Peer Assessments of Teaching Overview

Why engage in peer assessments?

Connecting with fellow instructors to assess one another’s pedagogical approaches can offer critical insights for improving teaching. This process offers instructors the opportunity to get an outside perspective on their own teaching and to learn about other pedagogical approaches. Both instructors are also afforded the opportunity to reflect on their own teaching and integrate new practices. You will notice throughout CTRL Peer Assessment resources that the emphasis is on instructor growth and improvement. The recommendations we provide here are meant to be used within a formative, iterative assessment and feedback practice.

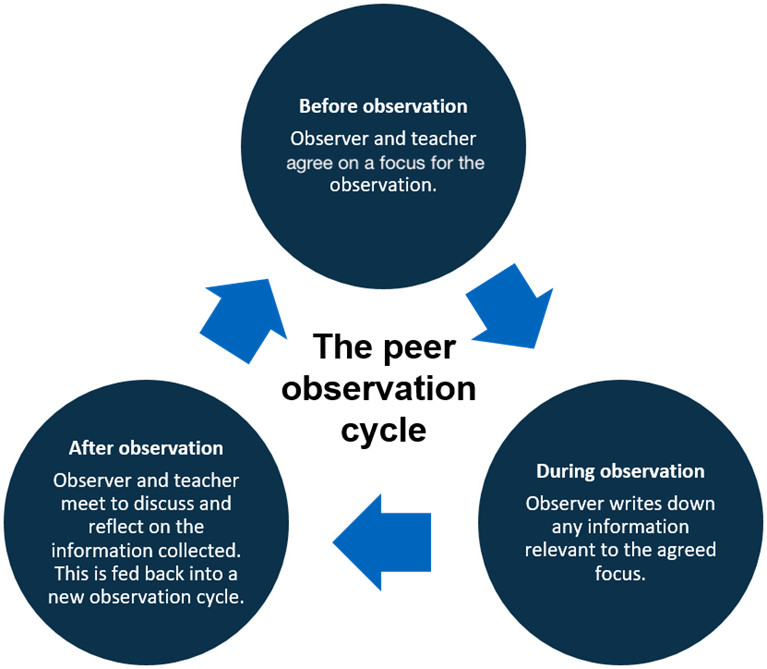

The Peer Observation Cycle. Adapted by Cambridge Assessment International Education from Matt O’Leary’s Classroom Observation (2014).

As illustrated above, the process of peer assessment of teaching is an iterative cycle. This image represents peer observations, but the focus on an ongoing process of improvement is important to all forms of assessment of teaching.

Peer Assessment in Teaching Portfolios

Artifacts from peer assessment, such as peer observations of teaching and feedback on teaching materials, can also be compelling components of a teaching portfolio. The Beyond SETs task force defines peer assessment of teaching as one component of a holistic teaching portfolio; therefore, the peer assessment of teaching should complement other forms of feedback, such as Student Evaluations of Teaching (SETs), and self-assessments in your teaching portfolio. Note, though, that peer assessment materials used for tenure and promotion may be more effectively formatted with other emphases (i.e., emphasizing strengths rather than emphasizing opportunities for growth); contact your school or department for their procedural and formatting expectations if you are planning to use these materials for high-stakes institutional evaluations.

Approaching Peer Assessments

As you begin the peer assessment process, first determine your goals. You will need to share and discuss your goals with your partner before reviewing materials, visiting class, or discussing specific course design changes. Some questions you might consider as you narrow down your goals include:

- What do you want to learn from the process?

- What are your strengths?

- What areas do you have for improvement?

- If you are being observed or sharing your course materials, what type of feedback is most helpful for you?

More specifically, you may think of your goals as questions to which you are seeking answers. Example questions include:

- Are my lessons accessible to students that are new to the discipline?

- Are the learning outcomes clear and appropriate for the course level and sequence?

- Does this course adequately prepare students for subsequent classes in the department/program/major?

- If this is the final class in a series or curriculum, does this class adequately prepare students for their future careers?

- How can I better engage students during class discussions?

- Are my instructional strategies (e.g., lecture, small group discussions, class activities) effective for students learning this material?

Agreeing on these goals with your partner will ease communication and make the process more efficient and effective for both parties.

As you are identifying your goals, decide which materials would best support those goals. Consider: Which aspect(s) of your pedagogical approach do you want to develop? or, Which aspect(s) of your pedagogical approach do you want to showcase in your teaching portfolio? Your peer assessor can provide feedback on many types of pedagogical artifacts. Some options include:

- Course planning and design elements (syllabus, learning management system, course website, etc.)

- Instructional materials (handouts, exercises, readings, lectures, activities)

- Learning assessments tools (tests, ungraded or graded assignments)

- In-class interaction with students, instructor presentations, etc.

Types of Peer Assessment

CTRL has resources to support you in conducting various types of peer assessment. Read through the following pages for detailed information on each practice:

Peer Review of Course Materials

If you are interested in engaging with other forms of peer assessment, we encourage you to reach out to CTRL for support.

Selecting a Peer Assessment Partner

A peer can be any colleague willing to support you! They do not need to be an expert on the content area in which you are teaching; they do not even need to be in your discipline. It might benefit you to work with a peer who is unfamiliar with the content area of the course, as they can offer insight from the perspective of someone who is new to the content, much like a student. Peers from outside of your discipline will likely also be more able to focus their feedback on your instructional strategies and their effectiveness as opposed to the content you are choosing to cover.

When selecting a partner for peer assessment, keep in mind the departmental/unit requirements for your teaching portfolio or other reports on teaching. You should be in conversation with your chair or department head to determine an appropriate peer reviewer if you are utilizing this report for the teaching portfolio. You should consider you and your potential partners’ respective:

- Departments/programs/units

- Status/teaching experience

- Areas of expertise

- Courses taught

- Teaching styles

Keep your goals for the peer assessment process in mind! Consider how these example goals from earlier would guide you in selecting a partner.

- Are my lessons accessible to students that are new to the discipline?

- A peer who is unfamiliar with your discipline would likely be most helpful, as their outside perspective on the content can help you understand how clearly you are explaining concepts. You might ask them to review your syllabus language for how you introduce the course or example assignment descriptions that are designed to spark student interest. Alternatively, you might invite them to observe a class and provide feedback on the way you “hook” students at the start of a lesson.

- Does this class adequately prepare students for subsequent classes in the department/program/major?

- A peer from your unit would likely be most helpful, as they understand how courses in the department, program, or major are scaffolded and can help you understand how your course connects to others, including those they might be teaching. You might ask them to review your syllabus content and trajectory or review an assessment to understand what knowledge and skills students are practicing in the course.

- How can I better engage students during class discussions?

- Rather than choosing an assessor based on the disciplinary home of your peer, you might benefit from working with an instructor whose teaching style you admire, or whom you know integrates many activities and discussions into their courses. You might ask your colleague to visit your class and observe the strategies that you use to engage students. You could also ask them to review the materials you use to guide participation and discussion in class, such as your syllabus, class discussion guidelines, course policies, or grading scheme.

Finally, it is important to select a peer with whom you feel you can have an honest and open discussion of teaching. In addition to interpersonal rapport, consider their rank and other political factors (for example, is there a possibility that you will be serving on their reappointment or tenure committee?) that might undesirably restrict your conversation.

Setting Up an Effective Assessment Process

Every peer assessment should be framed with a pre-assessment conversation and a post-assessment debrief.

- Pre-Assessment Conversation: The instructor receiving feedback should arrive at this meeting with goals for the assessment. They should communicate these goals to the assessor as well as answer any clarifying questions and address any concerns that the assessor may have. This is also a good opportunity to communicate any time frame within which feedback would be most useful and to schedule the debrief conversation.

- Post-Assessment Debrief: The assessor should arrive at this meeting with organized notes, ready to provide specific, actionable, relevant, and timely feedback. Use this time to share what the instructor is already doing well and discuss how they can improve further. The instructor seeking feedback should be prepared to actively engage in this conversation to ensure that the feedback provided stays aligned with their goals and values as an instructor. The assessor should be prepared to take notes so that their documentation of their feedback reflects realistic next steps for the instructor.

Additional information about what to cover in these meetings is included on the pages for each specific type of peer assessment linked above.

Delivering Feedback to Your Partner

Once you have completed your assessment of your peer’s teaching, create a formal document that captures your feedback and debrief conversation in a way that highlights the instructor’s strengths while still focusing on how they can grow and improve their teaching practice. Peer Assessment is often finalized into a one- to two-page formal letter or report that can be used to guide and track ongoing professional development. Incorporate language that suggests paths for growth while avoiding finalistic, punitive language. Consider using your department’s or university’s letterhead.

Here is a suggested outline of a formal feedback letter with some sample language that you can tailor according to your style and context:

- Formal heading

- Introductory paragraph framing your role as an assessor, your peer’s role, and context of the assessment (e.g., type of assessment, brief course description including level and number of students, and any development goals the instructor initially communicated).

- “On [date of pre-meeting], Dr. X and I engaged in a pre-assessment meeting in order to discuss our scheduled observation [or other assessment]. During this time, we discussed x, y, and z.”

- Paragraph or bullets describing what the instructor is doing well.

- “The aspects of Dr. X’s teaching that support student learning include…”

- “The following elements of Dr. X’s course design effectively apply evidence-based best practices for supporting student learning:”

- “Pedagogical strengths:”

- Paragraph or bullets describing what the instructor might try doing differently to improve students’ learning. Limit this section to one to three items most relevant to the instructor’s goals, since more than this can feel overwhelming to the instructor. (Additional areas of improvement may be addressed in future iterations of the peer assessment process.)

- “We also discussed some elements of Dr. X’s teaching that Dr. X will continue to develop. The first area is…. To address this, Dr. X will try….”

- “Listed below are the aspects of Dr. X’s teaching that might be improved to better support student learning, along with some steps Dr. X will take to make those improvements.”

- “Growth areas and next steps:”

- Closing remarks briefly summarizing strengths and areas for improvement as well as describing next steps that the instructor might take to further develop their teaching practice.

This letter may be accompanied by less formal documentation, such as notes, a rubric, or annotations, according to the type of assessment provided.