Those of us who celebrate are counting down the days until Christmas. So I’d love to write a blog post about the holiday festivities enjoyed by Taylor and Fillmore. I’d love to share the greetings they exchanged with family and friends. But, for the most part, I can’t. That’s because Christmas was very different in the 1840s from the holiday we know today. In many ways, it was less important.

Let’s look at the letters. So far, Amy Larrabee Cotz, our student contributors, and I have read several thousand letters that the two men wrote or received. Of those, at least five mention Christmas. You read that right: five. And those mentions aren’t all jolly. For Taylor, Christmas was a convenient marker in the calendar of slavery-based agriculture. On December 29, 1845, he told overseer Thomas W. Ringgold that he hoped the men and women who worked his Mississippi plantation had picked six hundred bales of cotton by the twenty-fifth (Beinecke Library, Yale University). Planning ahead on April 2 of the following year, he noted that “the crop usually should be finished by Christmas” and directed Ringgold to assign “the good axmen” to chop wood after the holiday.

Fillmore’s references to Christmas are more cheerful. On November 28, 1847, he told his daughter, Mary Abigail (called Abby), that he and wife Abigail Powers Fillmore “hope to have the pleasure of spending Christmas with you and [son Millard] Powers.” A week later, apparently seeking assurance that the feeling was mutual, he added that they hoped to see her “in Albany at Christmas. . . . Will you not be glad to see us? I think you will.” With Abby and Powers away at school, the family looked forward to a holiday reunion. (Both letters are at SUNY–Oswego.)

That’s pretty much it. Another letter, written to Fillmore, merely notes that a man and a woman married on Christmas Day. Even letters written on that day don’t mention it as such. Given how little is there, it’s no wonder that even the rather well sourced “White House Christmas Cards” website admits “there is no information as to how the President [Taylor] and his family celebrated the holidays” and has little more to say about Fillmore.

Other historians have found a little more about how they spent the day. Mike Henry, in the children’s book Christmas with the Presidents, notes that relatives of the Taylors visited the White House for coconut cake on Christmas Day 1849 and that Fillmore joined a “bucket brigade” to fight a fire at the Library of Congress on Christmas Eve 1851. Robert J. Scarry, author of Fillmore’s most thorough biography, tracked down letters from earlier years—before our project begins in 1844—about the gifts Millard and Abigail gave to their young children. In 1837, while away in Washington owing to Millard’s service in Congress, they sent back to New York a wax doll for Abby and a book for Powers. Five years later Millard gave everyone books that he had purchased at an auction on Christmas Eve: Album Des Salons for Abigail, Gift of Fairyland for Abby, and Shakespeare’s plays for Powers. At least once the husband and father’s late shopping trips turned what he meant as Christmas presents into “New Year’s presents.”

Why not more? Given that the large majority of White and Black Americans in that era were Christian, Americans of today who see Christmas as the most recognized day of the year may wonder why it’s not more prominent in the correspondence. The answer is that Americans did not celebrate the holiday consistently or in the modern way until after the Civil War. Christians since the fourth century had commemorated Jesus’ birth on December 25, and most of the English and French colonies that would become the United States marked it with religious services, feasts, games, or dances. But, notes Penne L. Restad in Christmas in America: A History, my go-to history of, well, Christmas in America, Americans after the Revolution celebrated fewer holidays than they had before it. Fanny Kemble, an actress accustomed to festive Christmases in her native England, lamented while among Americans in 1832 that “Christmas day is no religious day and hardly a holiday with them” (17).

Library of Congress

Some areas did observe it, though, and it became more prominent nationally over the next decade. By Christmas 1841, when St. Paul’s Cathedral in New York was “‘jammed’” (32) with Catholics, some previously reluctant Calvinist clergymen had begun referencing the day in their sermons. Green flora and candles became cross-denominational symbols of the day; alcohol increasingly “fueled” its “amusements” (37). St. Nicholas, almost never mentioned in colonial times, gradually became associated with Christmas in the United States after Washington Irving included him in Knickerbocker’s History of New York (1809) and an anonymous poet, either Clement C. Moore or Henry Livingston Jr., introduced his more-or-less modern image in “Account of a Visit from St. Nicholas” (1823). German immigrants, meanwhile, brought the notion of Christmas trees to America.

Whites in the agricultural South enjoyed feasts and games on the post-harvest holiday. Many enslaved Blacks got a few days off from work and gifts of clothing or feasts from the masters who dictated their lives. We have yet to find evidence of whether Taylor allowed the Black families on his plantations such holiday benefits, though his general wish to maintain their health and thus their ability to labor for him makes it likely. Some enslaved people, as Robert E. May explains in Yuletide in Dixie: Slavery, Christmas, and Southern Memory and this article, endured harsh physical abuse on Christmas—as on other days—or were forced to wrestle or drink alcohol for White people’s “amusement.”

Library of Congress

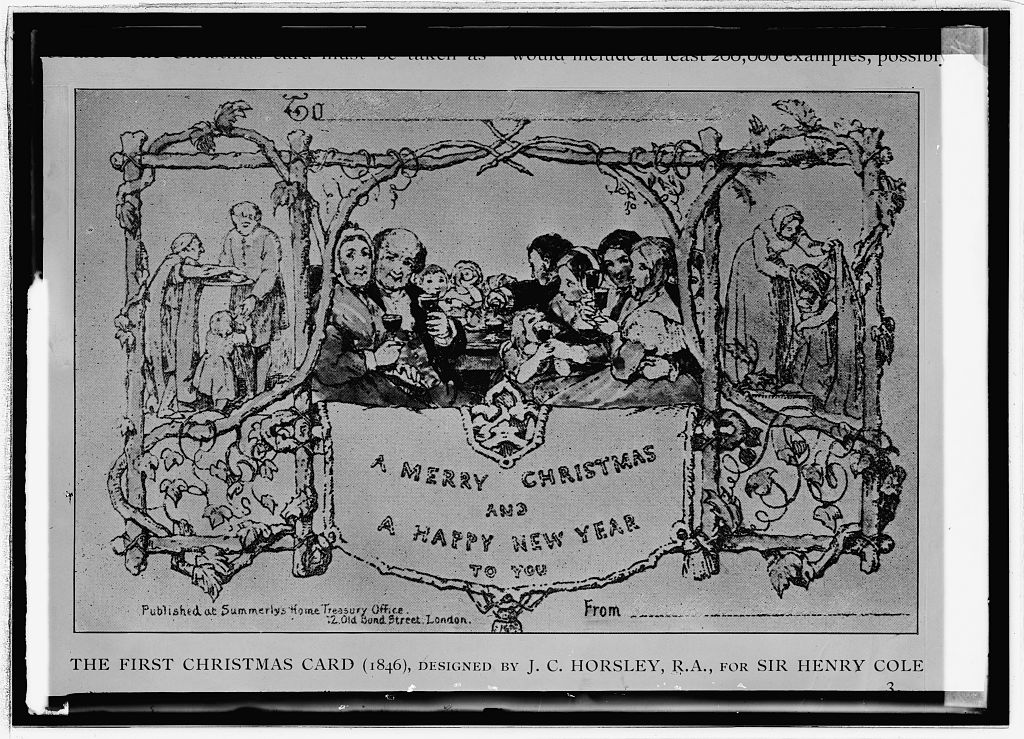

In short, Christmas in the 1840s was still in development. Celebration among US Christians was far from universal, let alone uniform. Traditions and images that we consider iconic were just coming into fashion. Christmas cards existed then but didn’t become common until after the Civil War. The Fillmore family’s separation while Millard served in government posts and the children boarded at school, and the Taylor family’s separation while Zachary served in Mexico, created particular obstacles against sharing what would become known as holiday traditions. So, while the Fillmores at least seem to have recognized and valued Christmas, it makes sense that it played a minor role in both families’ lives and in both men’s letters.

Today many families, friends, worshipers, and coworkers do gather (when safe amid pandemic concerns) to honor Christmas, other winter holidays, and each other. I wish all who do so a happy and healthy celebration and end of the year.

Earlier this month, we at the Taylor-Fillmore project held our own gathering. This wasn’t about a holiday, but rather about introducing ourselves. I have had the pleasure this semester of working with six staff and student colleagues to locate, transcribe, and proofread the presidents’ letters. But, as they work in different locations and on different tasks, they had not all met each other. So, finally, we came together virtually for all to share their interests and what they’ve found in the correspondence. Several have completed their time on the project, and all have made essential contributions to making primary sources widely accessible. I genuinely thank associate editor Amy Larrabee Cotz, editorial assistant Alaysia Bookal, volunteer associate editor Cameron Coyle, and interns Brendan Lawlor, Abigail Peterson, and Leila Rocha Fisher.