Library of Congress.

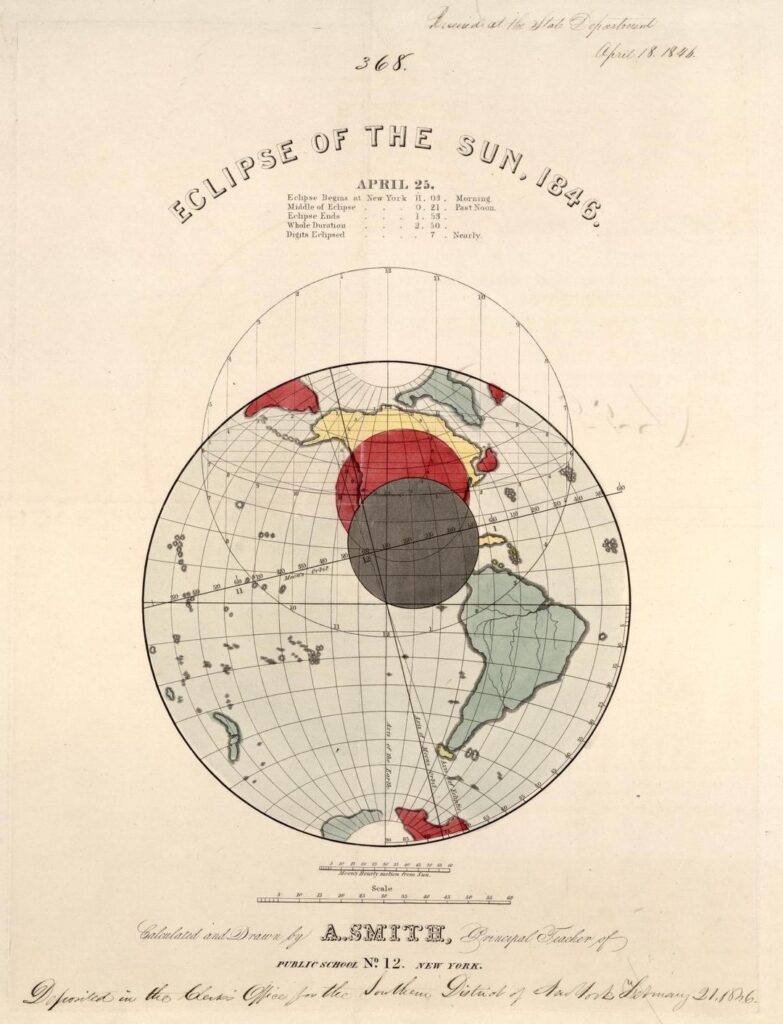

April 25, 1846, was a dark day in North American history. Literally. On that day, the moon passed directly between Earth and the Sun. Some Caribbean islands experienced a total solar eclipse. Much of Mexico and the United States got a partial one. As on April 8, 2024, the sky’s light was blotted out.

But that was not all. For those who cherished peace, April 25 was also a dark day in a figurative sense. Near the shore of the Rio Grande, in territory disputed between the two countries, Mexican troops surrounded and fired on US ones. On that dark day, the Mexican-American War began.

With the occasional break for astronomical phenomena, much of the news today centers on international violence. Most prominent are the wars between Ukraine and Russia and between Israel and Hamas. This emphasis is not new. Both news cycles and historical eras have long been defined by wars. Historians of the United States, for instance, divide their timeline into the Revolutionary Era, the Civil War Era, the Cold War Era, and suchlike.

That periodization makes me think about our project’s place in the span of US history. We are editing letters written between 1844 and 1853. That decade was part of what historians usually call the antebellum period, meaning the period before the war. The label is accurate, as both the chronology and the letters reflect. Americans fought the Civil War eight years after Millard Fillmore’s presidency. His and Zachary Taylor’s letters, including some that I’ve quoted in this blog, express fears or threats of such a conflict.

But our decade wasn’t just before a war. The United States, from 1846 to 1848, was at war. In addition to the numerous violent struggles with Indigenous peoples whose land White Americans coveted—struggles in which Taylor had built his military career—these years revolved around the Mexican-American War. Given how central it was to Taylor’s life, and how central it will be to our first volume of letters—which is rapidly approaching completion—it seems high time to devote a blog entry to it. Regular readers of the blog, and users of our teaching guide, already know parts of the story. Today I want to highlight some tragedies and dilemmas of war that, though in different forms and contexts, persist across space and time.

It started with Texas. In 1821, Mexico won its independence from Spain. One of the new nation’s states was Coahuila y Tejas. White Americans soon began immigrating into the part of it that they called Texas, often bringing enslaved African Americans and setting up cotton plantations. Mexico’s closing the border in 1830 did not stop them from immigrating illegally. In 1836 US expatriates outnumbered Mexicans in Texas, controlled its government, declared its independence, and asked the United States to annex it. The US government hesitated, fearing that annexation would anger both Mexico, which still claimed Texas, and Northern US Whites, who resented the political power of Southern enslavers. Interested parties did not even agree on how much hitherto Mexican territory Texas included. But in 1845, at the insistence of Presidents John Tyler and James K. Polk, the United States admitted Texas as a state, come what might.

Those anticipating Mexico’s anger had been right. As far as its government was concerned, the United States had no right to annex Mexican Texas. And it had even less right to annex the land southwest of the Nueces River and northeast of the Rio Grande, which Polk claimed was included in the deal but which Mexico denied was even part of Texas. Both nations prepared for war. Under orders from Washington, General Taylor led troops into Texas in 1845 and to the Rio Grande in 1846. On April 25, Mexican troops ambushed a US scouting party at the Carricitos Ranch, just north of the river. Eleven Americans died, and the war had begun.

Joel Dorman Steele, A Brief History of the United States (New York: American, 1885). Private collection of Roy Winkelman/Florida Center for Instructional Technology, University of South Florida, https://etc.usf.edu/maps.

I won’t give all the details here. You can read them in narratives of the war by historians such as K. Jack Bauer and Amy S. Greenberg—or in the letters by Taylor and his contemporaries when our volume comes out. To summarize, though, in 1846 and 1847 Taylor commanded at battles near the Rio Grande while General Winfield Scott led an invasion of southern Mexico that culminated in the capture of Mexico City. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed on February 2, 1848, ended hostilities and transferred half of Mexico’s territory—everything from Texas to California—to the United States. Taylor’s military success made him a national hero, leading to his election as, well, you know. Debate over whether to extend slavery into the new US possessions escalated the debate over slavery, eventually leading to Southern secession and, well, you know.

When mentioning the war in earlier blog entries, I have noted its connections with race, constitutionalism, and electoral politics. But Taylor, Polk, and their Mexican counterparts also faced other questions as they determined and executed war policy. Those included questions prominent in the wars on our televisions today.

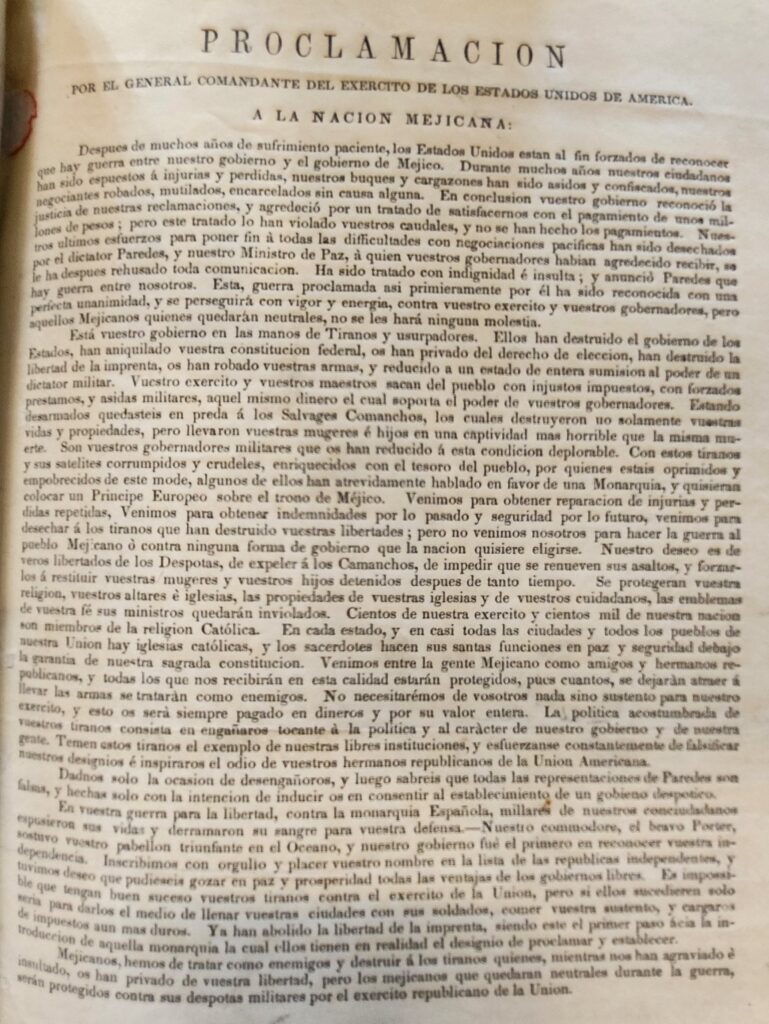

For one, what role would religion play? The United States, a majority Protestant nation, was fighting (invading, from the Mexican perspective) an officially Catholic one. With many native-born Americans resentful of Catholic immigrants, people in both countries wondered if the United States would use this war to weaken or overthrow the Catholic Church in Mexico. The Polk administration tried to quash that speculation, to some nativists’ dismay, appointing Jesuit priests to accompany the army and ordering Taylor to proclaim in June 1846 that Mexicans’ religion and Church property would be protected. “[W]e come to overthrow the tyrants who have destroyed your liberties,” the Americans explained, “but we come to make no war upon the people of Mexico.” (Copies of the proclamation, in Spanish and English, are at Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, the Huntington Library, and the National Archives.) Some Mexicans remained unconvinced. The Mexican revolutionary Hilario de Mesa told Taylor on February 2, 1847, of his compatriots’ concerns that their northern neighbors would attempt “the entire conquest of Our race, [and] of our religion” (National Archives).

National Archives, Record Group 287, file code 29A–E1.

Whatever their policies, neither civil nor military authorities could control every soldier. Taylor’s letters are littered with reports of and frustrations over war atrocities. A series of crimes that particularly irked him began when US volunteers near Agua Nueva raped several Mexican women on Christmas Day 1846. Retaliatory murders of US soldiers and Mexican civilians led to an investigation by Taylor and other officers. Unable to identify the guilty men, Taylor punished their entire companies. On February 18 he told Eduardo Gonzalez, a local Mexican politician, “those outrages could not have caused you a deeper regret than it did myself.” Citing “the interests of humanity,” he expressed a determination “to punish them as severely as the laws will permit” and to “prevent . . . such scenes in future.” He added, however, that in other instances Mexicans had attacked or killed US soldiers “without provocation” (National Archives).

Taylor also corresponded regularly with Mexican leaders about prisoners of war. After the US surrender at the Carricitos Ranch, the Mexicans incarcerated nearly the entire US scouting party. When Taylor’s forces captured cities, such as Monterrey in a major battle in September 1846, they likewise took prisoners. After each such event, the commanding officers discussed whether, when, and how to exchange POWs. Both sides wanted their people back, but ironing out the details sometimes required a long exchange of letters. Those details sometimes extended beyond the release of captured soldiers. Francisco de Paula Morales, governor of Nuevo León, wrote to Taylor on September 23 that poor families in Monterrey had lacked the resources to leave before the battle. He asked Taylor either to let them evacuate or to order US troops to “respect” them. Taylor, answering the same day, chose the latter but with a caveat: “the rights of individuals, who are not hostile, particularly women and children, will be respected as much as is possible in a state of warlike operations.” (Morales’s letter is in the National Archives; Taylor’s was published in the Washington Daily Union, Nov. 10, 1846.)

Given the privations and tragedies faced by those living amid the Mexican-American War—both soldiers and civilians—it is perhaps unsurprising that the lifelong officer Taylor often yearned for peace. He wrote to Congressman Truman Smith on March 4, 1848, “I am a peace man, and . . . I deem a state of peace to be absolutely necessary to the proper and healthful action of our republican institutions” (Morning Courier and New-York Enquirer, Aug. 2, 1848). Once he became president, he was surely happy to report in his Annual Message to Congress (what we today call the State of the Union Address) on December 4, 1849, that “We are at peace with all the other nations of the world.” The claim was an exaggeration, given the continuing violent removal of Indigenous peoples. From his perspective, though, a brighter day had dawned.