God Save Poland: Political Nationalism and Wajda’s Afterimage

by Katherine Wurst

The refrain of Boże, coś Polskę (God save Poland), when first written in 1816, read “Save our King, Lord!” This solemn prayer for the nation praised Tsar Alexander I, who became the ruler of the new Kingdom of Poland following the defeat of Napoleon. In 1830, the refrain changed: “Return our Homeland to us, Lord!” Where the first rendition cried support for the Russian Empire, the second begged for independence lost so many years ago after the failures of the November Uprising. It was not until over a century later, in 1989, that the hymn was once again revised. Uniquely, the change in wording also represented a shift within the tone of the country. The same year marked the official end of the Polish People’s Republic (PPR), the one-party socialist system implemented by the Soviet Union following World War II. From 1952 up until that point, democracy was a struggle. A time of oppression, censorship, and famine scarred the lands of Poland which had been occupied and manipulated so many times before. The Solidarity Movement, however, challenged the Soviet Union and, through planned strikes and powerful rhetoric, defeated martial law and paved the path for the formation of a new governmental system. The freedom which Poles had never experienced before gave them good reason to sing, “Bless our Homeland and freedom, Lord!” and, in 1996 after the certification of a true democracy, “Bless our free Homeland, Lord!” (Trochimczyk).

Poland’s complex and troubled history has created a very unique culture within modern-day Polish society. It is clear, like within Boże, coś Polskę, that the oppression faced under Soviet rule traumatized Poles in almost all aspects of life. There are many living today who experienced the restraints of the PPR, showing just how recently these scars of society were created. One would assume that such a horrible era in history would be abandoned and works of art, among other things, would avoid recreating it. In contrast, there seems to be an obsession of historians and artists alike to relive the era of communism in a way that fuels Polish nationalism. Mainly, this method uses storytelling to emphasize the violent and evil aspects of Russians versus the victimized yet strong-willed aspects of Poles. This trend appears in everything from paintings to historical fictional novels, but often is portrayed most powerfully within film.

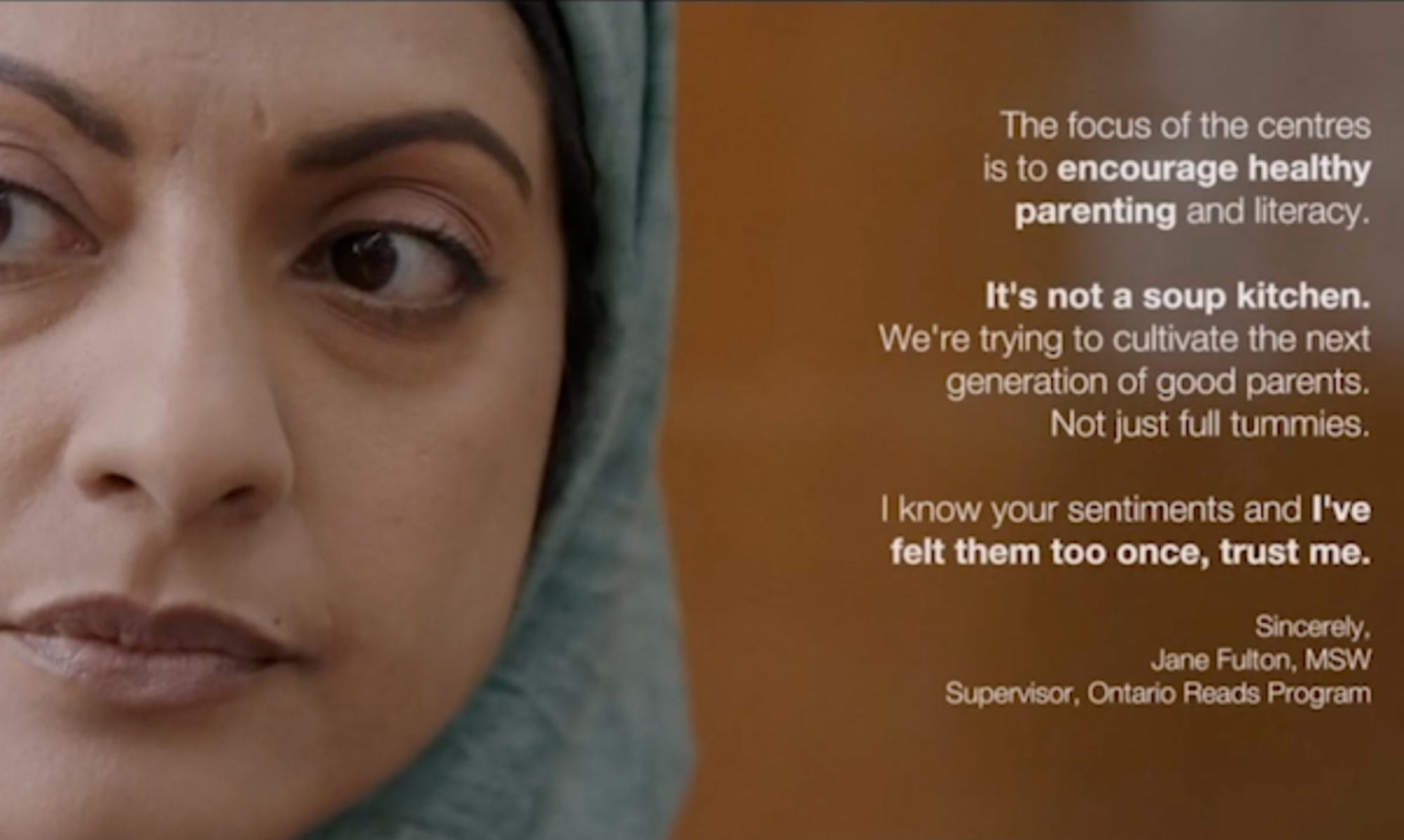

After the creation of a capitalist government system, historical/heritage epics, or movies where history is used as a guideline for plot but is often fictionalized or littered with values important to the ideals of a nation’s government, became extremely popular. Andrzej Wajda, whose work always had a sense of Polish patriotism, even in the 1950s under Soviet rule, followed such a form (Misiak), and Afterimage (2016) is no different. The movie follows Władysław Strzemiński, an abstract artist whose refusal to follow Soviet orders and create socialist realist art leads to censorship, violence, and manipulation. His erasure from his previous status as a reveled artist is only emphasized emotionally with intimate personal scenes humanizing Strzemiński. In contrast, scenes containing Stalinist sympathisers are defined with cold indifference to starvation and death, as well as violent, uncontrolled scenes of chaos.

While the Soviet Union has fallen, it is clear through so many examples like Afterimage in Polish popular culture that there is still a power that modern anti-Russian sentiment holds in creating a modern Polish identity. These trends have only been emphasized in recent years following the success of the Law and Justice Party (PiS).

In 2015, PiS swept Polish parliamentary elections with an outright majority – a feat no party had accomplished in the country since the fall of communism. Founded by brothers Lech and Jarosław Kaczyński, the party creates right-wing policies and holds strong ties to the Catholic Church. They had achieved success in their 14 year existence prior to this election, including winning the 2005 presidency, but their swing to strong conservative and Eurosceptic policies secured their 2015 success. More importantly, however, it revealed an underground movement of radical nationalism slowly breaching mainstream ideas and becoming a significant initiator of civil discourse in the coming years.

The party’s religious ties pretty much require laws to be created that address issues looked down upon within Catholic communities. Anti-LGBTQ+ rhetoric has been openly promoted by President Andrzej Duda and other high-ranking members, leading many to call homosexuality ‘communist’ and having cities be ‘LGBT-Free’ zones. Abortions are illegal, and banning in-vitro fertilization has even come into question. There are also many other controversial policies that are not involved in the religious aspect of the party. Mainly, there are limitations of immigrants from North Africa and the Middle East, with anti-Muslim ideology being heavily emphasized. Additionally, under PiS, Poland has distanced itself from the European Union.

While the laws and policies made by PiS are quite problematic, what is even more disturbing is the party’s censorship of critics versus the promotion of radical supporters. Journalists attempting to judge the party or write opinions about their policies have found themselves facing a plethora of lawsuits and personal threats against the wellbeings of themselves or their loved ones. Opposing politicians have been murdered by Poles fueled with the party’s strong rhetoric (Part 4: Poland’s Culture Wars). Artwork celebrating the LGBTQ+ community has been burnt down right in front of police officers. The promotion of a white, straight, Catholic Pole has overtaken groups in a way that has created a divided nation of hatred.

Poland may not be a communist nation anymore, but even an independent, capitalistic country can be ruled by a party exerting force and oppression to create what they believe is an idealized country. The Law and Justice Party has become the very monster their nation condemns, and no matter how much President Andrzej Duda and other PiS officials distance themselves from their past, they are only creating a repeated history that will doom Poland’s future. Perhaps it is time to bring back Boże, coś Polskę’s original cry: “Return our Homeland to us, Lord!”

Works Cited

- Misiak, Anna. “Don’t Look to the East: National Sentiments in Andrzej Wajda’s Contemporary Film Epics” Journal of Film and Video 65.3 (Fall 2013), pp: 26-38.

- “Part 4: Poland’s Culture Wars.” The Daily from The New York Times, 13 June 2019.

- Trochimczyk, Maja. “Boże Coś Polskę.” Polish Music Center, USC Thornton School of Music.

Media Used

- “Clash of Cultures as Migrants Arrive in Poland.” YouTube, AFP News Agency, 15 Dec. 2015.

- “Poland’s Eurosceptic Law and Justice Party Wins Election.” YouTube, Euronews, 25 Oct. 2015.

- “Poland’s Far-Right Groups March on Independence Anniversary in Warsaw.” YouTube, VOA News, 11 Nov. 2019, .

- “Polish MP: ‘For Me, Multiculturalism Is Not a Value’ | UpFront (Headliner).” YouTube, Al Jazeera English, 9 Nov. 2019.