Earlier in this blog, I discussed our processes for locating Zachary Taylor’s and Millard Fillmore’s letters and for transcribing and proofreading them. Those tasks continue, as we are always finding more documents in libraries, archives, and private collections. Our database now includes over 4,500 letters by or to the twelfth and thirteenth presidents, plus hundreds of enclosures and cover letters.

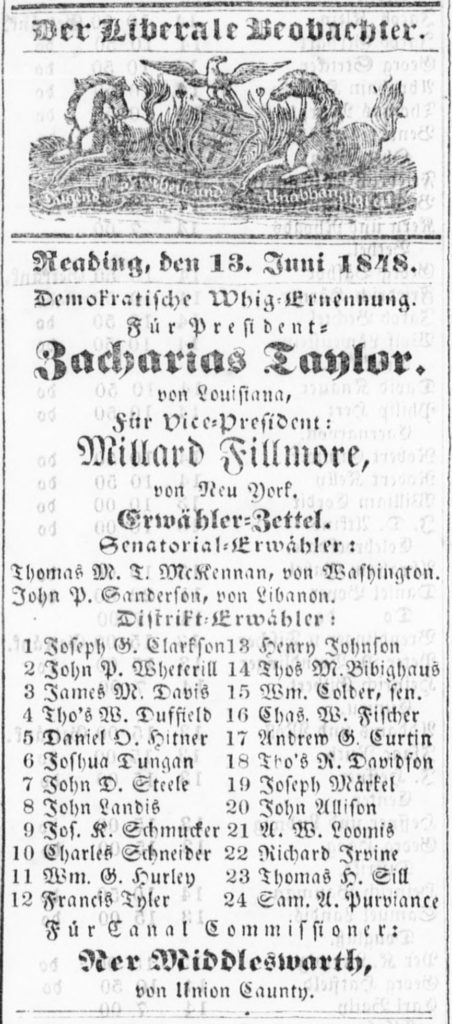

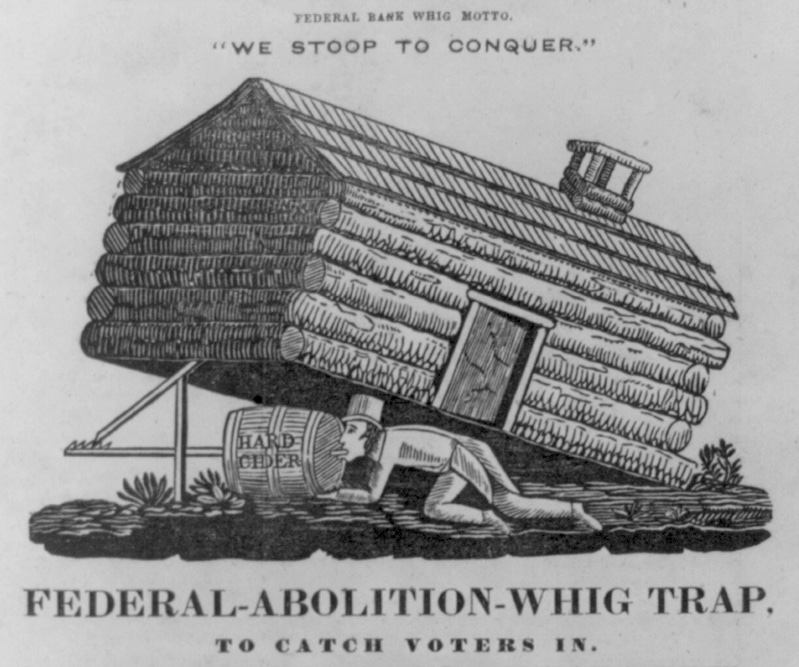

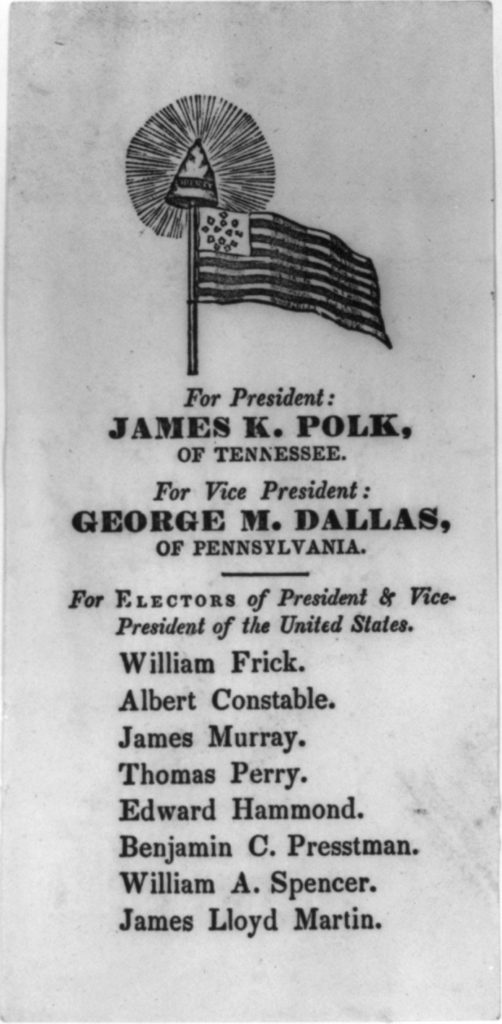

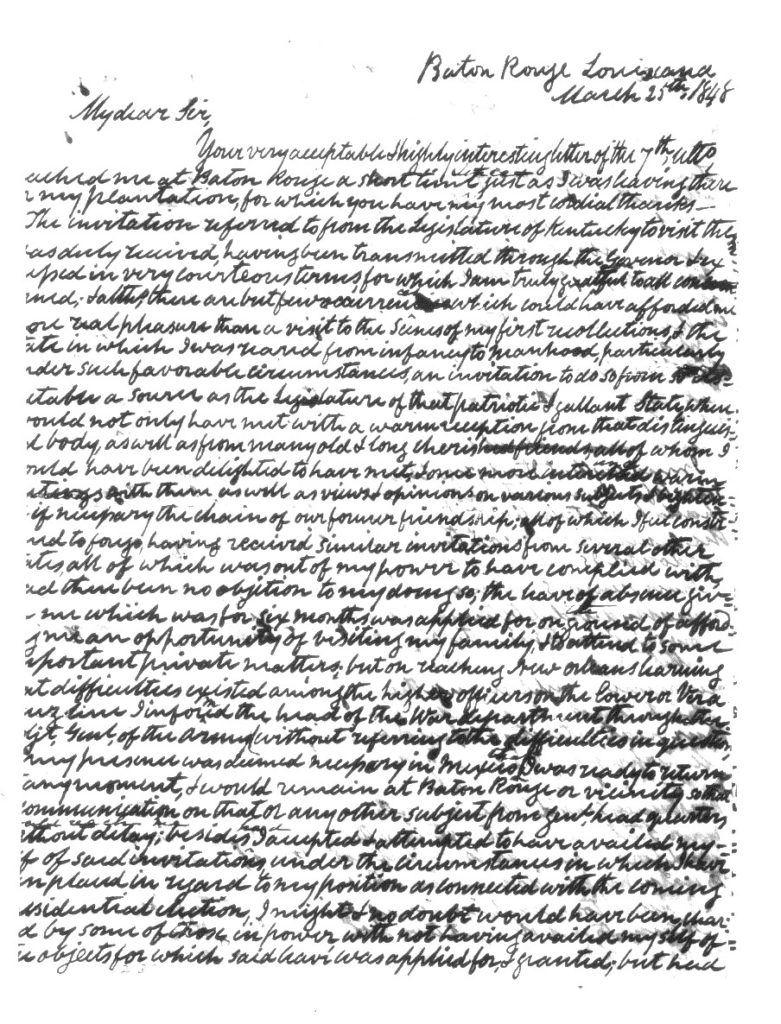

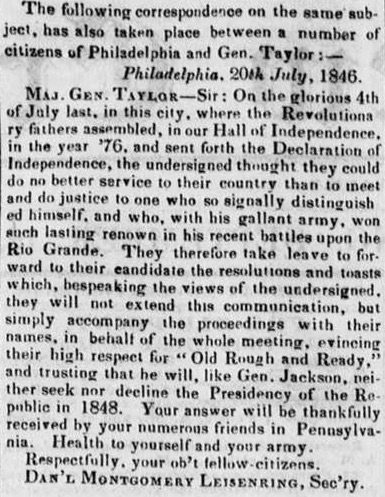

Mostly, though, we’ve moved on to the next stages of documentary editing. As you may recall, we intend to publish three print and digital volumes of Taylor’s and Fillmore’s letters from 1844 to 1853, the decade preceding and including their presidencies. Volume 1, which we will send off to the publisher next winter, will cover from January 1844 to June 1848, ending just after the Mexican-American War and the two men’s nomination for president and vice president. By last summer we had located nearly all surviving letters from that period (but please tell us if one’s in your attic!) and transcribed and proofread those that will appear in the volume.

Today I want to tell you what we’ve been up to lately. It’s time to discuss what documentary editors do after finalizing the transcriptions.

I’ve subtitled this entry “Translating the Past.” For some letters, the next stage is literal translation. Because most people studying US history read English, that will be the language of the edition. Both Taylor and Fillmore were native speakers, and we have yet to find any letter than either man wrote in another language. But they received letters from diverse people around the United States and beyond. Many immigrants and their US-born children continued to use continental European tongues, many Native Americans used those of their own nations, and diplomats often wrote in French, the literal lingua franca of their profession. During the Mexican-American War, Taylor corresponded with Mexican leaders and citizens who wrote in Spanish. So the incoming letters, unlike the outgoing ones, are a linguistically diverse corpus.

Our first volume will include two dozen letters originally written in Spanish and one originally written in French. For some of those, we have contemporary translations. Taylor’s aide-de-camp (and later son-in-law) William W. S. Bliss, for example, was a talented linguist who translated for the general. In those cases, we will publish the English version that the future president read. But if we only have the Spanish or French, we will translate it for our readers. Editorial colleagues and American University students are helping us with that process. Thus we can include letters by such people as Mariquita Lopez, of Matamoros, Mexico, who sought Taylor’s help to support her indigent family (the letter’s held here), and Ynocenio Leyba, likely a Mexican soldier, who had lost his right foot and was lying in a hospital destitute of money and clothing (here).

Having found the letters, transcribed and proofread them, and, if necessary, translated them into English, we’re ready to publish, right? No. Of course not. My blog entries are rarely this short. Besides, I’ve titled this one “Annotation.”

Our goal is to make original documents from US history widely accessible. Accessible means more than available. Please pardon what may sound like semantic hairsplitting. We editors often use available to mean “in a place where readers can find them” and accessible to mean “in a condition in which readers can use them.” Under these definitions, we could make the letters available by publishing images of handwritten manuscripts. Or, to be kinder to users’ eyes and screen readers, we could do so by publishing transcriptions and translations. But would those be accessible—would they be usable?

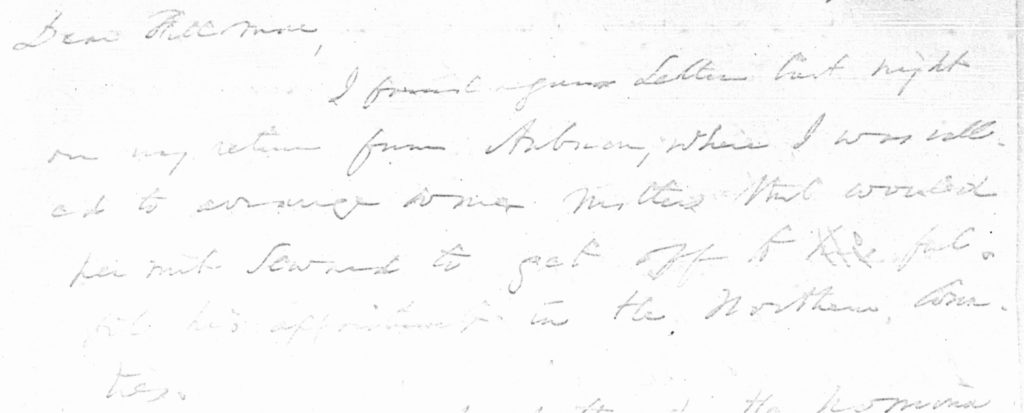

Consider an example I cited in my blog entry on transcription. Here’s the beginning of a letter that Thurlow Weed wrote to Fillmore on September 19, 1844:

Thurlow Weed to Fillmore, Sept. 19, 1844 (Millard Fillmore Papers, SUNY-Oswego)

Weed’s handwriting was terrible (or, as editors say, “a fun challenge”), so publishing just the image would be cruel. But say we were to publish a transcription:

Dear Fillmore,

I found your Letter last night on my return from Auburn, where I was called to arrange some matters that would permit Seward to get off to his fulfil his appointments in the Northern Counties.

Now you can read the text. But what does it mean? Someone reading The Correspondence of Zachary Taylor and Millard Fillmore, and with access to its introduction, probably knows who “Fillmore” was. But who was “Seward”? Who, for that matter, was Weed? Which letter of Fillmore’s is he referencing? To understand Weed’s letter and to use it to study history, you need to know these things. Sure, Wikipedia will reveal that William H. Seward was New York’s former governor and that Weed was an Albany journalist and Whig Party manager. But do you trust Wikipedia without checking it against reliable primary sources and historical research? I don’t recommend that. Fact checking is important and takes time. And we’ve only gotten through the first of thirteen paragraphs in the letter.

Besides, most people and events aren’t famous. They aren’t on Wikipedia or other freely available (let alone trustworthy) websites. Let’s move on from Weed. Consider a letter that Amy Larrabee Cotz and I have been working on recently (held here). Anthony Bracklin wrote this to Taylor on June 4, 1846:

I was sent to the, Genl Depot at Fort Columbus and from their^re^ assigned to Company ‘H’ 1st Arty which Company I joined at Eastport, where, as the Company ^was^ over the number of laundresses alowed by law, my wife lost her rations on account being the youngest.- Impossible to support a family with $600^””^ dollars a month, and a single ration per day, separated hundreds of miles from my family; I tried to find a chance for transfer to a Company where a laundress is wanted

To understand this letter, we need some background. Bracklin tells us that he’s a soldier in a particular army unit and that he served at Fort Columbus and then Eastport. But additional information on him would be nice. Where was he from? What years did he live? Did he have much military experience? Where were Fort Columbus and Eastport? Most important to the letter, who was Anthony’s wife? He doesn’t name her. What’s this business about “laundresses alowed by law”?

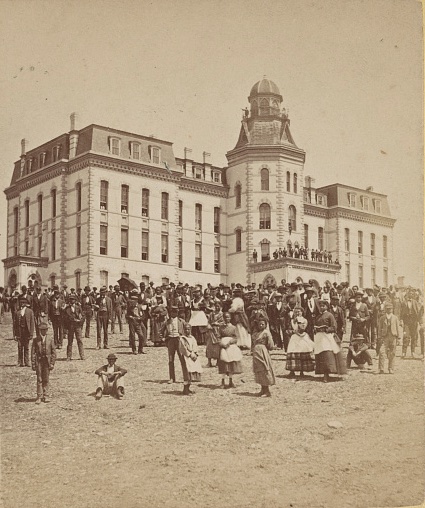

Wikipedia or a Google search will not answer most of these questions. We spent significant time going through other historians’ research and through primary sources beyond Anthony’s letter. We then wrote footnotes, which we will include with the letter when we publish it, telling readers that he was a longtime soldier from New York (where Fort Columbus and Eastport were); that his wife was Mary A. Bracklin, who later lived independently while working as a washerwoman; and that the army hired women as laundresses from 1802 to 1883. Military enlistment records, city directories, and historical newspapers, most of them neither freely available to nor easily navigable by our readers, were especially helpful in researching this letter’s annotation.

In short, we editors provide readers with the knowledge that a letter’s author assumed the recipient had, plus additional information that helps put the letter in its historical context. Or, as Bianca Swift wrote in her excellent introspective essay about digitizing the works of Charles W. Chesnutt, “We try to make his world a formula we can understand.” This is how I think of annotation: even if a letter is in English, we editors are responsible for translating references such as “Seward,” “my wife,” and “laundresses alowed by law”—perfectly clear, perhaps, to the letters’ original recipients—into explanations meaningful to people today. We identify people, institutions, events, and other topics in the letters so that twenty-first-century readers can use them to learn nineteenth-century history without all the preliminary work needed to understand the letters themselves. That doesn’t mean we find everything. Swift, when reading Chesnutt’s reflections on the challenges of a Black lawyer and writer, finds herself “wonder[ing] if he cried” and unable to answer the question for her readers or herself. We share the basic (but often hard-to-find) background so that readers can mine the letters for what they reveal about the nineteenth-century world.

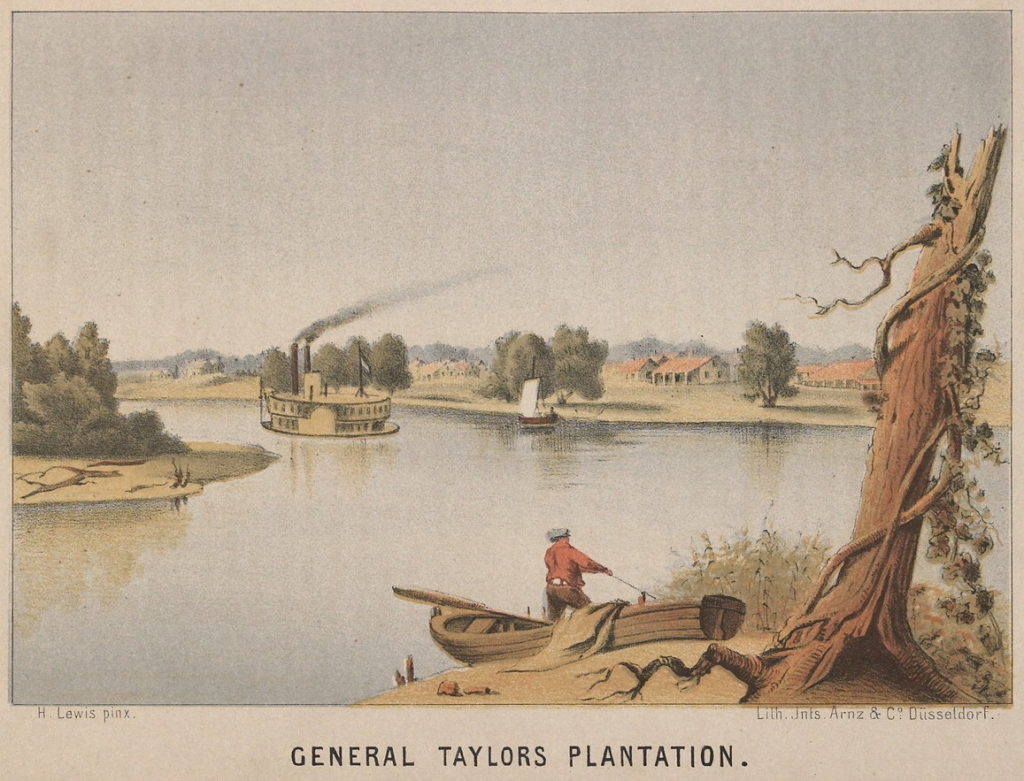

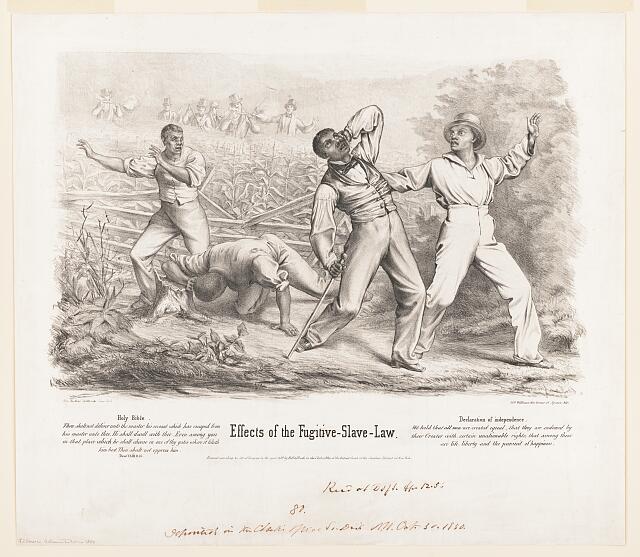

Sometimes the references we must identify (or translate, in this figurative sense) verge on the comical or the maddening. Zachary Taylor, when discussing various relatives in letters to his daughter, often refers to two of them as “Mr. & Mrs. Taylor.” The family, of course, included quite a few couples by that name. From the context and comparisons among the letters, we were able to determine which couple he meant. The dreaded “Mr. Smith” reference presents a similar challenge. And, as a leader of a society that threatened to divide Black families and in which Black family names were uncommon, Zachary Taylor referred to people he enslaved only by first names—as “Mary,” for example, even though he enslaved multiple women named Mary. We do our best, using records behind online paywalls, in physical archives and libraries, and on our own bursting bookshelves, to translate the “Taylors,” “Smiths,” and “Marys” into real individuals with real stories that give the letters meaning.

Before I go, I want to share a conversation I recently had about (surprise, surprise) Millard Fillmore. The American History Hit podcast kindly invited me to speak with Don Wildman about him as part of a series on all the presidents. (Dr. Cecily Zander did the one on Taylor.) We covered quite the gamut of Fillmore topics, from slavery’s expansion to controversy over Freemasonry to trade with Japan and China. You can listen to our conversation and find the rest of the series here or, as they say, wherever you get your podcasts. Thank you, Don and the History Hit team, for this fun opportunity.