two assistants to help me gather questions and set up the zoom workshop. I will also have my assistants make sure an invitation to the workshop is accepted by participants. The workshop will be open to all teens on Mercer Island ages 15-19 years old. Dose is one workshop. Dose delivered is 3 times one 60-minute workshop. Reach is approximately 1500 teens at Mercer Island High School.

Social Media Impact: As mentioned above, since teenagers are very active on Social Media, I know this is an effective way to connect and communicate with this age group. The advantage of social networking is that they can easily invite friends, I can reach a lot of people, I can update and post information quickly and there is unlimited space (McKenzi et. al., 2017, p. 214). Social media has some unique qualities such as it is user generated, it is low cost, information can be revised quickly and it can reach more people (McKenzi et. al., 2017, p. 199). The impact will be gaining knowledge of healthy eating and dieting concerns to health in the teenager population.

Activity:Tracking soda and fast food during and after study

Strategy: Change through awareness of current behaviors.

Questionnaire

My team of 20 volunteers will work with teenagers who attended the workshop. We will send out worksheets to track fast food and soda intake. We will also track dieting behavior. We will create data to figure out how pre-workshop eating and dietary behavior. Dose and reach up to 1500 participants.

Step 3-5

| Target of Question | Process- Evaluation Question | Method of Assessment for Question | Resources Required |

| Recruitment | Were teens aware of the program? | *Did our pre-diagnostic questions help us find the appropriate data? | *Did we have enough volunteers? |

| Reach | Did we have enough resources to reach 1500 teenagers? | Did we sign up 60% teenagers for our workshop? | *Did we overextend our volunteers? |

| Fidelity | Did our logic model fit the program adequately? | Did this age group participate in the survey? | *Did our volunteers learn how to conduct Motivational Interviews properly? |

| Context | Did social media platform fit the program? | Did social media work as a way to deliver our workshop? | Did we have a clean workshop on Zoom ? |

| Dose Delivered | Did we have enough Motivational Interviews? | Did we deliver all of the questionnaires ? | Did we have a lot of participants? |

| Dose Received | Did we get back enough questionnaires before and after the workshop? | *Was our self-assessment and data returned after the workshop ? | Did it seem to be well received by participants ? |

Step 6

I think the most important questions are:

did we have enough volunteers, or did we overextend them?

did they learn how to interview using the process of motivational interviewing. My reason these are most important is because motivational interviewing takes a skill set and when performed improperly may not provide the needed information. In addition, I feel it is important to credibility and long-term use of our programs to do the program properly and to make sure we are not short staffed to get the program done well.

Reference:

CDC’S GUIDE TO. (2020). Retrieved from

https://www.cdc.gov/socialmedia/tools/guidelines/pdf/guidetowritingforsocialmedia.pdf

Healthy Eating During Adolescence. (2020). Retrieved April 1, 2021, from

https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/wellness-and-prevention/healthy-eating-

Heydari, A., Dashtgard, A., & Moghadam, Z. E. (2014, January). The effect of Bandura’s social

cognitive theory implementation on addiction quitting of clients referred to addiction

quitting clinics. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3917180/

McDow, K., Nguyen, D., Herrick, K. & Akinbami, L (2019) Attempts to Lose Weight Among

Adolescents Aged 16–19 in the United States, 2013-2016, Retrieved from

https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db340-h.pdf

McKenzie, J., Neiger, B., & Thackeray, R. (2016). Planning, implementing, and evaluating health

promotion programs (7th ed.). Pearson.

Rubak, S., Sandbæk, A., Lauritzen, T., & Christensen, B. (2005, April 01). Motivational interviewing: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Retrieved from https://bjgp.org/content/55/513/305

Supportive relationships and environment. (2021). Retrieved from

development

Vliet, J. S., Gustafsson, P. A., & Nelson, N. (2016). Feeling ‘too fat’ rather than being ‘too fat’

increases unhealthy eating habits among adolescents – even in boys. Food & Nutrition

Research,60(1), 29530. doi:10.3402/fnr.v60.29530