Rural vs. Urban

The compositional formats of these images vary among different types of paper gods and were mostly influenced by the composition of the religious paintings used in temples and religious ceremonies. The most common representation is a frontal portrait: the deity is depicted in a frontal pose, often surrounded by a shrine-like setting or frame, very similar to how a sculpture would be placed in a temple. However, even when two paper gods have a similar structure and are of same subject, their styles can be very different due to regional differences.

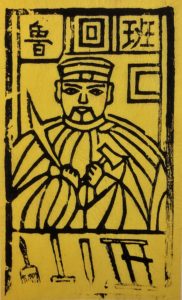

Lu Ban. Woodblock Print, 15×8.2 cm. Before 1966. Neiqiu, Hebei Province. Neiqiu Paper God Editing Committee.

Lu Ban is probably one of the most well-known patron gods in Chinese folk religion, as he was worshiped as the patron god for more than a hundred different professions. In this image from Neiqiu, he is represented as the patron god of carpenters, which is reflected by the tools he is holding and placed in front of him: a knife, an axe, a saw, a chisel, a hammer, and a brush. He is depicted as an artisan wearing a flat hat and has short beard and mustache, with no additional ornaments on or around his body.

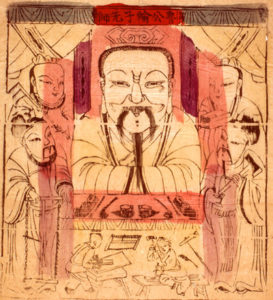

By contrast, the Lu Gongshuzi Xianshi paper god from the city of Beijing, which depicts the same deity and has the same function, adapted a more complex variation of the frontal portrait composition. In this image, the deity is sitting behind an altar table, with curtains above his hand and four attendants on his side, each holding a different carpenter tool. In front of the altar table, two small figures are doing carpentry, which further addresses the function of this paper god. However, the deity himself is depicted as an elder man with a long beard and a mustache, wearing a Taoist robe and crown, which gives him more sense of authority as a god but barely any clue on his relationship with the profession of carpenter.

Like Lu Gongshuzi Xianshi, most paper gods from Beijing follows a similar convention: the deity is depicted as a very authoritative figure, surrounded by a very detailed shrine setting, with curtains and an altar table, and accompanied by two to four attendants, while the paper gods of similar types from the rural areas of Neiqiu often have a minimalistic setting and fewer attendants. This stylistic difference is likely due to the different skill levels of the print makers and the different taste of the costumers between the urban and rural areas. In Beijing, the paper gods were produced and sold by dedicated paper shops, so the print makers were most likely professional artisans who could carve thin and smooth lines and create elaborated images. Whereas in Neiqiu, paper gods were usually made by carpenters as a mean to make extra money, so they might not be as skilled and tend to carve thick and bold lines to make abstract and exaggerated images. At the same time, urban residents, especially residents from the capital city, might have had more access to more orthodox religious beliefs and images, and as the religions spread from urban center into rural areas, they tended to be further transformed and localized, likely due to the lower literacy rate in the rural area.