What is experiential learning?

last edit 2024/31/10

Experiential learning is a process whereby individuals learn by engaging directly with experiences and reflecting on their actions. In its simplest form, it is learning through doing, intentionally paired with thoughtful reflection. As David Kolb famously stated in “Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development” (1984), “Learning is the process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience.” This process involves more than just acquiring knowledge—it’s about continually evolving one’s understanding by building on new experiences while adapting or even letting go of prior ideas. As students engage with their environment, both they and the environment evolve, underscoring the adaptability needed across various fields and the distinct learning processes each entails. Graduating students often serve as the primary measure of institutional quality and reputation (Abdel-Meguid, 2024). These graduates enter the workforce, applying their training to enhance their own lives, positively influence others, and contribute to societal progress and the global community.

Community-based learning is the most recognized form of Experiential Learning. It extends the idea of connecting students more deeply to community settings, such as through internships or collaborative projects with local organizations. These experiences promote learning within social contexts, allowing students to learn from more experienced practitioners through observation, interaction, and active participation. This method emphasizes learning within a community of practice where students gradually take on more complex tasks as they gain experience, deepening their understanding of both the subject matter and the social context in which they work. Learn more about the DC Community Impact Scholars program at American University. AU also offers first-year seminar courses that use real-world problems or enduring questions to cultivate intellectual flexibility for future work at the university and beyond. The Complex Problems courses include unique co-curricular experiences, sending you off campus or bringing area experts to the classroom to foster connections among ideas and experiences

Goals of experiential learning

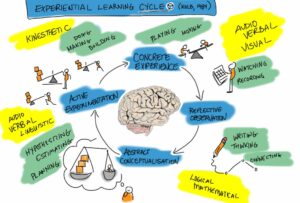

Experiential learning encourages learners to actively engage in four key stages: Concrete Experience, Reflective Observation, Abstract Conceptualization, and Active Experimentation (Kolb, 1984). These stages work together to deepen understanding and application. First, learners participate in hands-on experiences (Concrete Experience), which they then reflect upon to identify patterns and insights (Reflective Observation). From these reflections, learners form broader concepts and theories (Abstract Conceptualization) that they can test and apply in new contexts (Active Experimentation).

“Kolb’s Experiential Learning CYCLE” by Giulia Forsythe is licensed under CC0 1.0

However, Kolb’s model does not explicitly address the social and cultural influences that shape learning. To bridge this gap, it’s essential to integrate these factors into the experiential process by encouraging students to recognize and reflect on their inherent assumptions, biases, and the origins of these beliefs. By doing so, learners become more aware of how cultural contexts influence their perceptions and actions. Omitting how social and cultural factors, such as race, gender, and socioeconomic background, shape these experiences can lead to a teaching approach that assumes all learners engage with experiences in the same way. This ignores how cultural backgrounds and social positions influence how students interpret, process, and apply knowledge.

For example, a student from a marginalized community might experience the same learning event differently than a more privileged peer due to historical and cultural perspectives that shape their worldview. Without addressing these influences, educators may unintentionally reinforce dominant narratives, limiting critical reflection on power structures. The potential impact is a classroom environment where students’ diverse perspectives are underutilized, and the opportunity to foster deeper, more socially conscious learning is missed. By incorporating reflective activities that prompt students to explore how their cultural backgrounds and social contexts shape their learning, educators can create a more equitable and inclusive environment that encourages awareness of broader societal issues.

This approach includes heightened awareness of one’s biases, a better ability to observe holistically and consider qualitative aspects, and the capacity to connect social, environmental, and personal development. Through thoughtful guidance, instructors can help students not only question their assumptions but also draw interdisciplinary connections and form their own conclusions based on a reflective approach to learning.

Application

Instructors make experiential learning available to students by creating environments that foster hands-on engagement and meaningful reflection. First, they design activities that provide real-world experiences where students can directly apply the concepts they are learning. These activities might include simulations, fieldwork, problem-based learning, or other practical exercises encouraging active participation (Concrete Experience).

Take for example, an environmental science course where students learn about water resource management. The instructor designs an experiential learning activity where students visit a local water treatment facility to see how water is processed and managed in DC. During the visit, students observe various processes and interact with professionals in the field, applying the concepts they’ve learned in class about water quality and sustainable resource use.

Additionally, instructors encourage reflective practices by prompting students to think critically about their experiences. This reflection allows students to identify insights, recognize patterns, and confront any assumptions or biases they may have (Reflective Observation). By creating structured opportunities for reflection—through discussions, journals, or guided questions—students can begin to link their experiences to broader concepts.

After the visit, the instructor may ask students to reflect on their experience by asking guided questions: What surprised you about the water treatment process? How does what you observed align with or challenge what we discussed in class? Did any assumptions you held change?

Instructors can then help integrate these concepts by connecting students’ experiences to theoretical frameworks, encouraging them to conceptualize their learning in a broader context (Abstract Conceptualization).

The instructor may facilitate a class discussion that links their observations at the facility to broader environmental policy concepts, such as sustainability, the water-energy nexus, and public health. Students will be then able to deepen their understanding of how these processes fit within larger systems of governance and environmental policy.

Finally, Instructors also facilitate Active Experimentation by motivating students to apply their newly acquired knowledge in different settings, reinforcing learning through continuous practice. By thoughtfully guiding students through this cycle, instructors enable learners to not only absorb information but also apply it meaningfully in both academic and real-world contexts.

The instructor can ask students to create a proposal for improving water management practices in a specific region, applying the knowledge and frameworks they have learned.

How do I integrate experiential learning into my teaching style?

Examples provide by OpenAI (2024), ChatGPT (Version 4.0)

- Design Activities That Encourage Active Participation

- Create hands-on tasks: Incorporate activities that require students to interact with materials, tools, or environments related to the subject. For example, science instructors might use lab experiments, while business teachers could simulate case studies or market analyses.

- Fieldwork and site visits: Arrange field trips or encourage students to engage in their local communities. For instance, environmental science courses could include trips to conservation areas, while political science courses might involve visits to government offices in the area.

- Simulations and role-playing: Use role-playing or simulations to immerse students in real-life scenarios. In a history class, students could reenact historical events, while in law or international relations, they might simulate courtroom or diplomatic negotiations. Take care to collaboratively create guidelines for role-playing or simulations with students before these activities.

- Facilitate Reflection and Critical Thinking

Experiential learning isn’t just about doing—it’s about thinking critically about the experience. Incorporate reflective activities to help students make meaning from their experiences.

- Journals and reflective essays: After hands-on activities, ask students to reflect on what they learned, how it applies to the course material, and what they might do differently in the future.

- Group discussions: Host debriefing sessions where students can discuss their experiences, share perspectives, and connect the experience to theoretical concepts.

- Instructor-guided reflection: Provide prompts or questions to help students think about the social, cultural, and ethical dimensions of their experiences. This aligns with experiential learning’s focus on personal and social development.

- Incorporate Real-World Problems

Present students with real-world challenges that require problem-solving and creativity.

- Problem-based learning (PBL): Project-based or problem-based learning encourages students to tackle real-world challenges by applying course concepts to solve problems or complete projects. These approaches help students develop critical thinking and problem-solving skills while also gaining practical experience. For example, in engineering or public health courses, present a challenge such as designing sustainable infrastructure or solving a health crisis, and guide students through the process of finding viable solutions.

- Community-engaged learning (Service Learning): Service Learning integrates academic study with community service. In service learning, students apply their classroom knowledge to address real-world needs, gaining a deeper understanding of course content while fostering civic responsibility and social justice. The outcome benefits both students and the community, with students emerging as stronger allies, advocates, and even activists. This approach encourages them to contribute positively to their communities while cultivating a sense of social justice. Connect coursework to community issues. Students can apply their learning to projects that benefit local organizations or marginalized communities, like developing a marketing plan for a nonprofit or working on a public health campaign.

- Internships or practicums: For courses with practical components (like education, nursing, or social work), integrate internship or practicum opportunities where students gain professional experience while earning course credit.

- Encourage Collaboration and Team-Based Learning

Experiential learning often involves collaboration, which mirrors real-world professional environments.

- Group projects: Structure assignments so that students work in teams to solve problems, develop solutions, or complete projects. The experience of negotiating roles and working together mimics workplace dynamics and enhances interpersonal skills.

- Peer teaching and feedback: Have students present their findings to their peers and provide feedback to one another. This reinforces learning while fostering collaborative thinking.

- Connect Theory and Practice

A key element of experiential learning is helping students understand how theoretical concepts apply in practice.

- Bridge classroom content with practical application: After introducing a theoretical concept, ask students how it applies to their experience in fieldwork, internships, or projects. For example, in a business course, after learning about market segmentation theory, students could apply the concept by analyzing consumer data from a local company or conducting market research to see how segmentation is used to target specific demographics. This helps students understand how theory informs practical decision-making and strategy in professional environments.

- Use case studies: Present case studies or real-world examples that illustrate how theoretical concepts are applied. Discuss these examples with students, then let them apply the same theories to solve similar problems in new contexts.

- Incorporate Technology and Virtual Tools

- Simulated environments: For disciplines like medicine, engineering, or architecture, virtual simulations (e.g., virtual labs, computer-aided design) allow students to experiment in a controlled, risk-free environment while applying their knowledge.

- Online experiential platforms: Use digital platforms that enable students to collaborate, research, and problem-solve virtually, such as virtual collaborative online international learning projects with students from other universities.

Learn more about how you can make digital research more engaging on our very own online publication!

- Integrate Reflection on Social and Cultural Contexts

Experiential learning can benefit from addressing broader social and cultural factors. The instructor guides students in considering how different experiences are shaped by social, political, and cultural contexts.

- Culturally responsive teaching: Design activities that are inclusive and respect diverse experiences and backgrounds. For example, in a global health course, students could compare public health systems in different countries and reflect on how cultural, economic, and political factors influence health outcomes.

- Critical reflection: Encourage students to reflect on their own social positions and biases as they engage with experiential learning activities. This can help increase awareness of diverse perspectives and promote empathy.

Examples of Scalability

In-person, Small Class:

Partner with a local organization and have students volunteer or work on a project that applies course concepts to a community need (e.g., environmental science students working on a community garden project). Provide logistical support for the community project and ensure that students have time to reflect on their service, connecting their experiences to the course material through discussions or journals.

In-person, Large Class:

Divide the class into teams, with each team working on a different aspect of the service-learning project (e.g., fundraising, outreach, logistics). Rotate responsibilities so that every student has the opportunity to engage in multiple facets of the project. Use large-group check-ins for project updates and organize rotating leadership roles to ensure that the project remains collaborative and scalable.

Online Class:

Arrange for virtual service-learning opportunities where students can contribute remotely (e.g., data analysis for nonprofits, social media management for a community organization). Students can also engage in online advocacy or awareness campaigns that tie into the course content. Use online reflection tools (blogs, discussion boards) for students to share their experiences and learn from one another. Provide regular feedback to ensure that virtual service connects meaningfully to course objectives.

In-person, Large Class:

Divide the class into rotating groups, with each group conducting fieldwork at different times or focusing on different areas of study. Each group then shares their findings with the class.

Use collaborative tools such as shared spreadsheets or class-wide data sets to collect and compare results across the groups. Scale the assignment so that each student participates in part of the fieldwork but learns from the entire class’s collective experience. For more information on how to support and grade group work

In-person and Online (All Class Sizes):

Incorporate regular reflection activities, such as reflective journals, group discussions, or e-portfolios, where students connect their hands-on experiences with the academic material. These reflections can be shared with peers or assessed individually. For large classes, use peer-to-peer reflection where students provide feedback on each other’s experiences, thus reducing the instructor’s grading load. For online courses, use asynchronous discussion forums or platforms like Padlet for students to share reflections and comment on each other’s posts.

Leverage Technology: For large classes or online environments, use tools such as:

- Breakout rooms (Zoom, Microsoft Teams) for small-group discussions or projects

- Collaborative platforms (Google Docs, Miro) to allow teams to work together in real-time

- Polling tools (PollEverywhere, Mentimeter) to gather input from large groups efficiently

For smaller classes exploring art and history, using VR equipment is not only helpful, but a fun tool for students to experience and interact with what they are learning.

In large, small, and online settings, assign specific roles within groups (e.g., leader, recorder, presenter, researcher) to help manage group dynamics and ensure accountability. Rotate these roles throughout the semester to give students diverse experiences.

Examples of Experiential Learning at AU

Dr. Ken Conca and colleagues at American University explored experiential learning through a simulation of negotiations over the Nile basin. In this role-play, students took on roles as international stakeholders, allowing them to engage with complex global issues like environmental diplomacy and water governance. This hands-on approach helps students shift perspectives, understand power dynamics, and explore opportunities for cooperation in international relations. You can read more about the paper here and how it reports that students developed a richer understanding of crisis complexity, emphasizing cooperative opportunities over risk management, evolving their value orientations from environmental to development concerns, and gaining a nuanced view of power dynamics, particularly knowledge-based and institutional power.

Do you have a course you feel incorporates experiential learning? Email your syllabus LearnByDoing@american.edu to be added to the program database.

Learn more about how your school is integrating experiential learning:

Resources

Abdel-Meguid, A. (2024, May 6). Enhancing relevance and amplifying impact: The power of experiential learning in higher education. Higher Education Digest. https://www.highereducationdigest.com/enhancing-relevance-and-amplifying-impact-the-power-of-experiential-learning-in-higher-education/

Kolb, David A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall.

Roccamo, A., & Young, C. (2024, July 24). Unleashing the power of digital research: A game-changer in experiential learning. The CTRL Beat. https://edspace.american.edu/thectrlbeat/2024/07/24/unleashing-the-power-of-digital-research-a-game-changer-in-experiential-learning-ashley-roccamo-claire-young/

https://www.uopeople.edu/blog/what-is-experiential-learning-theory/