On June 9, 1848, the Whig National Convention nominated Zachary Taylor as president and Millard Fillmore as vice president. The next day, Boston engineer John E. Gowen wrote to Fillmore. He asked two questions. First, did Fillmore support changing naturalization laws and, in particular, “excluding Foreigners from participating in the elective franchise until they have been here at least Twenty one years”? Second, did the nominee support taxing future immigrants “to such an extent as to protect the American mechanic from Foreign competition in the labor market”? Fillmore responded a week later but refused to answer the questions (Boston Daily Evening Traveller, Sept. 23, 1848).

Immigration was big news in the 1840s. Britons and other Europeans had been arriving on American shores throughout the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries. Slave traders had forcibly brought Africans there until 1808, when Congress banned the international slave trade, and occasionally even thereafter. The discovery of gold in California, just before the United States acquired that province from Mexico in 1848, attracted fortune-seekers from Latin America, Asia, Europe, and Australia. Finally, and most remarked upon in US political debates, many thousands of Catholics immigrated to the largely Protestant United States in the 1840s. They came from the various independent German states and, to avoid starvation amid the potato famine, from Ireland.

Taylor’s and Fillmore’s correspondence includes voices of immigrants and their families. In the volume that we’re publishing this year, for example, you’ll find David M. Nagle. He had led a rebellion in his native Ireland before settling in New York City. On November 3, 1847, he thanked Fillmore for the latter’s “unremitting regard” on behalf of “my adopted fellow citizens.” Three years earlier, Fillmore had heard from Nicholas Carroll, “the son of an Irishman.” Carroll wrote on September 8, 1844, of his family’s support for the US Revolution and of the impact of his Catholic religion on his voting choices.

Writers born in the United States often discussed the politics of immigration. Those politics differed greatly from today’s, partly owing to two legal differences. First, US law did not then distinguish between legal and illegal (or undocumented) immigration. Only in 1875 did Congress begin passing laws that banned certain people’s entry. It excluded Chinese prostitutes in 1875, nearly all Chinese people in 1882, and other specific groups thereafter. In 1924 it passed the first general law limiting immigration from each country. During the United States’ first century, essentially all immigration was legal.

Second, America did not consistently restrict voting to citizens. Many states (and, under federal law, territories), during parts of the nation’s first 150 years, allowed unnaturalized immigrants to vote. Six states did so in the 1840s. The provisions varied but generally extended suffrage to White men who had lived in the state a defined period of time. Only in the 1920s did the last states end the policy. As a result, Americans in most of the nineteenth century did not debate the presence of illegal immigrants, a yet-to-be-created category, but did debate the propriety of noncitizens’ voting.

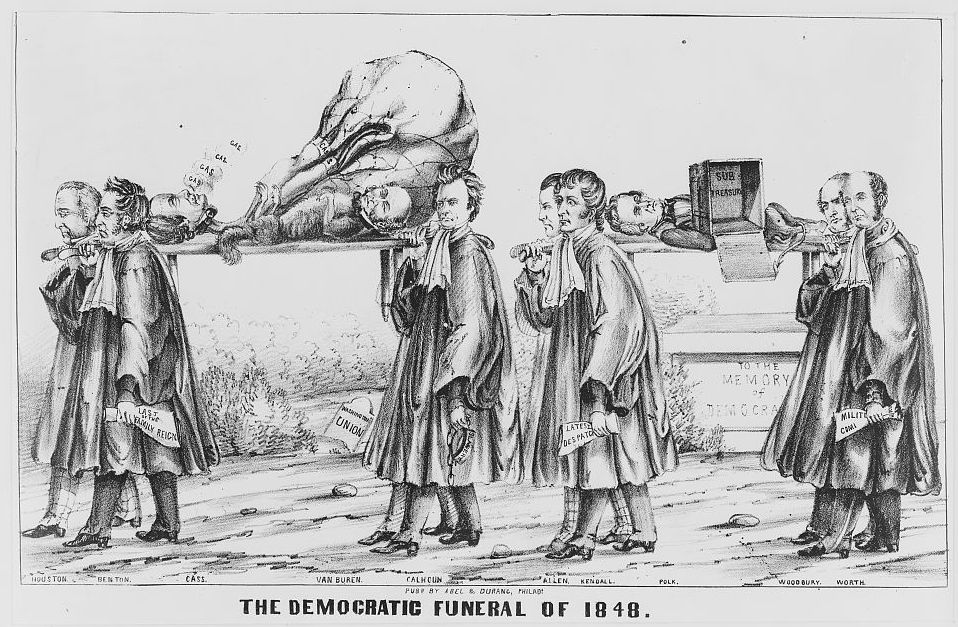

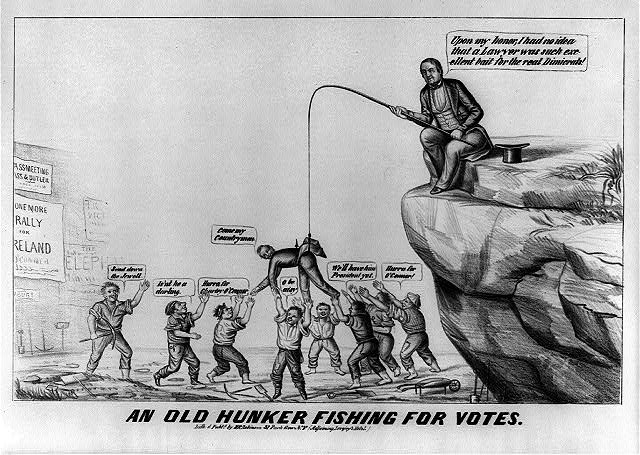

This cartoon of 1848 shows Democratic presidential nominee Lewis Cass “fishing” for Irish immigrant voters. Library of Congress.

Taylor, Fillmore, and the Whig Party both made use of and bristled at immigrants’ votes. They paid particular attention to “Germans”: immigrants from the German states and their US-born and German-speaking children. Because many of those people could vote, Whigs campaigned to them. Chicago’s Samuel Lisle Smith wrote to Fillmore and other Buffalo Whigs on January 17, 1844, to coordinate the development of pro-Whig, German-language newspapers in Illinois and New York. (Smith mentioned “my colleague Mr Lincoln,” a young Illinois politician who participated in the effort and who would become rather famous.) On April 26, Alfred Babcock observed in a letter to Fillmore that New York Whig leaders “have been . . . courting all foreigners and especially the Irish and Catholic forigners.”

Though Whigs sought immigrants’ votes, they weren’t necessarily happy that immigrants—especially recent ones—did vote. John C. Hamilton opined to Fillmore on October 11, 1844, that immigrants should have “immediate access to all social rights” but not “political privileges.” Taylor, the year he ran for the presidency, expressed annoyance at “the immense influx of foreigners into to our Country.” He complained to his son-in-law Robert C. Wood, on February 18, 1848, that they “are carried to the polls & are permitted to vote immediately on their arrival, naturalized or not,” and that “nineteen out of twenty if not more, vote the democratic ticket” (Huntington Library, Zachary Taylor Papers). During the campaign, some accused Taylor of opposing the rights of naturalized citizens. He sharply denied that charge.

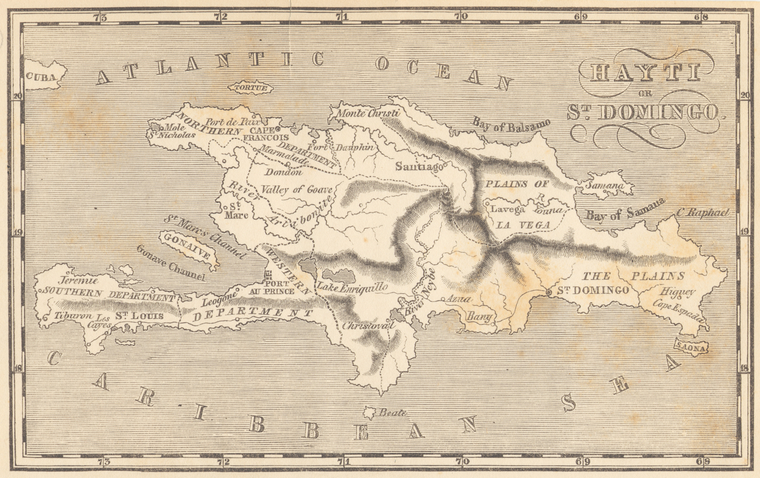

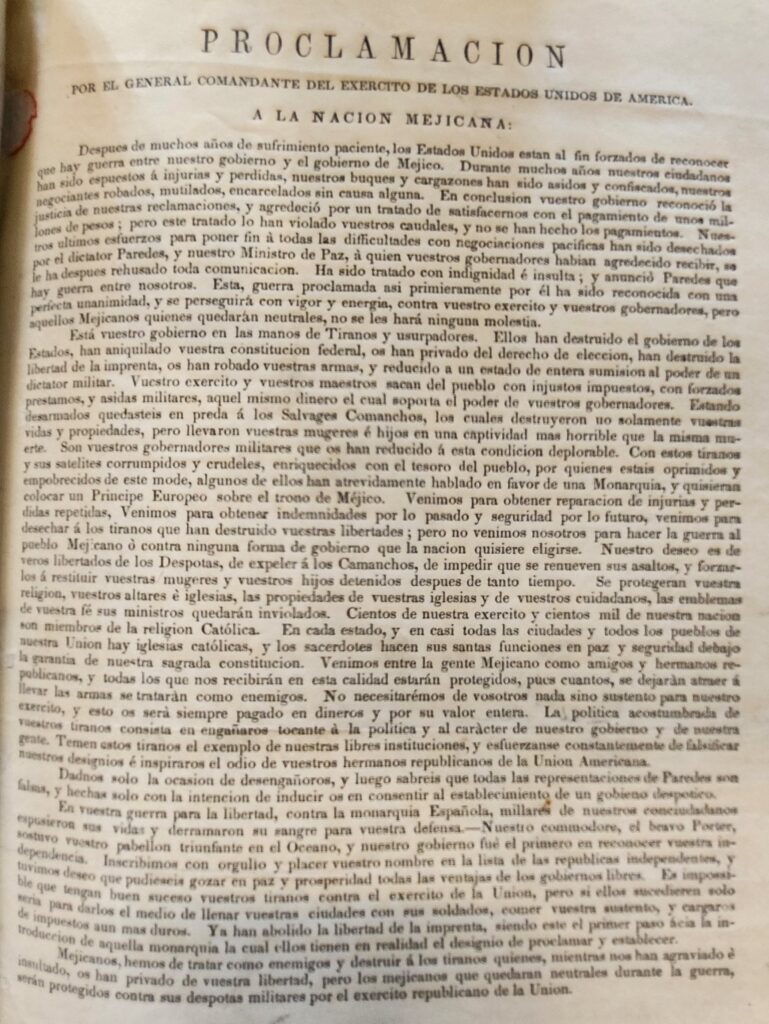

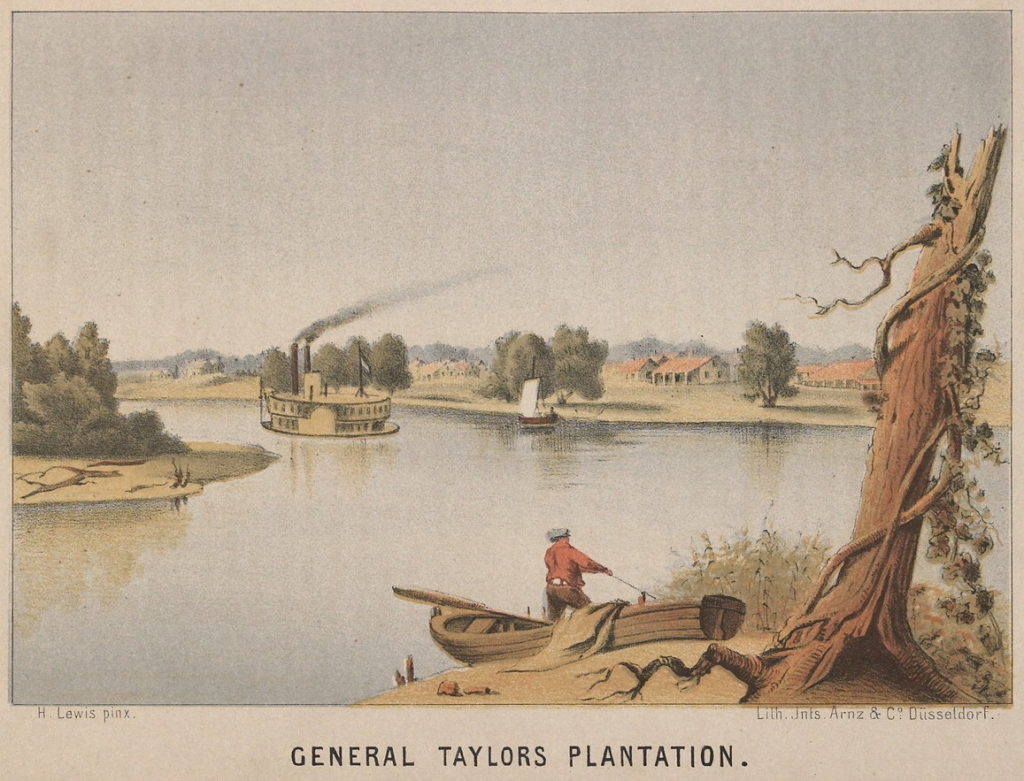

Democrats tended to welcome immigrants from Europe, including Catholics, more wholeheartedly. President James K. Polk was particularly supportive. During the Mexican-American War, he appointed two Jesuit priests to accompany General Taylor’s army. He hoped that they, besides conducting services for Catholic US soldiers, could convince Catholic Mexicans of the United States’ good intentions. When a Presbyterian minister opposed the appointments, Polk labeled him “a hypocrite or a bigotted fanatic.” The Polk administration also argued, during a dispute with the United Kingdom over the status of Irish-born Americans, that US naturalization made one not only a citizen but “a natural born” one.

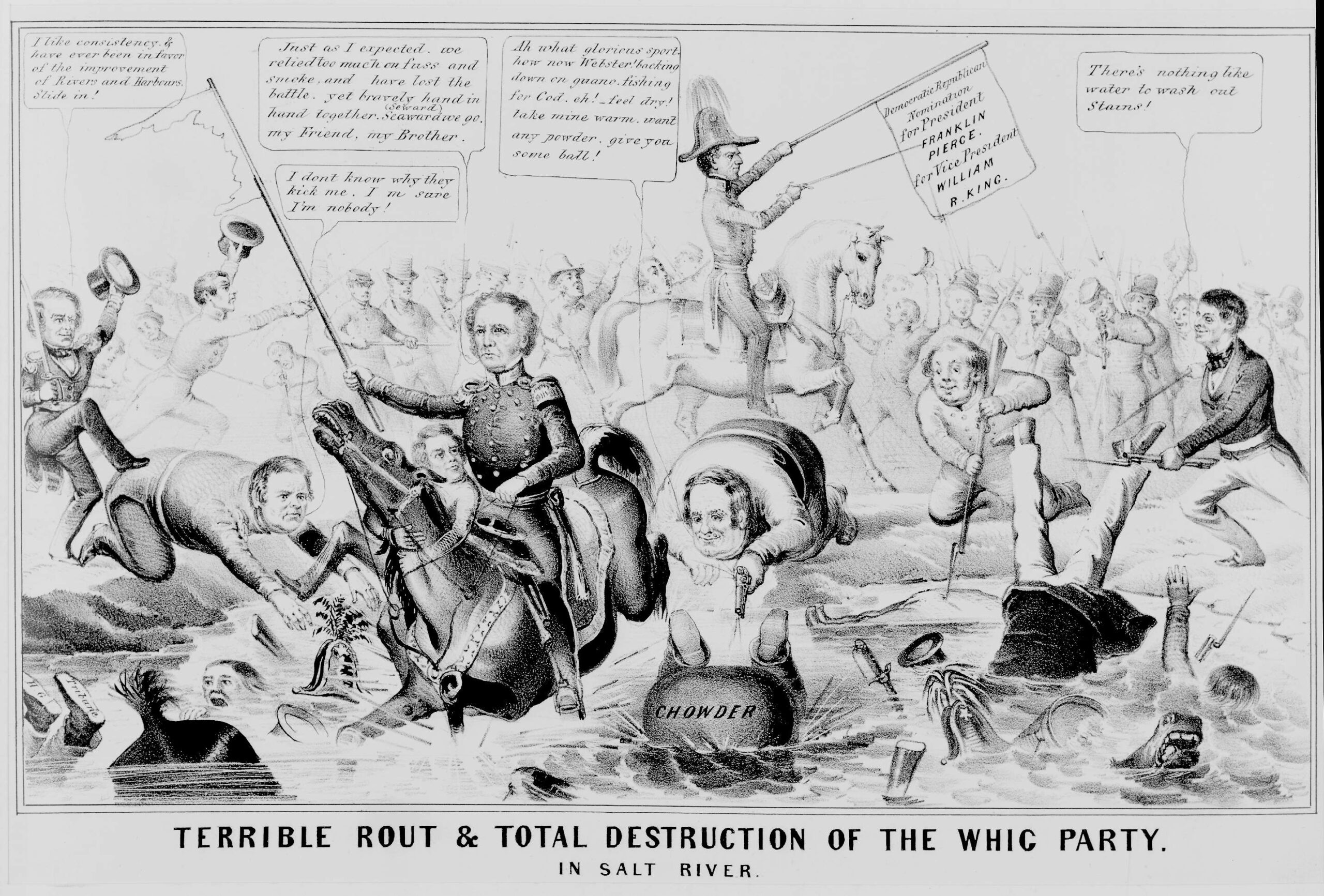

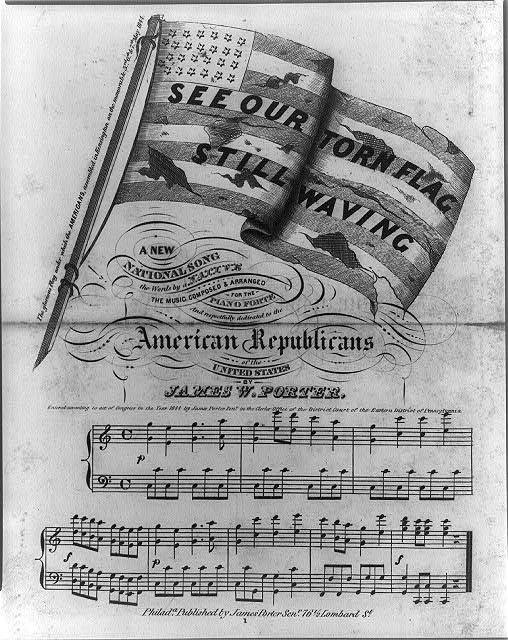

This song of 1844 advertises the nativist American Republican Party. Library of Congress.

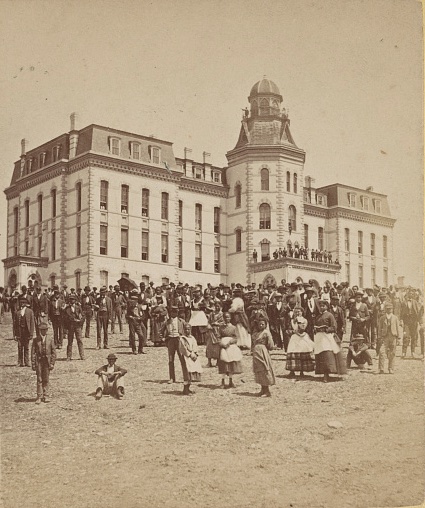

Some politicians, on the other hand, made opposition to immigration and vilification of immigrants centerpieces of their platform. In the late 1830s and early 1840s, committed nativists coalesced into an organization called both the Native American Party and the American Republican Party. (It had nothing to do with either Indigenous people or the as-yet-unestablished Republican Party.) It aimed to reduce immigration and to reduce immigrants’ and Catholics’ political influence. At its convention on September 10, 1847, it recommended Taylor for the presidency (without his having sought the endorsement and long before his nomination by the Whigs). John E. Gowen, who wrote to Fillmore with policy questions in June 1848, did so on that party’s behalf. Its Massachusetts branch wanted to know whether Taylor’s running mate shared its views.

Fillmore’s refusal to answer, given his past efforts to win German immigrants’ votes (and his and Taylor’s general refusals to reveal policy positions), is unsurprising. Later, though, Fillmore moved to the center of nativist politics. In the 1850s, the Native American Party gave way to the American Party, also called the “Know Nothings.” The political arm of the Order of the Star Spangled Banner, a secretive fraternal organization, it promoted the same anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic message. In 1856, the Whig Party having collapsed, ex-president Fillmore accepted that group’s nomination for the presidency. The connection with the secret order was ironic. Fillmore had first entered politics in the 1820s under the Anti-Masonic Party, an organization founded on opposition to secret orders. But his acceptance of the nativist message, one that in the mid-nineteenth century crossed party lines and often had been embraced by Whigs, made pragmatic political sense.