Zachary Taylor has become an unlikely symbol of the attack of January 6 on the U.S. Capitol. In an attempt to overturn the result of the presidential election, Americans forced their way into the seat of the federal government. They assaulted police and threatened the lives of the vice president and members of Congress. One police officer, allegedly assaulted by two men, died of strokes the next day. The rioters also damaged works of art. Grotesquely, someone smeared a red substance on a bust of the twelfth president. Capitol staff have since wrapped it in plastic, but commentators including journalists and an art historian have drawn public attention to Taylor’s apparently bloodied face.

The targeting of Taylor is meaningful. True, the perpetrators may not have known whose image they were defacing. Few people today would recognize him. Still, intentionally or not, they singled out a president who himself had struggled over whether to challenge the peaceful operation of government. As a general and as commander-in-chief in the 1840s and 1850s, he swore allegiance to the Union. Yet he also contemplated the need to disrupt that Union with violence.

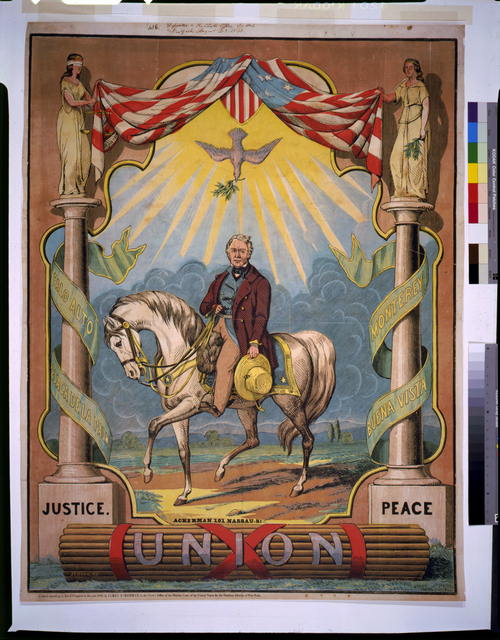

Taylor campaign poster, engraved by Thomas W. Strong, 1848 (Library of Congress)

Imagine this scenario. It’s 1847. General Taylor has won enormous popularity from his army’s victories in the Mexican-American War. He concludes that the American people want him to become president. He sends subordinate officers around the country to confirm that. Assured that the majority do prefer him over the incumbent, James K. Polk, he decides not to wait for next year’s election. He simply marches to Washington and takes over the government.

No, that didn’t happen. When Maris B. Pierce, a Seneca Indian chief and lawyer, described these hypothetical events in a February 1849 letter to Polk, he presented them as an absurdity. U.S. law would “[c]ertainly not” recognize such a coup as “a ligitimate change of Government.” Furthermore, Pierce might have added, Taylor never would have attempted it. He revered the Constitution and recognized that changes in the administration must follow legitimate elections and peaceful inaugurations.

Yet, in that era, violations of U.S. legal principles were not unthinkable. Pierce contrasted the absurdity of a Taylor coup with what he saw as the reality of a Seneca one. A group of New York Senecas, in 1848, had decided to replace their traditional government of hereditary chiefs with one of elected officials. The Polk administration quickly had recognized the latter. Pierce, one of the ousted chiefs, argued that in doing so, the U.S. government undemocratically had accepted the assertions of a dissatisfied minority over both established law and the wishes of the majority. If Taylor couldn’t launch a coup, why could those Senecas? Pierce, however logical, failed to sway President Polk.

Threats to U.S. law extended beyond Indian relations. We often hear that, in our time, Americans are more divided than they have been since the Civil War era. The benchmark is apt. After the United States annexed western lands from Mexico in 1848, White Americans sharply split over whether to expand slavery into the region. While Democrats and Whigs continued to fight across party lines, Northerners and Southerners increasingly fought across regional ones. Those fights were not always verbal. Long before the actual Civil War, and even absent a coup like the one Pierce imagined, violence was becoming a common feature of U.S. politics. Last week, at a virtual conference celebrating the completion of the John Jay Papers (congratulations to our fellow editors there!), I had the pleasure to hear a keynote lecture by the historian Joanne B. Freeman. Author of two books on political violence, Freeman noted both the riots common to polling places in the 1850s and the brawls that broke out in the halls of Congress among impassioned, intoxicated, and armed politicians.

Americans understood that law, peace, and the Union itself were in danger. In 1850 Andrew Lane, who lived in Connecticut but owned slaves in (probably) Louisiana, published a letter to the president warning what would happen if slaveowners did not get their way. He predicted a division of the states, through either peaceful separation or all-out war, with New England becoming a free republic and the rest of the country continuing to enslave Black Americans. Fillmore himself, as I have noted before, wondered in the White House “whether this ever-disturbing subject may not rend this Union asunder” through a “war of races.”

Taylor’s own musings on slavery and disunion are fascinating and, frankly, shocking. He is often quoted (well, insofar as one can say Zachary Taylor is “often quoted”) as vowing while president to command troops himself against any Southern rebels and to “hang them with less reluctance than he had hung deserters and spies in Mexico.” The quotation, published a quarter century later by political boss Thurlow Weed and disputed by other supposed witnesses, is dubious. The firmly unionist sentiment, though, is likely accurate, and the language of violence certainly fit the times. President Taylor, it appears, had no patience for those who would break the United States’ laws and overturn its political processes.

But that was President Taylor. Before he took office, he expressed more nuanced views. On one hand, he worried about the country’s future. As he told his brother in January 1848, he feared “the slave question, . . . if not speedily arrested will lead to great confusion, if not to disunion.” On the other hand, he revealed privately that he might support such a move. An August 1847 letter to his son-in-law, the future Confederate president Jefferson Davis, startled both transcriber Gabriella Siegfried and me. Taylor lamented Americans’ inability calmly to discuss their differences, particularly over slavery: “the moment any thing of the kind is attemp[t]ed, men appear . . . to lose their temper as well as their reason, . . . only adding fuel to the flames, & to widen inste[a]d of healing the breach between the parties.” He hoped sober debate would resume. But if antislavery Northerners argued too fervently, he contended, “let the South act promptly, boldly & decisively with arms in their hands if necessary, as the union in that case will be blown to atoms, or will be no longer worth preserving.” This future president, later celebrated as a staunch unionist, was contemplating a violent breakup of the republic.

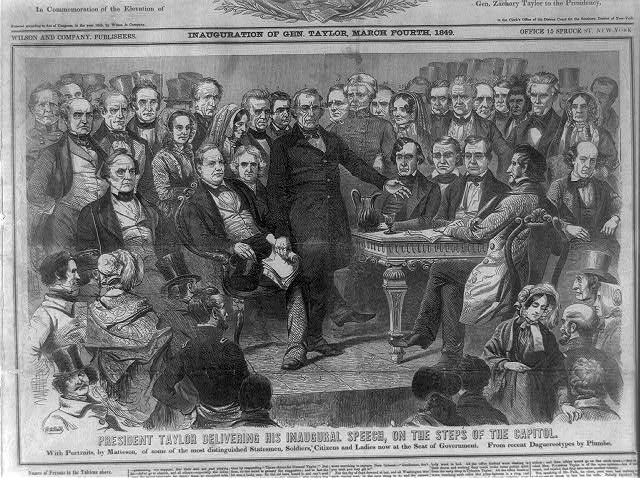

Taylor’s inauguration, engraved by W. W. Butt, 1849 (Library of Congress)

Fortunately for Taylor’s election prospects, that letter did not become public. Once he become president, he seems to have grown less tolerant of proslavery disunionists and more so of antislavery Americans. In his inaugural address, he called for “attempts to assuage the bitterness which too often marks unavoidable differences of opinion” and urged on Congress “such measures of conciliation as may harmonize conflicting interests and . . . perpetuate that Union which should be the paramount object of our hopes and affections.” Henry Clay Preuss, in a poem celebrating Taylor’s inauguration, likewise called for unity:

Whigs, Democrats, all—oh! why should ye pause,

As brothers of one common band

To join heart and hand in this glorious cause,

And drive party strife from our land.

(“For Taylor and Millard Fillmore!” [1849?], SUNY–Oswego)

When I launched this blog last spring, I did not intend to engage so directly with events of today. I aimed to spread word of the Taylor-Fillmore project’s progress, to share some of our findings, and to promulgate knowledge of antebellum America. Those remain my goals. But life has drawn links between now and then that I cannot ignore. The past year has seen a global pandemic, racial debate and violence, a heated presidential election, and political strife that prompted President Joe Biden to plead in his inaugural, “disagreement must not lead to disunion.” All that, with just Taylor’s slightly different phrasing, was also true of 1848–49. Now 2021 has even put Taylor’s bloodied face on the newspapers. History never quite repeats itself, nor does it present a simple blueprint to guide our actions. But I hope that, by assembling and publishing primary sources, we documentary editors can enable a deeper understanding of the past to inform all who contemplate America’s present and future.

To end on a happy note, I have two announcements. First, you now can subscribe to this blog! Enter your email address in the field on the left (in the drop-down menu if you’re using a phone or tablet) to get an announcement each time we post a new entry. Second, this month Cameron Coyle joined our project as a volunteer. A high school senior (and recently admitted to Yale—congratulations!), Cameron is founder and director of the Zachary Taylor Project. He educates about Taylor on its website and hopes to establish a Taylor historic site. With his enthusiasm for preserving history and talent for transcribing letters, I’m glad to have him aboard.

Note: An earlier version of this article asserted that rioters on January 6 had murdered a police officer, as was initially proposed by investigators. A medical examiner has since concluded that Officer Brian Sicknick died of natural causes, and the article has been updated.