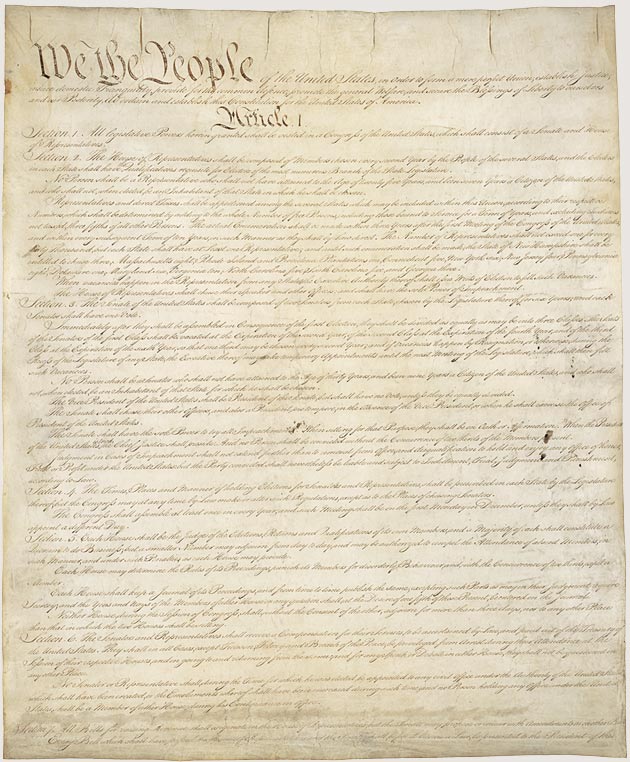

United States Constitution

This Saturday is Constitution Day. It commemorates September 17, 1787, when thirty-nine politicians in Philadelphia signed the US Constitution. More broadly, the day recognizes the document itself and the federal government—and, once it was later amended, individual rights—that it established when it took effect in 1789. Since 2004, when Congress legally created the holiday, communities and institutions across the country have held educational or celebratory events. The National Constitution Center’s are among the most prominent. Here at American University, the School of Public Affairs will today (5:30 to 7:00 ET) host a conversation between Yale’s Steven Smith and our own Sarah Hauser on “Is Patriotism Worth Preserving?” You can register to watch it live here.

Two future presidents signed the Constitution: George Washington and James Madison. Zachary Taylor and Millard Fillmore played no role, for the simple reason that Taylor was two years old at the time and Fillmore was not yet born. (Taylor’s father and Fillmore’s grandfather did fight with the colonists in the Revolutionary War.) Once they entered political life, however, they engaged with and wrote about the document quite a bit, long before taking their oaths as president and vice president to protect and defend it. We have found many of their thoughts on the Constitution in their pre-presidential letters, especially Taylor’s during the Mexican-American War and the early presidential campaign. This seems a good week to share some.

Fillmore discussed the Constitution chiefly in the context of Texas annexation. In 1844, when many White Southerners supported incorporating that republic into the United States, many Northerners who opposed slavery’s expansion or slaveholders’ political power wanted to keep it out. A group of Ohioans led by Samuel P. Chase—who later served in Abraham Lincoln’s cabinet and on the US Supreme Court—wrote to Fillmore on March 30 with their views. Annexing Texas with slavery legal, they averred, would come “at the expence of . . . a violated Constitution.” On June 25, 1845, a “Convention of the People of Massachusetts opposed to the Annexation of Texas” added their voices that “the Constitution has been violated . . . for an unconstitutional object.” They argued that the process used for annexation, a joint resolution of Congress, ignored the document’s requirement that it be done by treaty. For his part, Fillmore told another Ohio committee on June 14, 1844, that he opposed the expansion of US slavery into Texas, the increased power of slaveholders, and the potential for “civil war.” But he mentioned the Constitution only in general terms, recalling “that our ancestors have bequeathed to us a free Constitution, heretofore blessing and binding together a united and happy people,” without opining on what it dictated regarding Texas. (All Fillmore letters not otherwise cited are at the State University of New York–Oswego.)

As a candidate for vice president, Fillmore continued to invoke the founding document in a celebratory but vague and, by the standards of the day, moderate way. He told Erastus D. Culver on June 15, 1848, merely that a president should “stand by the constitution & all its guarantees.” On May 9 he wrote to Hiram Kitchum with a little more substance: “with Slavery in the States we have nothing to do, but to abide by the compromises of the Constitution.” Although he didn’t specify what those compromises were, he knew that they included sending those who escaped from plantations back to their enslavers and counting three-fifths of enslaved Black Americans when calculating congressional representation for the White Americans living nearby.

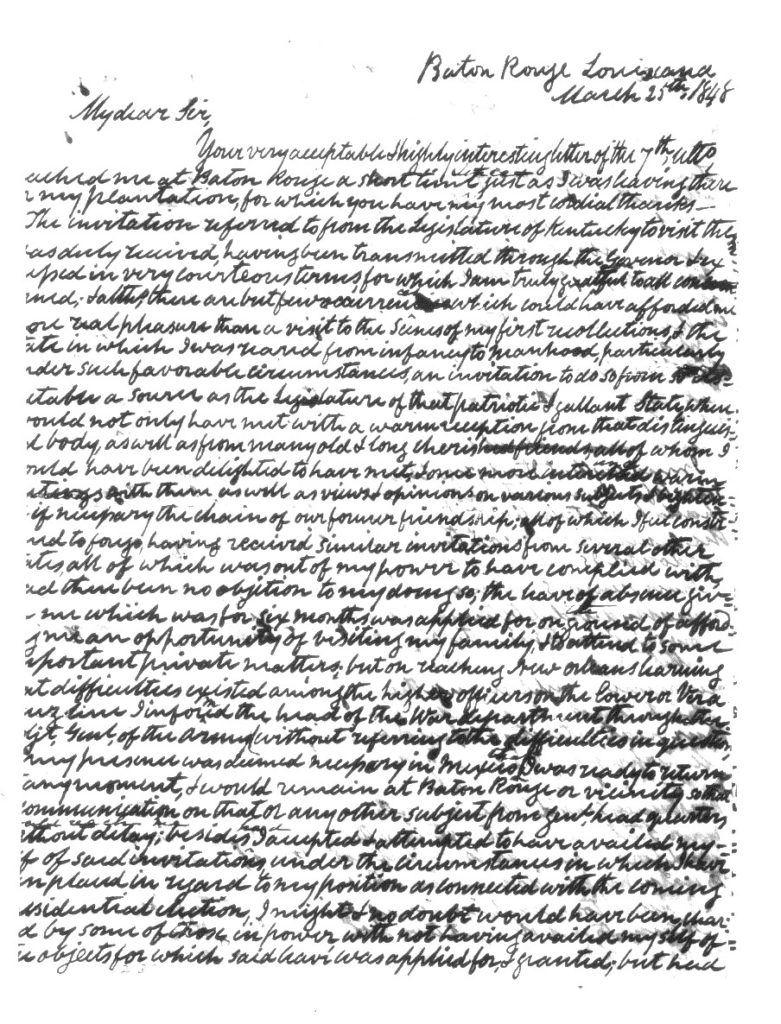

Taylor, the presidential candidate who kept saying he wasn’t interested in or qualified for the presidency, was even vaguer than Fillmore on his constitutional views. Occasionally he opined on the document’s application to military matters. On September 3, 1846, early in the Mexican-American War, he wrote to his son-in-law Robert C. Wood. He insisted that “Volunteers,” as opposed to professional soldiers, “were never intended to invad or carry on war out of the limits of their own country, but should be used, as the constitution intended they should be for enforcing the execution of the laws, & repelling invasion” (Huntington Library, Taylor Papers). He also sometimes used it to criticize the Democratic Party and the James K. Polk administration. On March 25, 1848, he told Whig senator John J. Crittenden that “if the present party are to rule the destinies of the Country for a few years longer, there will be nothing left of the Constitution but its name.” He didn’t specify which constitutional provisions he thought the Democrats had violated (Library of Congress, Crittenden Papers).

Taylor to John J. Crittenden, March 25, 1848 (Library of Congress)

More often, Taylor merely promised that, if elected, he would follow the Constitution’s guidance and its limits on presidential power. In a letter to F. S. Bronson, for example, dated August 10, 1847, and published in numerous newspapers and pamphlets, he refused to make any “pledge” regarding his actions in the presidential office beyond “discharging its functions to the best of my ability, and strictly in accordance with the requirements of the Constitution.” He often made similar assertions, arguing that voters should support him (or not) based on his character rather than his political views. In another oft-published letter, dated March 29, 1848, he went so far as to assert “that my opinions, even if I were the President of the United States, are neither important nor necessary” (Washington Daily Union, October 14, 1848). Elsewhere he privately explained his reasoning. He told Kentucky planter William C. Bullitt, on October 10, 1847, that “the President [should] confine himself to the duties confided to him by the Constitution.” These, he continued, were limited to suggesting “measures” to Congress, “leaving it to that branch of the government to act on, or dispose of the same . . . ; to veto such laws as he deems unconstitutional or otherwise, passed by that body, & to sign such as he approved, & see they were faithfully executed. . . . [T]he President should be in some measure like the judge on the bench, that he ought not to give his opinion on important matters until the proper time arrives for his doing so” (Filson Historical Society, Bullitt Family Papers, Oxmoor Collection).

Reactions varied to Taylor’s pro-Constitution but light-on-specifics campaign rhetoric. A Philadelphia committee led by George W. McClellan praised his making “no pledges but those contained in the official oath at your inauguration, and with the declaration of independence and the constitution as your guides” (Washington Semi-Weekly Union, April 30, 1847). New Yorker James B. Eldridge, however, complained to Fillmore about Taylor’s refusal to disclose his opinions. What measures, Eldridge wanted to know, would Taylor promote or oppose? “I know,” he acknowledged, “General Taylor has said he shall be guided by the constitution if elected President. But that must be understood that he will respect the Constitution as he understands it.” And how was that?

Each president and each presidential candidate, whether upfront about it or not, must interpret the US Constitution and its application to the key questions of the day. But they are not the only ones. Constitution Day is a great opportunity for all Americans to contemplate the articles and amendments that comprise the legal basis of their republic.