Americans were preparing to choose a president. One candidate, an exceptionally wealthy man, was a political outsider. If elected, he would be the first to enter the White House having held no prior political office. He was also a partisan outsider. He only recently had joined his party, yet he had beaten well-known establishment figures for the nomination. (His running mate was a dependable partisan and a former congressman.) He faced a Democratic opponent with a long political record. That former senator and cabinet member also had the support of the outgoing commander-in-chief. Prominent Democrats expressed high confidence that their candidate would win. But they were wrong. Voters chose the outsider. That’s right: Zachary Taylor won.

Finding parallels can be fun, a sort of historian’s parlor trick. I’m not the only one to have noted the commonalities between the elections of 1848 and 2016. But this trick has limited analytical value. The Whig Zachary Taylor and the Democrat Lewis Cass, on one hand, and Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton (or Joe Biden), on the other, lived and ran for office in vastly divergent historical contexts. In 1848, the most important issues were the incorporation of new land—the United States had just won everything from Texas to California in the Mexican-American War—and whether White agriculturalists would be allowed to enslave Black laborers there. The candidates themselves did not campaign, except through an occasional open letter or greeting to well-wishers, instead leaving that responsibility to supporters. Neither did the voters choose candidates via primaries; convention delegates freely selected them.

The differences from today, far more than the similarities, can help us to understand the electoral and cultural world of antebellum America. Take, for instance, the first thing I wrote above about Taylor: he was rich. That doesn’t mean he earned money through real estate and entertainment, or through the law and writing books, like recent well-off chief executives. Taylor owned over 130 human beings. His correspondence during the campaign shows his continued attention to the plantations where those enslaved men, women, and children earned him profits. Slavery became so central an issue that, though both major parties generally defended it, some former Democrats and Whigs split off to form a third party around that issue. Free Soilers, who nominated Martin Van Buren, shared opposition to slavery’s expansion into the new territories (though not usually to its existence). Taylor remained publicly vague on that question. Vice-presidential nominee Millard Fillmore, meanwhile, was accused by opponents of being an abolitionist. His supporters defended him from that false and, in the racist politics of the day, libelous charge.

Taylor’s outsider status also reveals how different his time was from ours. Besides an absentee planter, he was a career soldier who had risen to become one of the army’s top generals. Today we see such a career as a path to the White House, one pursued by Dwight D. Eisenhower, Ulysses S. Grant (though he had also acted as secretary of war), and Taylor himself. But not in 1848. True, several former army officers had become president, from George Washington to Andrew Jackson to William Henry Harrison. But each of them also had held civil government posts. General Taylor, who had not, thus appeared unqualified to some despite his military attainments. His own commander-in-chief, James K. Polk, declared him a “poor old man . . . [who] is totally ignorant of public affairs.”

Not only had Taylor never held civil office. Until his own election, he had never voted. That history, without context, seems to feed into detractors’ image of him as ignorant and undeserving. But, in fact, he rarely had the opportunity to vote. Taylor spent election days wherever the War Department posted him, often at frontier forts and almost always away from his Kentucky and Louisiana homes. Absentee or mail-in ballots garner much attention today, but few states offered them before the Civil War. Most members of the military stationed away from their places of residence, however patriotic and however politically opinionated, could not vote.

Curiously, even in 1848, when Taylor commanded his army division from his hometown of Baton Rouge, he may not have cast a ballot. The New Orleans Delta reported, possibly in jest or possibly not, that he spoke after the election with a stranger who did not recognize him. In anonymity he declared, “I did not vote for General Taylor; and my family, especially the old lady [wife Margaret Mackall Smith Taylor], are strongly opposed to his election.”

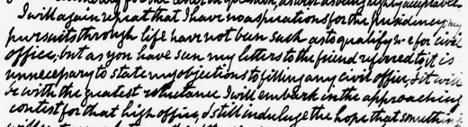

Taylor to Unknown, December 16, 1847, denying interest in and qualifications for the presidency. Zachary Taylor Papers, Library of Congress.

Taylor’s indifference or opposition to his own election runs throughout his letters. Even in private correspondence, which had little chance of becoming public and thus little value in deceiving voters, we keep finding his expressions of reluctance. In 1847 he told brother Joseph P. Taylor, “I deeply regret” that “my friends had connected my name with the presidency,” and told son-in-law Jefferson Davis that he hoped the party conventions, when selecting candidates, “will pass me by if not unknown, at least unnoticed.” He went so far as to tell another correspondent—in effect agreeing with his opponents—not only that “I have no aspirations for the presidency” but also that “my pursuits through life have not been such as to qualify me for civil office.” He was willing to serve if chosen, but claimed neither interest in nor joy about the prospect. How honest his humility and selflessness were is up to the reader. We look forward to publishing our transcriptions of these letters online next year, so you can read them in entirety and decide for yourself.

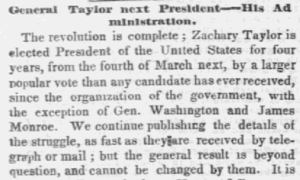

In some ways, elections in Taylor and Fillmore’s day were becoming more like ours. By 1832, nearly every state held a popular vote for president. (Only South Carolina’s legislature still appointed electors without the people’s input.) The election of 1848 was the first when, under a law of 1845, every state voted on the same day—as today, the Tuesday after the first Monday in November. In previous years, states had voted on different days spread as much as weeks apart. Partly as a result of this change, Americans learned relatively quickly—within four days, unofficially—whom they had elected.

New York Weekly Herald, November 11, 1848

One other change created an awkward situation hardly imaginable today. In 1847 the United States introduced its first federal postage stamp. Until then, Americans had paid to receive mail rather than to send it. Now correspondents could choose whether to send letters postage paid or postage due. Taylor preferred the former. He informed his local postmaster, in fact, that he would not accept any postage-due mail. As a result, when the Whig National Convention nominated him for president in June 1848 and sent him a letter, stamp-free, notifying him of that result, he never got it. Weeks later, not having heard back from him, they sent another letter—postage paid.

The letters I cite above reflect the diligent work of students who have been busy transcribing the original manuscripts. Last month Alyssa Moore and Alexander Pando Kiprof, both seniors at St. Olaf College, joined our project as interns for the fall semester. Both already have added new letters to the corpus that we’ll begin publishing next year.

Meanwhile, in August, Gabriella A. Siegfried completed her summer as the project’s editorial assistant. I thank her for the enthusiasm and hard work she brought to the job. Gab both transcribed letters and, using her degree in Spanish, translated those that Taylor and Fillmore received from Latin American heads of state. She made major contributions to our progress, and I wish her well as she continues to pursue her MPA here in American University’s School of Public Affairs.