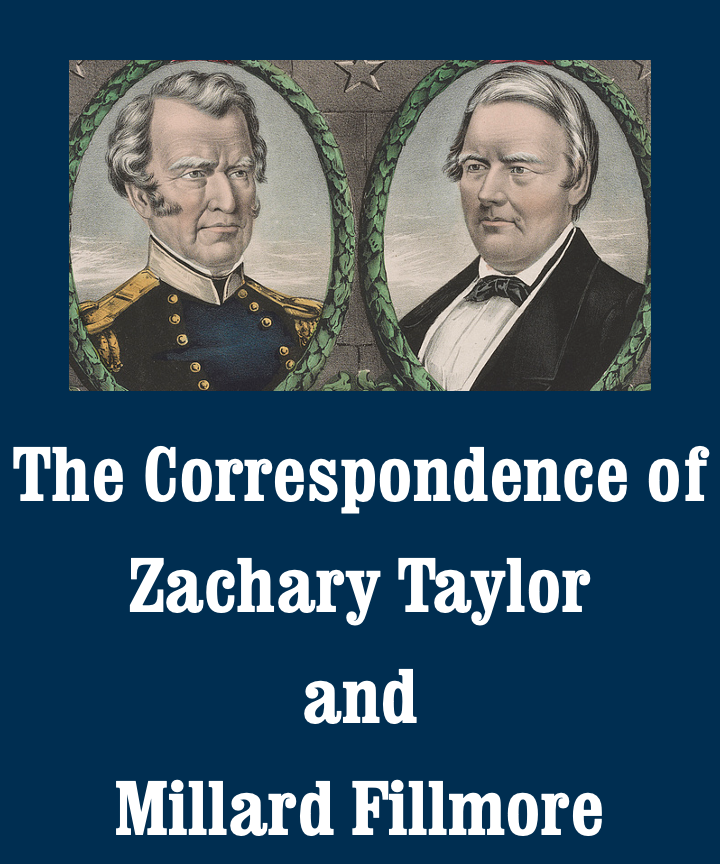

Fillmore doesn’t get much attention in popular culture. He’s appeared in a handful of historically themed films. John McRostie played him in 2010’s Lost River: Lincoln’s Secret Weapon, and Millard (yes, Millard) Vincent played him way back in 1939’s The Monroe Doctrine. A few television shows, including the 1980s classic Head of the Class, have featured schools named for the thirteenth president. But, unlike Lincoln and other chief executives associated with major monuments, he seldom makes it onto either the big or the small screen.

Until, that is, last month. Fans of the world’s most popular answer-and-question show noticed an uncommon category in its March 14 episode. Jeopardy! that day opened with “A Few Moments with Millard Fillmore.” Of the five clues—well, before I go on, in case you missed the show, here’s the clip:

Some may perceive a note of sarcasm in host Ken Jennings’s “oh, exciting” to describe the category, but we choose not to hear that. Fillmore is exciting! And we were excited to help out with a clue. As Ken noted (thanks for the shout-out!) we provided research for the $400 clue about Fillmore’s relationship with Zachary Taylor.

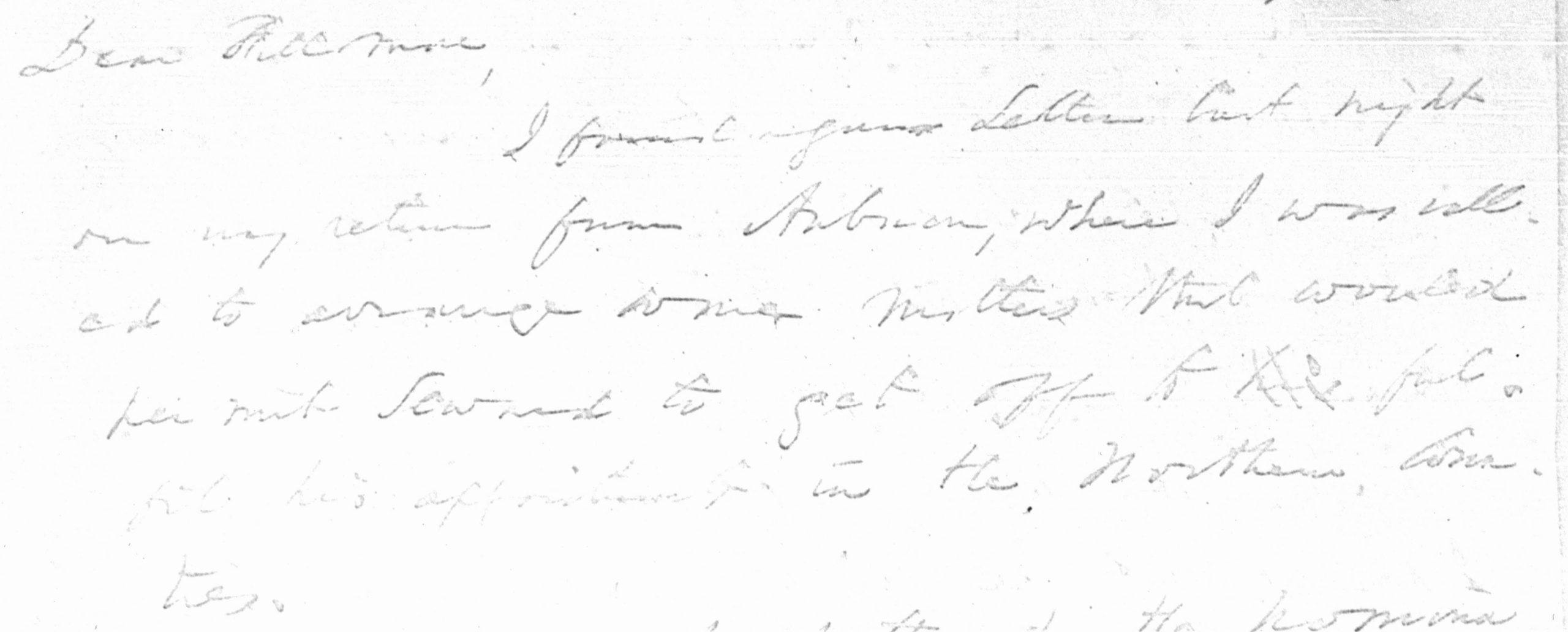

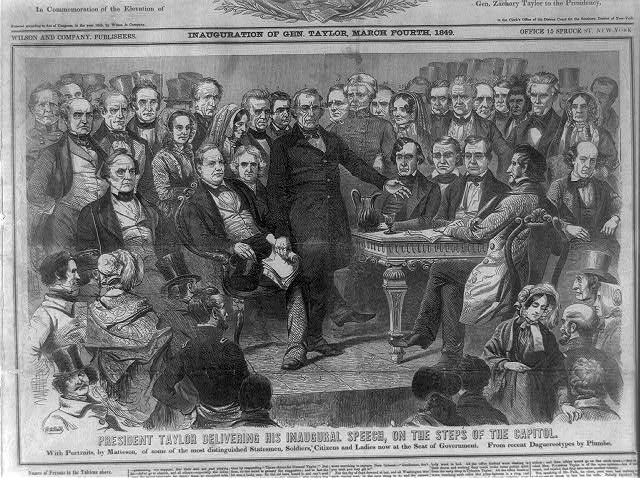

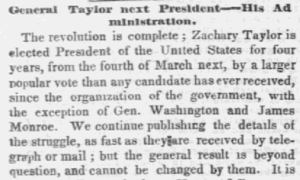

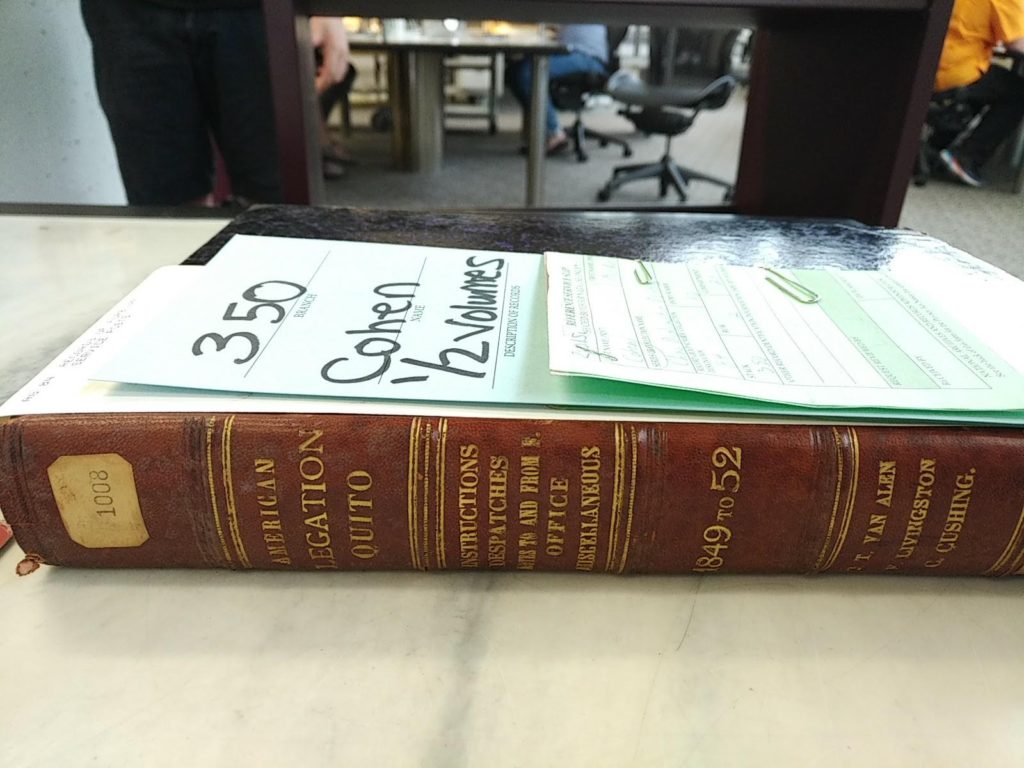

Last fall, Jeopardy!’s writing team reached out to us for information on that relationship and the two men’s correspondence. We explained that, before they were nominated on the same presidential ticket, they didn’t have a relationship. As odd as this may sound today, in the nineteenth century it was common. Party conventions selected vice-presidential nominees to balance their tickets, i.e., to attract voters who might not otherwise support their presidential nominees. That meant choosing someone from a different region, wing of the party, or professional background from the man at the top of the ticket. Hence the Whigs in 1848 nominated a New York lawyer and former congressman to balance a Louisiana planter and army general. That circumstance occasioned Fillmore’s first letter to Taylor, which we shared with our friends at Jeopardy! Our first volume of their letters, in fact, which will document their converging careers from 1844 through the convention, ironically is expected to end with that letter saying, essentially, “We’re running together, so it’s time to introduce ourselves!”

The writers liked the letter, Jeopardy! aired the clue, and the rest is, well, television history. The contestants got every Fillmore clue right (as did I, to my relief), and viewers learned five facts about one of the least known presidents. Here at American University, Adrienne Frank and Andrew Erickson were kind enough to share the project’s brush with popular culture in American, our alumni magazine, along with alumna Kate Kohn’s recent experience as a contestant on the show. AU is making quite the mark on Jeopardy!

That wasn’t even Taylor and Fillmore’s only video appearance this spring. The Institute for Citizenship Studies, at Northwestern Oklahoma State University, was kind enough to invite me to give this year’s Presidential Lecture. Each year the institute invites a researcher to discuss one of the Americans who have served as president. This year the series covered two! On March 22 I headed to Alva, Oklahoma, to discuss Taylor’s and Fillmore’s lives, relationships, policies, and impacts. I thank Aaron L. Mason and Eric J. Schmaltz, directors of the institute, for so hospitably welcoming me. After two years of Zoom meetings, it was a pleasure to hold this in-person conversation with Dr. Mason and to answer very thoughtful questions from NWOSU’s students. For those outside the Alva area, the conversation is now viewable on YouTube. I promise you’ll learn more than five facts from this one. You can also find previous Presidential Lectures on NWOSU’s channel.

On a very serious note, that conversation occurred one month into Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The war and the decisions faced by American leaders made one issue in Taylor’s and Fillmore’s administrations salient. In a different historical context, as I noted in Alva, they had to make similar decisions about US involvement in Eastern Europe.

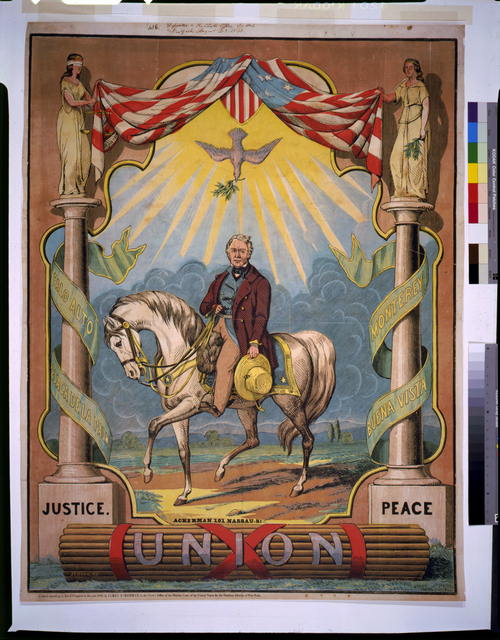

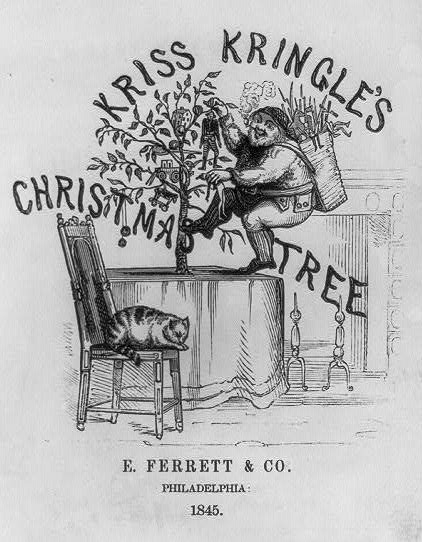

In 1848, a wave of revolutions swept Europe. From France to Poland to the many states of Germany and Italy, people attempted through arguments or armaments either to reform monarchies or to replace them with republics. Americans generally supported their causes, seeing them as emulating the US model of 1776. Officially, though, the US government followed its tradition of noninterference in European affairs.

Then Hungary had its revolution. Long ruled as part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Hungarians fought off the Austrians and, in April 1849, declared their independence under the charismatic governor Lajos Kossuth. Amid widespread American support for the Hungarians’ cause, President Taylor had to choose whether officially to recognize the new government. Willing to do so—and to incur Austria’s ire—only if confident that Hungary would survive, he sent a diplomat to assess the situation. Around the time the diplomat reached Budapest, Austria enlisted Russia’s help in reconquering the rebel nation. Hungary stood little chance against the combined Russian and Austrian armies. The United States did not recognize it, and it soon fell.

Reception of Lajos Kossuth in New York City, December 6, 1851. Lithograph by Nathaniel Currier, 1851. Library of Congress.

Kossuth, though, hoped to reignite the revolution. He sought aid in Europe and the Middle East before, in 1851, crossing the Atlantic. Americans greeted him with dinners, speeches, and parades. Members of Congress and even Secretary of State Daniel Webster celebrated him and his people. But when Kossuth visited the White House, President Fillmore reminded him of this country’s noninterference policy. The US government would not help Hungary in any concrete way. In his annual message to Congress (what we today call the State of the Union) of 1852, he reminded legislators and citizens of George Washington’s insistence that the United States remain neutral. In the 1850s, it was not the world power that it would become. (For more details on Taylor’s and Fillmore’s responses to the Hungarian revolution, see the biographies cited here and here.)

We really do spend most of our time editing Taylor’s and Fillmore’s letters, not lecturing in Oklahoma or chatting with television writers. Opportunities to engage with college students and broader audiences, though, help me to reflect on the guiding aim of the project—to enable historical understanding through primary sources—and on the similarities and the differences between American culture and government in the nineteenth century and today.

Another Whig of the 1840s gained fame later as a Republican. The Papers of Abraham Lincoln Digital Library features four letters from the Illinois legislator and congressman, usually cosigned with others, to Taylor. Among them is

Another Whig of the 1840s gained fame later as a Republican. The Papers of Abraham Lincoln Digital Library features four letters from the Illinois legislator and congressman, usually cosigned with others, to Taylor. Among them is