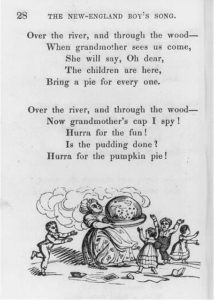

“The New England Boy’s Song about Thanksgiving Day,” in Lydia Maria Child, “Flowers for Children” (Boston, 1845), 28. Library of Congress.

Thanksgiving arrives tomorrow. The holiday, for many of us, brings turkey, stuffing, and pie; this year, it also brings safety measures as we stay home and gather with loved ones by virtual means. At its heart and in its name, however, the day is about the objects of our gratitude. That tradition goes back centuries. Many early U.S. presidents proclaimed a national day of thanksgiving in autumn. George Washington began the tradition on Thursday, November 26, 1789. Thanksgiving became a more official holiday during the Civil War and was fixed as the fourth Thursday in November during World War II.

So I got to wondering: what were Taylor and Fillmore thankful for? Neither proclaimed a national holiday. But both expressed gratitude on behalf of the nation in their annual messages to Congress. Taylor entered office as European nations endured violent struggles between republican revolutionaries and reactionary monarchs. He noted, in December 1849, these “distractions and wars which have prevailed in other quarters of the world.” He concluded, “It is a proper theme of thanksgiving to Him who rules the destinies of nations that we have been able to maintain . . . an independent and neutral position toward all belligerent powers.” Three years later, Fillmore alluded to the cholera pandemic of 1848–49 and to other deadly illnesses. “Our grateful thanks,” he wrote, “are due to an all-merciful Providence, not only for staying the pestilence which in different forms has desolated some of our cities, but for crowning the labors of the husbandman with an abundant harvest and the nation generally with the blessings of peace and posterity.”

Both men also gave thanks in their private correspondence. Most often, they thanked their friends and families simply for writing to them. But our project’s student contributors and I have found more substantive gratitude in the letters, too.

Taylor, at the height of his military career in the 1840s, was grateful for Americans’ support of their troops. In April 1847 he thanked Sarah Moulton Wool, through her army general husband, for her concern about Taylor’s wellbeing. More generally, he praised “her warm & generous hart & kind feelings towards those who peril their lives for their country.” A month later, he announced himself “truly greatful for” several men’s “kind congratulations . . . [on] our successes against the enemy” and their assertion that America “must more than repay us for many of the dangers, toils, & privations we necessarily encounter in the public service.” General Taylor, and surely his subordinate officers and soldiers, appreciated recognition from those back home.

Other thanks followed specific favors and services. Fillmore’s letter about Uncle Tom’s Cabin (as you’ve probably guessed from my repeated mentions of that letter, it’s one of my favorites) begins simply by thanking Susan Greeley for sending the president that antislavery novel. Taylor, who regularly corresponded with the overseer on his Mississippi plantation, thanked Thomas W. Ringgold for sharing good news about himself and the people whom Taylor enslaved. “[I]t was,” he told Ringgold in 1845, “truly gratifying to me to learn you continued to enjoy your health . . . , also that the servants were generally well, & those who had been complaining were for the most part on the mend, which afforded me much pleasure to know.” And Fillmore, after learning that a student debating society at Rutgers College had elected him an honorary member, asked the secretary “to express to the society my grateful sense of this flattering testimony of their respect.”

Many of the letters we’ve transcribed lately have discussed Taylor’s run for the presidency. Much of his gratitude reflected that campaign. As early as October 1847, he offered William C. Bullitt his “sincere thanks” for showing “interest . . . in my reaching the first office is the gift of a great & free people.” But, five months earlier, he shared with a fellow officer his oft-repeated doubts about serving. Should someone else win the presidency, Taylor wrote, he would “be thankful that one more worthy of the office had been found to fill it, & relieve me from even the prospects of embarking in the responsible duties connected with that office.” Perhaps the voters who elected him the next year were thankful for the modesty with which he sought the White House.

Moving on from presidential gratitude, I owe my own thanks. In this blog I often highlight those people, particularly students, who make the Taylor-Fillmore project possible. Please indulge me as I expand those expressions on this week of thanksgiving. Yesterday marked the end of Alyssa Moore’s and Alex Kiprof’s tenures as project interns. Both St. Olaf College seniors, by transcribing letters carefully and accurately yet as quickly as I could send them out, moved the project forward more than I had hoped. I thank them especially for their diligence and enthusiasm despite the challenging environment of COVID-19. Owing to their work and that of the summer’s participants—interns Zoe Golden and Gretchen Ohlmacher and editorial assistant Gab Siegfried—the inaugural year of the Correspondence of Zachary Taylor and Millard Fillmore has been a success. Our corpus of transcribed letters from the pre-presidential years has grown rapidly. Stay tuned for their online publication.

Those essential to the project extend beyond its own staff. Numerous archivists and librarians have helped me to locate letters by or to Taylor or Fillmore. I hesitate to name them only because the list would be long and unfairly incomplete. Every one deserves a shout out. These professionals’ expertise, generosity, and kindness in sharing the historical resources they preserve always earn my gratitude. In today’s world, they are doing so ten times over. As staff have returned to their facilities this fall, after months working at home, they have expanded digital services to enable people such as me to access documents safely and remotely. Moreover, they have done so amid a backlog of service requests from the months the buildings were closed. For this herculean labor, which has brought hundreds of newly scanned letters into my inbox, I give thanks, admiration, and awe.

The project could not operate without generous financial support from both public and private sources. I am deeply grateful to the National Historical Publications and Records Commission, the William G. Pomeroy Foundation, and Delaplaine Foundation, Inc., for awarding it grants this year. I am equally grateful to the Watson-Brown Foundation and the Summerlee Foundation for announcing grants to the project for next year. My colleagues and I are honored to partner with these organizations in making primary sources widely accessible.

Finally, I thank those here at American University who have supported and built this new project. Colette AbiChaker and Dave Marcotte, in the Washington Institute for Public Affairs Research; Stephen Petix, in the Office of Sponsored Programs; Sam Alarif, in Grants and Contracts Accounting; Heather Kirkland and Adam Whitehurst, in the School of Public Affairs (SPA); Edith Laurencin, formerly in SPA; Hannah Purkey, in the Center for Congressional and Presidential Studies (CCPS); Becky Prosky, formerly in CCPS; James Helms, in the Department of Government; and Chay Rao, in Strategic Communications & Public Relations, all have worked hard to get the project up and running and to continue its success through this and into next year. Most of all, I thank David Barker, director of CCPS and executive director of the project, for inviting me to launch it at CCPS and for enthusiastically supporting and promoting it ever since. I am delighted to be locating and publishing the letters of these two presidents in such a perfect institutional home.