Click above to listen to this article, read by Kate E. Hutchinson.

We at the Taylor-Fillmore project have something to celebrate. We just completed the manuscript of the first volume of Zachary Taylor’s and Millard Fillmore’s letters. Editors and student contributors transcribed and annotated 376 documents written by or to those powerful but little-known figures in nineteenth-century America. They stretch from 1844, when the United States was preparing to annex Texas, to mid-1848, after it had acquired half of Mexico. Now we will work with the publishers to finalize the print and digital volume. You’ll be able to read the letters, at your library or on your computer, next summer. We thank all who have made this possible, including the National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC) and our other sponsors committed to expanding readers’ access to original historical documents.

Two weeks ago, I got to share that good news with the folks at American POTUS. They kindly invited me to join their podcast about US presidents. My conversation with host Alan Lowe about Taylor and Fillmore is now available on the American POTUS website, on our website, and pretty much wherever you get your podcasts.

Now, let’s discuss bigger celebrations.

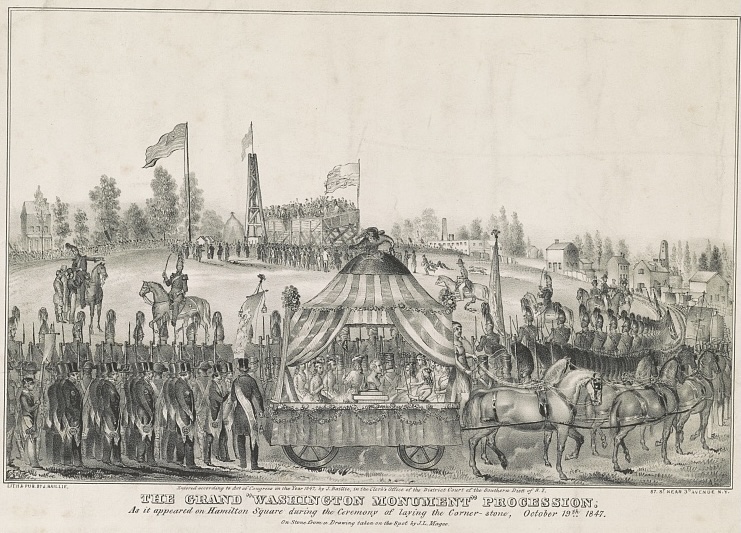

Washington Monument cornerstone-laying procession, lithograph by James S. Baillie, 1847 (Library of Congress)

In 2026, the United States will commemorate its semiquincentennial: the 250th anniversary of its founding. All states and territories have established commissions to mark the occasion. At the federal level, Congress created the US Semiquincentennial Commission in 2016, and President Donald J. Trump issued an executive order creating Task Force 250, with him as chair, this February. Private organizations ranging from the Organization of American Historians to Black America 250 have assembled educational materials tied to the anniversary. I sit on the Semiquincentennial Committee of the Association for Documentary Editing, which aims to focus attention on key documents from the full span of US history. Commemorations will culminate next summer, when we reach 250 years after the adoption of the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776.

In the meantime, Americans have celebrated other specific anniversaries. This April 19 was the 250th of the Battles of Lexington and Concord, which launched the US Revolution. May 10 was the 250th of the convening in Philadelphia of the Second Continental Congress. And this Saturday will be the 250th birthday of the US Army. On June 14, 1775, the Second Continental Congress passed a resolution creating ten companies of riflemen and designating the colonists’ military organization “the American continental army.” It, under General George Washington’s command, became the official seed of the armed forces in which brave men and women have served their country in the two and a half centuries since.

A festival and parade in Washington, DC, will form the centerpiece of the national celebration of the army and of servicepeople past and present. The Association of the United States Army will hold another parade and related events in Philadelphia. By a historical coincidence, these happen to fall on Flag Day (precisely two years after creating the army, Congress adopted the Stars and Stripes). By another coincidence, they fall on President Trump’s seventy-ninth birthday (discussion of the commemoration began years ago, though the specific plan for a parade emerged this spring).

These political and military anniversaries got me thinking—as I tend to do—about Zachary Taylor and Millard Fillmore. As we’ve worked through their letters, we’ve come across discussions of anniversaries, military tributes, and, yes, parades. This seems a good time to share what types of celebrations they and their correspondents witnessed and what those Americans of an earlier era thought about marking dates on the calendar and honoring soldiers in the field.

As in the 2020s, Americans in the 1840s celebrated national anniversaries. Although no major ones arose in that decade—the nation’s seventy-fifth did in 1851, but our project hasn’t gotten there yet—Independence Day came each year. I wrote a little about that holiday earlier in this blog.

Some politicians used July 4 for partisan ends. In 1844, supporters of the Whig Party invited Fillmore to their festivities in Rushford, NY. He responded that he already had committed to attend an event elsewhere “on the anniversary of the Birth day of our nation.” But he took the opportunity, in his response, to equate the colonists who had rejected British rule—known in their time as “whigs”—with his nineteenth-century party: “The whig spirit of ’76 gave us Independence & freedom and the Whig spirit of 1844 must maintain that independence and freedom, or the blood of the Revolution was poured out in vain.”

Fillmore’s letters more often discussed celebrations planned for purely political, not commemorative, purposes. In August 1844, Whigs invited him to a “MASS CONVENTION” in Seneca Falls, NY. Beginning with a “procession” complete with “Banners and Music,” it promoted Henry Clay’s candidacy for the White House and the party’s support for a high tariff and opposition to annexing Texas. Four years later, Amos Brown wrote to Fillmore recounting Democratic presidential nominee Lewis Cass’s arrival home in Detroit. After “two brass pieces fireing” at the wharf, where Cass’s steamboat landed, he went to his house with a “possession [procession] which . . . consisted of a band of music five carriages one buggy and one too horse wagon and betwene one and two hundred fo[o]tmen in al the company about the house encluding locoes [i.e., Democrats] whigs and boys and in the possession there might have been one thousand.”

Around Taylor, who spent most of this time commanding troops in Texas and Mexico, festivities honored his army. He was not always happy about that. By the end of 1845, as Texas was becoming a state and his forces were defending it against Mexico and Indigenous peoples, he had tired of both the monotonous work and the noisy entertainment. He wrote to his daughter Mary Elizabeth, on December 15, about the “constant employment . . . what with instruction, mounting guards, reviews &c.” He acknowledged that “fine bands & excellen field music has made the pass tolerably rapidly; but,” he added, “all the pomp & parade of such things are lost on me, I now sigh for peace & quiet with my family around me-”

Later, when Taylor returned home as a presidential candidate, he developed mixed feelings about the political festivities to which he was constantly invited. He told Orlando Brown, on March 15, 1848, that he would have enjoyed visiting Kentucky at the state legislature’s invitation, seeing “many old & long cherished friends, all of whom I should have been delighted to have met.” But he was still an officer in the army (he didn’t resign until three months after his election). He worried that opponents would accuse him of spending his leave of absence “traveling about the country for eletioneering purposes; I therefore deemed it most prudent to decline all such invitations” (Kentucky Historical Society).

His reluctance to travel to celebrations, while at least partly rooted in political calculation, may also have accorded with his limited view of the presidency. Candidate Taylor determinedly refused to share his political opinions and argued that even a sitting president’s opinions “are neither important nor necessary” (ZT to Unknown, March 29, 1848, in Washington Daily Union, October 14, 1848) in a country where Congress took precedence in setting policy. Keeping out of the electoral limelight, perhaps, fit his electoral platform.

Taylor firmly supported, however, honoring the men with whom he served. He may not have loved “all the pomp & parade,” but he did not deny it to the officers and soldiers in his army. He also welcomed civilians’ recognition of the hardships that military personnel endured. He often wrote, as he did to Jefferson Davis on July 27, 1847, of “our young gallant respectable volunteer soldirs, who have volunteered in the cause of their country, who are daily falling victims to the hardships, privations &c common to a soldiers life, & to the diseases that accompany the march . . . under a tropical sun.” He appreciated written expressions of gratitude for their sacrifices.

Taylor also gratefully read about the “illuminations”—the lighting up of public and private buildings—organized in US cities to celebrate victories in Mexico. He wrote to Robert C. Wood, likely on June 4, 1847, “The brilliant illuminations in New Orleans, & elsewhere on acct. of the success of our arms, shewes that our Citizens duly appreciate the labors, privations & dangers encounted in the publis servants by those employed by them, which demonstations of respect & gratitude must be consoling in some degree to those who have lost relatives, health & friends during this contest” (Huntington Library). Those visual displays were not overseen by the national government. But Taylor and, presumably, many other officers, soldiers, and family members took heart from the local expressions of understanding and support.