What do people talk about the most? Sports? Politics? Literature? I don’t know about you, but I find that one of the most common topics to come up in work and social conversations, at least briefly, is the weather. It may be forest fires in the American West, a hurricane in the Southeast, drought in the Midwest, or merely the hope for a sunny day.

This is nothing new. Although we don’t know the content of most historical conversations, we do know what people of the past wrote down. In their diaries, journals, and letters, they, too, often discussed the weather. Henry David Thoreau famously recorded conditions in Concord, Massachusetts. His detailed journals, which scholars are editing and publishing, have helped biologists track climate change from the 1840s to the 2000s. Figures often linked with politics, including George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and Benjamin Franklin, also commented on the weather in their diaries. Those observations, scattered throughout the manuscripts and the published editions of those men’s papers, have been assembled in an open-access climatic dataset by the National Centers for Environmental information. Historical Americans, like us, loved to talk about (okay, write about) the weather.

Zachary Taylor, Millard Fillmore, and their associates were no exceptions. They, especially Taylor, regularly shared local weather conditions and the consequences of regional climates in their letters. Sometimes they did so merely in reference to the feasibility or enjoyability of social visits. On March 10, 1844, Fillmore lamented to Elizabeth Milligan that friends had been unable to visit him in Buffalo recently due to “little or no sleighing here” at a time of year when other forms of transportation came to a halt. Eight days later, his cousin Ann L. Dixson invited him and his wife Abigail to visit that summer, “the most pleasant season” in her home of Ebensburgh, Pennsylvania. That June 10 Joseph C. Luther, a U.S. diplomat in Haiti, complained to his friend Fillmore of the heat in that island nation. (These three letters are on the microfilm Millard Fillmore Papers.)

Lithograph by O. Knirsch, published by Currier & Ives, 1853. Library of Congress.

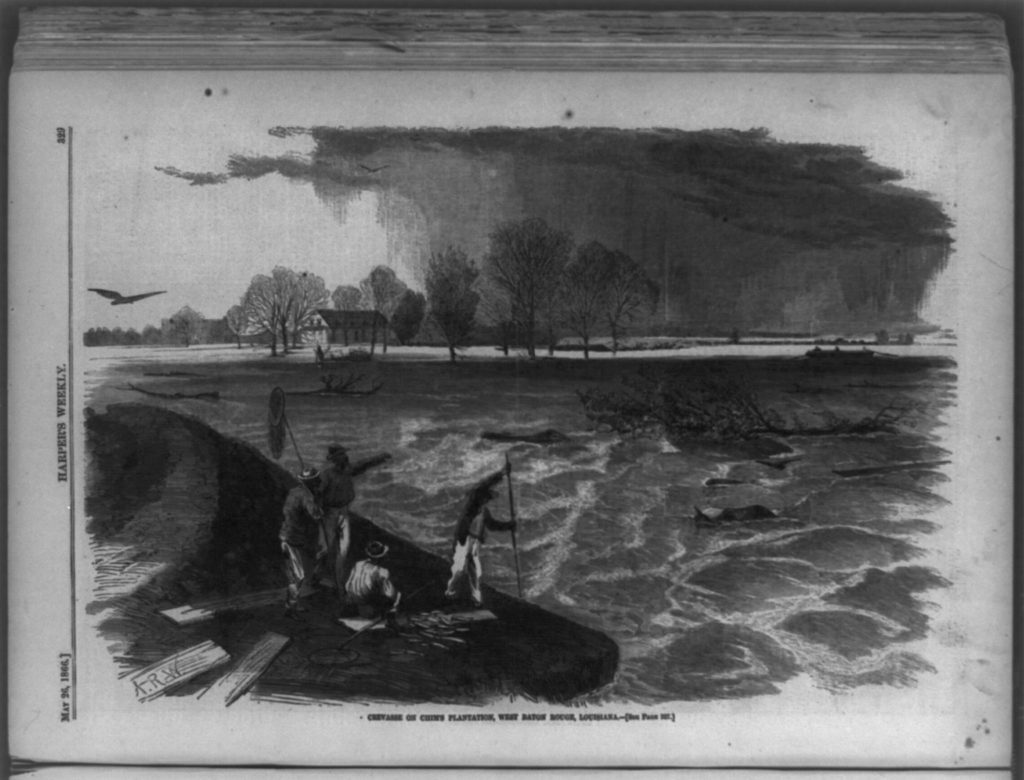

More often, in the letters, the weather influenced people’s lives or livelihoods. Taylor, on December 16, 1845, expressed concern to overseer Thomas W. Ringgold that the enslaved people on Taylor’s plantation “have not been able to do much in the way of picking cotton, as it has been unusually wet & remarkably cold for the season & climate.” Recognizing the weather’s impact on their ability to harvest crops, he suggested other tasks, such as felling trees to build a bridge and fences, if the temperature stayed too low. A year and a half later, he wrote to his brother Joseph with a more serious concern about the plantation: it had flooded. “[M]y worst apprehensions,” he lamented, “have been more than realized.”

Flooded plantation in Louisiana, in Harper’s Weekly, May 26, 1866, 329. Library of Congress.

Weather, the medical authorities of the day recognized, also influenced health. Doctors urged those recovering from illness or injury, in particular, to travel to favorable climes. In September 1847 Taylor, having learned that some of Joseph’s children suffered from whooping cough, shared his brother’s hope that, “as you say the weather was favorable, . . . they would soon recover.” The following July he reminded Jefferson Davis of the northern states’ “reputation for restoring invalids from the South” and advised that Davis’s ill brother “ought to go North every season, as the preservation of his health & life is of more importance to his family friends and country than all the wealth he could accumulate for the former.”

Taylor, however, most often wrote about the weather in reference to its challenges to the army units he commanded. On July 17, 1844, he asked Adjutant General Roger Jones to send more medical officers to support the troops in and around Louisiana’s Fort Jesup. Both the possibility of battle and “the approaching sickly season,” he stressed, produced a need for medical care. Two years later, during the Mexican-American War, he told his son-in-law Robert C. Wood that “[i]n a climate like” that on the Rio Grande, “there must be a great deal of disease, which as a matter of course must result in some deaths, & we will be fortunate indeed if no contagion gets among us that does not carry off hundreds.” His superiors in Washington, though not attentive enough to the army’s needs for Taylor’s taste, appreciated the importance of weather to the campaign. “Much apprehension,” Secretary of War William L. Marcy wrote him in June 1846, “is felt as to what is called the unhealthy season.” He told Taylor what the general knew well: that “[y]our positions should have a particular reference to” the weather and associated diseases in the regions of northern Mexico. Weather in the nineteenth century, as in the twenty-first, helped shape life, death, and the actions of governments.

The Taylor-Fillmore project has had a sunny and productive summer thanks to the contributions of students to our work. Alaysia Bookal, a graduate student in American University’s School of Education and School of Public Affairs, is our editorial assistant this summer. Annika Quinn, a senior at St. Olaf College majoring in history and Asian studies, is our intern. Both have done excellent work toward bringing these primary sources to students, scholars, and the public.