With Americans getting ready to vote, it seems a good time for another post about Zachary Taylor’s and Millard Fillmore’s letters discussing elections. Two years ago I wrote about the process of choosing a president in 1848 and Taylor’s reluctance to seek the White House. But he, Fillmore, and their correspondents had much more to say about elections in general. Some of their concerns mirror those expressed by politicians and citizens today.

For one thing, Taylor wasn’t the only politician who hesitated to run for an office. Candidates’ protests against their own nominations are a recurring theme in the letters. Fillmore, in the years before he joined Taylor’s presidential ticket, resisted fellow Whigs’ efforts to nominate him for statewide office in New York. In 1844, when they promoted him for the governorship, he insisted that they find someone else. In a letter to the politician and journalist Thurlow Weed, published in Weed’s Albany Evening Post on May 21, he announced his “unwillingness” to run “for reasons partly of a public and partly of a private character”—including his lack of “ability.” In a private letter to the former congressman Francis Granger, he was more frank. Fillmore accused his opponents within the party of “killing me with kindness”: they were pushing him as governor, he believed, to keep him away from the vice presidency, which he wanted (Library of Congress). In the end he was nominated as governor but lost to the Democrat.

Three years later, Fillmore again won the Whig nomination for an office he said he didn’t want. His party called on him to become comptroller, New York’s highest financial officer. He swore to State Senator Gideon Hard on September 23, 1847, that his legal business kept him too busy (SUNY-Oswego), but he got the nod anyway. This time he won the election. He grudgingly embarked on its duties, still writing on January 7 to Albert Gallatin, a former US Treasury secretary whom he asked for advice, that he was “too young and inexperienced to rely upon my own judgment” (New-York Historical Society).

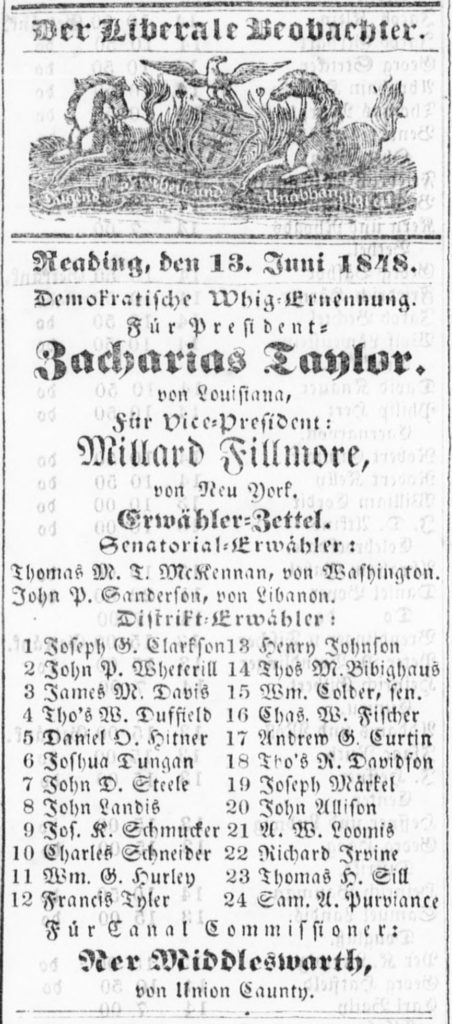

Advertisement for Whig candidates in Der Liberale Beobachter, a German-language newspaper in Reading, PA (Chronicling America/Library of Congress)

In other letters, politicians discussed strategies to win rather than avoid office. Those were largely concerned with getting out their party’s message. As accelerating immigration grew the United States’ diverse ethnic communities, parties needed to campaign in languages besides English. Several of Fillmore’s letters stressed the need to promote Whig candidates in the German-language press. In January 1844 the Whig operative Samuel Lisle Smith put him in touch with a young politician by the name of Lincoln to discuss setting up German newspapers in New York and Illinois (SUNY-Oswego). In New York, meanwhile, although Whigs as a group by no means opposed slavery, they wanted to attract votes from the small minority of White men who did. So Fillmore worked with his colleagues to bring in Cassius M. Clay, a famous Kentucky abolitionist, to speak in towns where he could help.

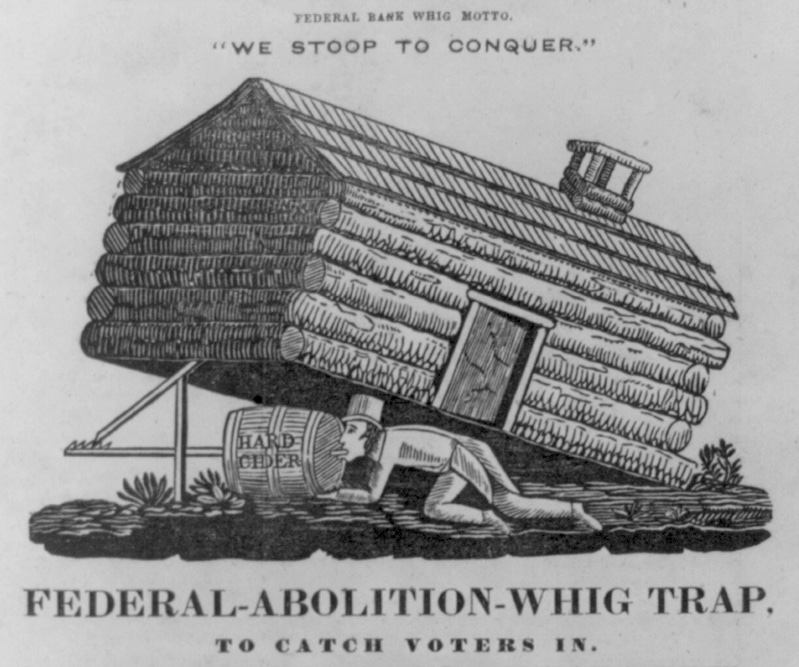

Political cartoon criticizing Whigs for their use of hard cider in the election of 1840 (Library of Congress)

Campaigning wasn’t only about educating voters on a party’s policies. It also involved getting them to the polls, sometimes by unscrupulous or allegedly illegal means. Alcohol, used as a lure by both Democrats and Whigs, was a big part of nineteenth-century election days. The Whig judge Thomas C. Chittenden warned Fillmore on October 29, 1844, that Democrats would make good use of “the productions of the distillery” to bring out voters (SUNY-Oswego). Other Whigs, who paradoxically both courted immigrant voters and engaged in nativism, accused Democrats of winning elections with noncitizens’ votes. Taylor, on February 18, 1848, complained to his son-in-law Robert C. Wood that an “immense influx of foreigners . . . are carried to the polls & are permitted to vote immediately on their arrival, naturalized or not.” Of those, he asserted, “nineteen out of twenty if not more, vote the democratic ticket” (Huntington Library). Unlike today, some states’ laws then allowed unnaturalized White male immigrants to vote, though usually not “immediately on their arrival.”

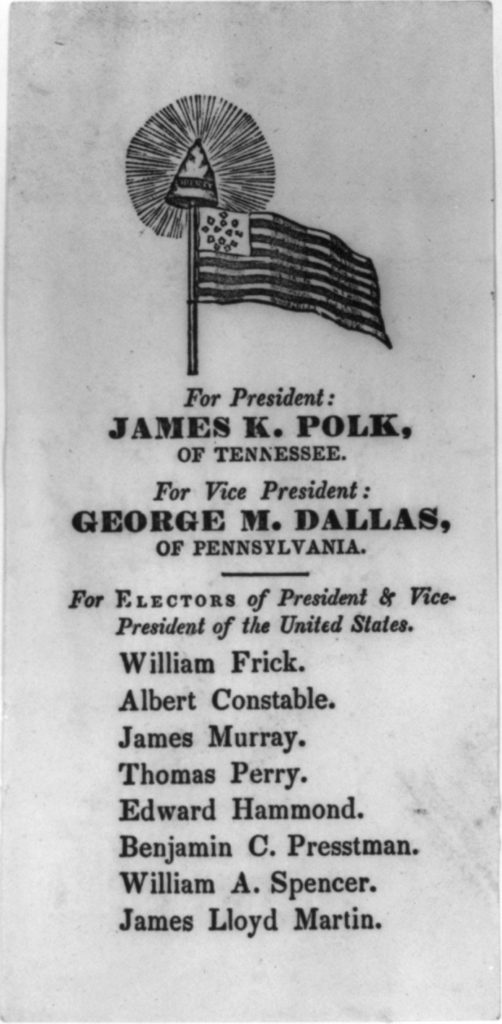

Maryland Democratic ballot from 1844 (Library of Congress)

Politicians also discussed the basic mechanics of voting. Not until the 1880s did US jurisdictions begin printing their own ballots, a protocol adopted earlier in Australia and England. Before then, Americans voted either by voice (as required, for example, by Virginia’s constitution) or, more often, by bringing their own ballots to polling places. Parties and their affiliated newspapers were only too happy to distribute ballots listing their candidates’ names. Fillmore and his allies had to ensure that those were ready and in the correct form. On November 2, 1844, Alexander Kelsey wrote to him frantically that some of the ballots that New York’s Whig Party had printed might not pass legal muster. They needed to be quickly replaced (SUNY-Oswego). One couldn’t vote for Whig candidates if he didn’t have the right ballot in hand.

When Americans show up at the polls this November 8 (or before, for early voting), they can expect to find government-issued print or electronic ballots. Those, unlike the partisan tickets of the nineteenth century, will list all candidates for each office. Taylor, who despite his Whig proclivities often lamented the parties’ control of politics, may have appreciated that change had he lived to see it. In any event, he and Fillmore would surely encourage you, whichever boxes you check off on your ballot, to—shameless plug—click the button on the left side of your screen now and subscribe to this blog.