The new year, at our project, began with some excitement. On January 10 we released our first-ever teaching guide. It features four previously unpublished letters written by or to Millard Fillmore between 1844 and 1848. They discuss the US annexation of Texas and the closely related debate over slavery. Short introductions and questions for discussion and writing accompany the letters. Educators can use the guide to teach students in eleventh- or twelfth-grade US history courses about these key issues in antebellum history and about the use of primary sources to understand the past. Furthermore, with volume 1 of The Correspondence of Zachary Taylor and Millard Fillmore still a few years away (but progress moving apace!), the guide is our very first publication of letters. Anyone interested in America before the Civil War can begin using these newly accessible documents.

Sharing these primary sources got me thinking about how we find them in the first place. I mentioned in a previous blog entry that most of our work early in 2021 comprised two tasks: locating Taylor’s and Fillmore’s letters and transcribing them. I spent most of the entry describing the transcription process and its perils. I only briefly outlined the location process—or the canvass, as we call it—which at the time consisted almost entirely of remote service requests to repositories that had curtailed visits by researchers to slow the spread of COVID-19. Given their immense help, both in identifying collections that include Taylor or Fillmore correspondence and in scanning that correspondence for our project, I cannot adequately praise the dedicated archivists and librarians.

In the fall, between the pandemic’s Delta and Omicron surges, the world of research started to return to normal. We finally were able to visit some repositories in person. Associate Editor Amy Larrabee Cotz went to the New York Public Library and the US Army Heritage and Education Center, and I went to Duke University’s David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Contracting for us, Ed Bradley hunted for letters at the Library of Congress, and David Gerleman did so at the National Archives. This seems like a good time, then, to explain what we editors really do when we “go to the archives.”

Well before we leave home, we plan out where we’ll go and what we’ll do there. Online databases, such as ArchiveGrid, the Social Networks and Archival Context Cooperative, WorldCat, and the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, help us identify repositories and specific document collections containing relevant materials. Our own research in bibliographies, historians’ writings, and known primary sources supplement those. Once we contact the repositories’ staff—again, so much comes down to those amazing archivists and librarians—they help us narrow down which boxes and folders full of documents, or even which individual letters, we need to see. By the time we get in a car or an airplane, we have a pretty specific plan of action.

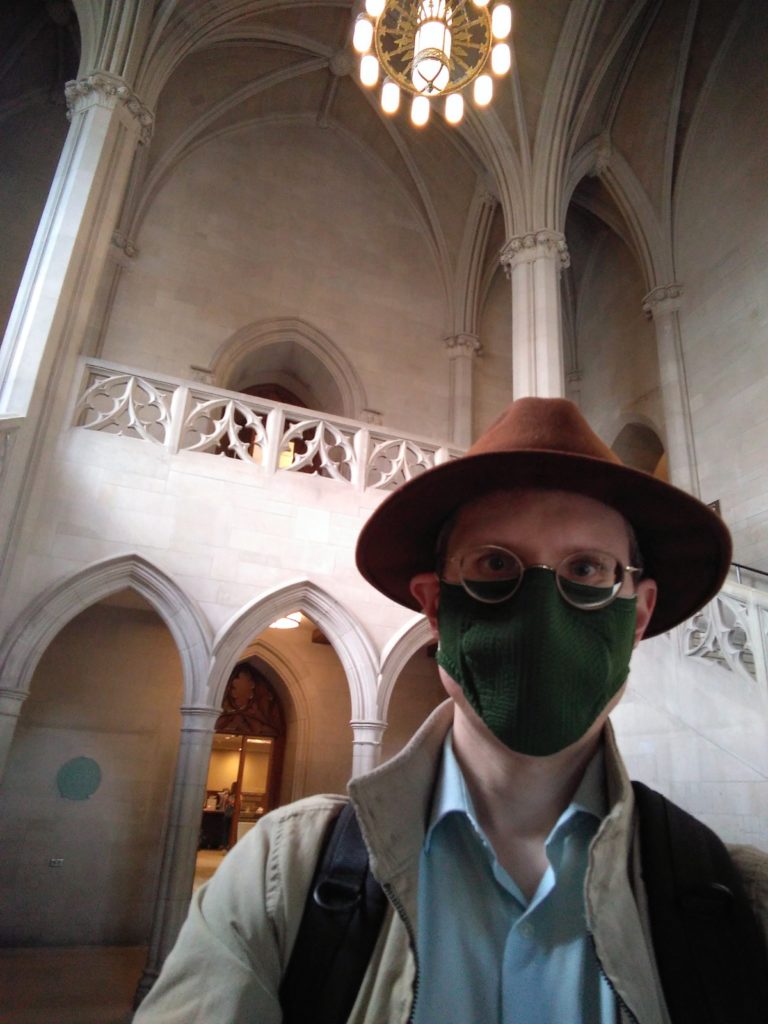

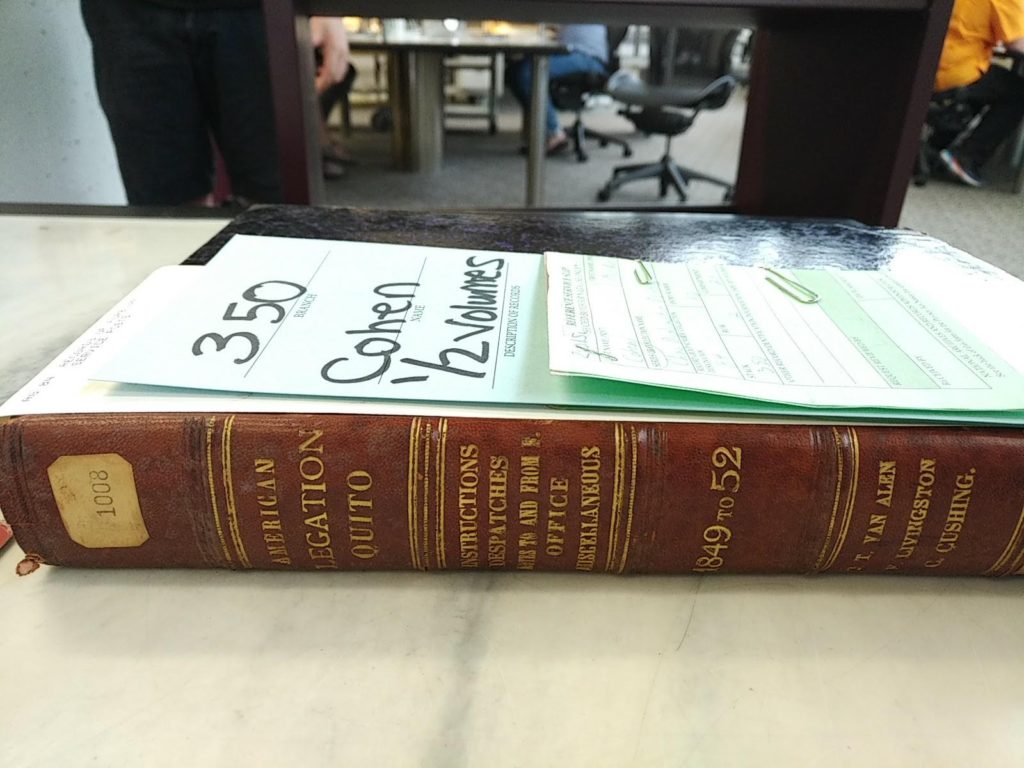

On arriving at the facility—after, maybe, taking a research selfie—it’s simply a matter of going through the documents. Staff, in many cases, have kindly set aside the containers we need so that they’re ready to bring into the reading room. We go through the boxes, folders, and bound volumes, page by page, following the repository’s procedural guidelines to protect the documents while determining what is and what isn’t a Taylor or Fillmore letter. When we find such a letter, we photograph or scan it for the project’s records, making sure also to record the collection and container it’s in so that we can properly cite it and, if necessary, locate it again. After hours or days of this, we’re back on a plane with a camera full of manuscript images.

Your editor at Duke’s Rubenstein Library

A volume of bound manuscript letters at the National Archives, College Park, MD

Back home, we accession the newly found documents into our project’s database. In the old days—three years ago, for me, when I was finishing up a documentary editing project launched in the 1950s—that “database” was made of paper. Each document was printed out (or just photocopied in the first place) and placed in a folder; each was described on a 3″ x 5″ card inserted into a card catalog. For the Taylor-Fillmore project, launched in the digital age, the database is electronic. Different projects use different software to manage their collections. We use DocTracker, a FileMaker Pro solution developed at the University of Virginia (with support from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission, a generous sponsor of our own project) specifically to accommodate the needs of documentary editors. Once we enter the basic data for a letter—including who wrote it, who received it, the date, and the repository location—we easily can review and search all the letters to select which to publish and to track our progress in transcription and other tasks. The images of the manuscripts, meanwhile, are stored electronically and identified with the corresponding records in DocTracker.

Even when travel is safe, not all parts of the canvass require in-person visits to repositories. Many documents have been preserved on National Archives microfilm reels, which we can review at home, or on the Millard Fillmore Papers, a microfilm series of which the University of Virginia’s Miller Center has generously shared digital scans. Many repositories, meanwhile, have digitized their own collections and posted the images online. Several of the Taylor letters from Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library are featured in Yale’s Digital Collections, for example, and the Library of Congress has digitized many of its presidential collections, including the Taylor Papers and the Fillmore Papers. Fold3, a massive digital collection of military records, includes Taylor documents from the National Archives. Several other databases, including the Library of Congress’s open-access Chronicling America website, feature searchable historical newspapers in which many of the presidents’ letters were published. Pouring through these, we find ever more letters.

The result? We’ve located, imaged, and accessioned thousands of letters written by or to Taylor and Fillmore between 1844 and 1853. We’re adding more all the time. And we could not do this so efficiently and thoroughly without the prior work and current aid of archivists and librarians who gather and organize historical documents, digital humanists who create online databases of documents and repositories, and editors and public servants who build tools such as DocTracker. Following up on their contributions and our canvass, we’re able to transcribe, proofread, annotate, index, and publish primary sources for the use of all students of history.

Speaking of students (pardon the forced segue), this month we welcomed two new graduate students to our staff. Nicholas Breslin is earning his MA in public policy here at American University’s School of Public Affairs. Ian Iverson is earning his PhD in history at the University of Virginia. As editorial assistants, they are helping us to transcribe and, yes, to locate Taylor’s and Fillmore’s letters. It had been a pleasure beginning to work with them over the past few weeks.