I’ve been thinking a lot about AI.

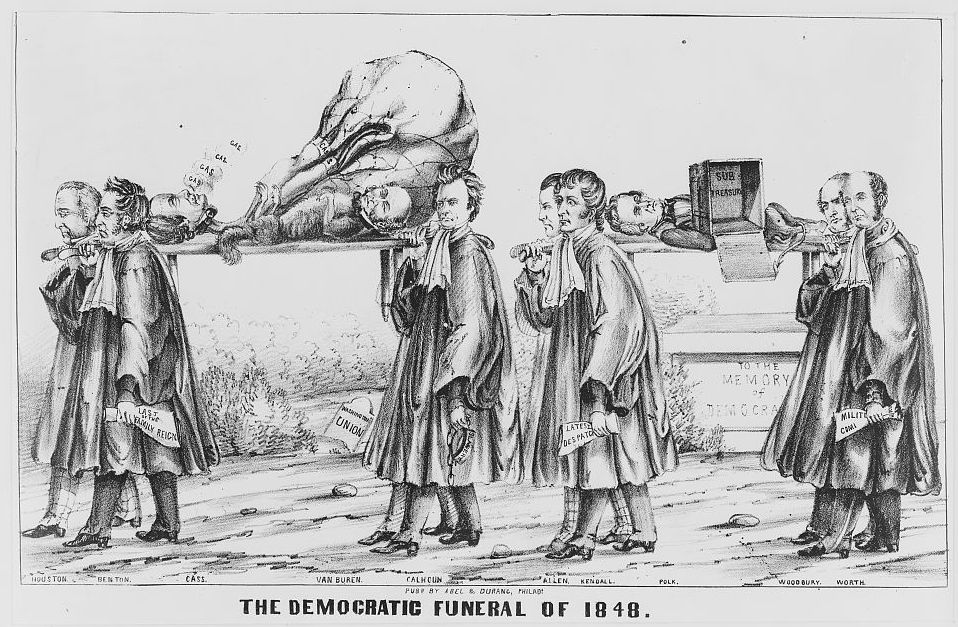

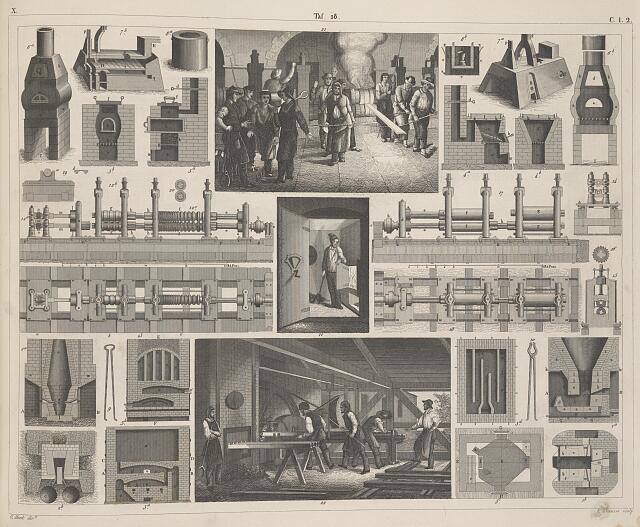

The notion, in its broadest sense, is not new. The mid-nineteenth century, as I have written elsewhere, was a period of rapid scientific innovation. That innovation extended to what some described as artificial intelligence. On September 29, 1853, the New-York Tribune reported on a wondrous shop in which “intelligent machines were doing the work, once done by thinking and toiling men.” One chopped iron bars, one cut steel plates, and one bore holes into wooden wheels. The journalist believed that a central machine, not the “few men made of flesh,” was running the operation. Only months after Millard Fillmore’s presidency, newspapers from Vermont to Indiana reprinted the account.

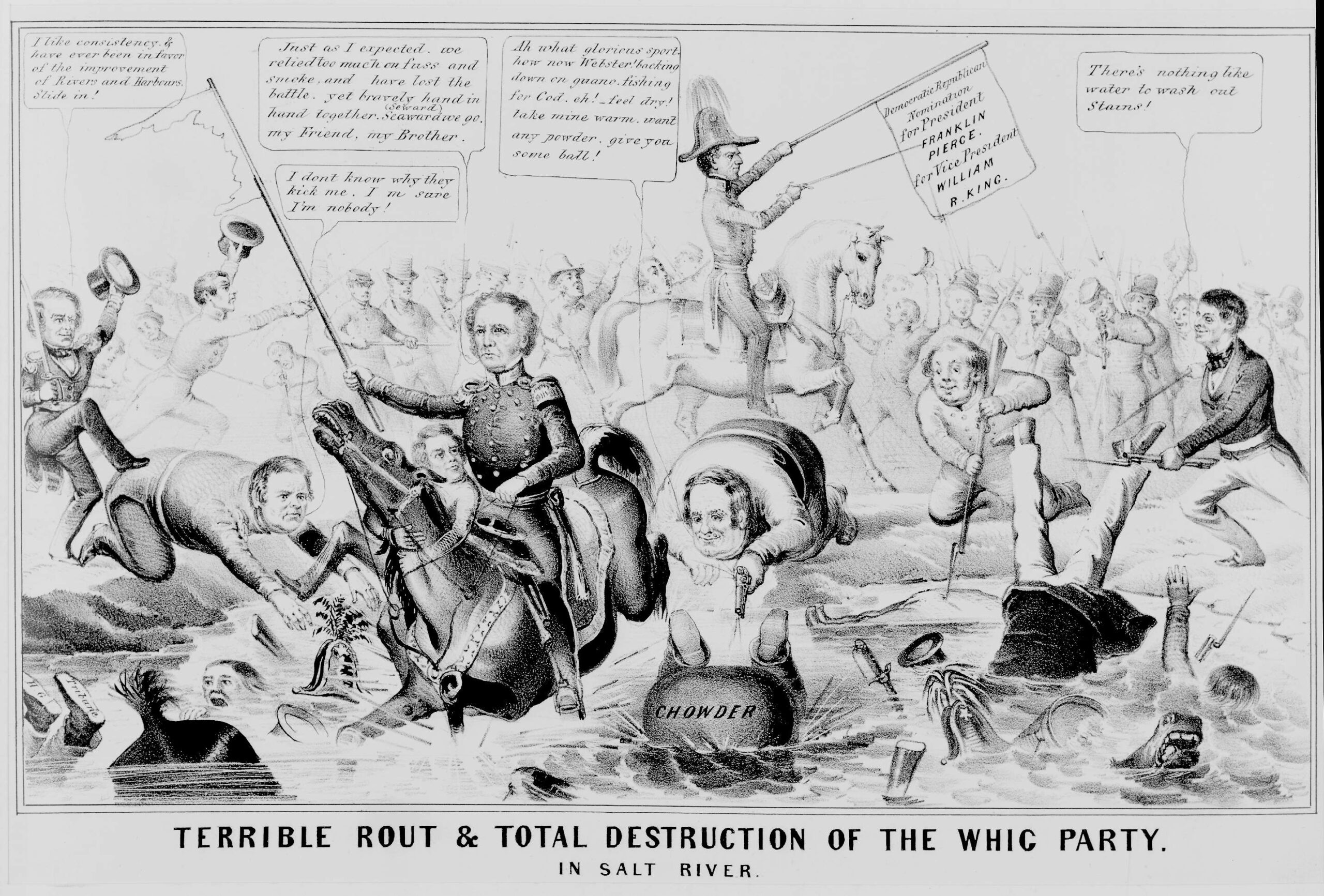

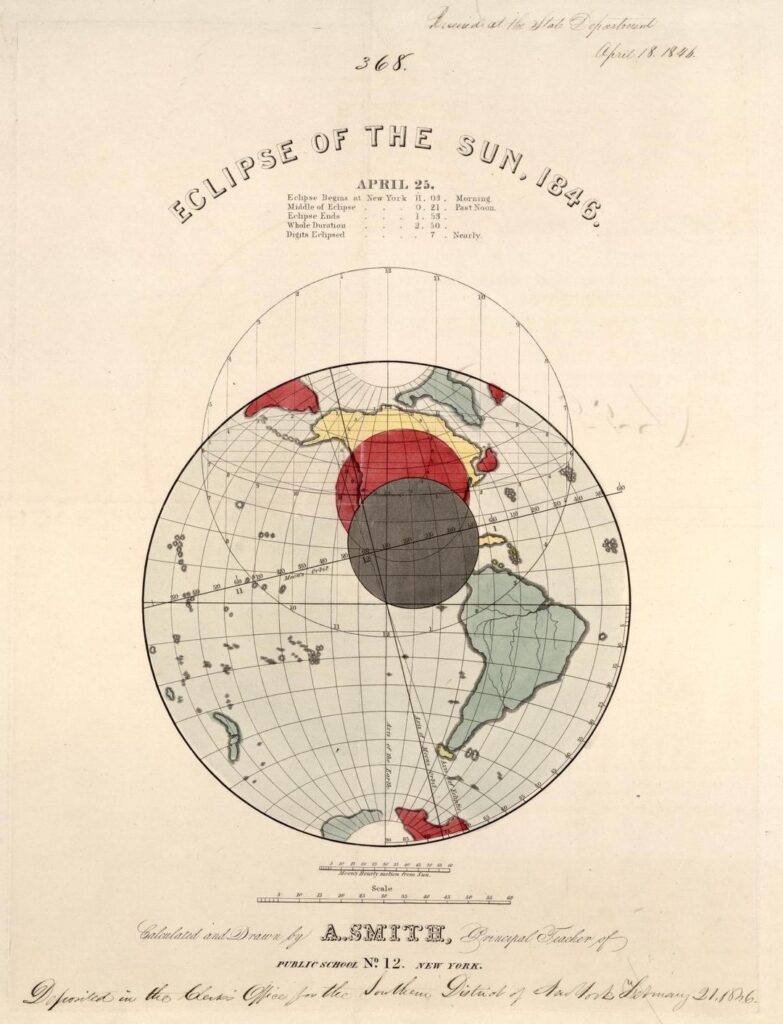

Over the next hundred seventy years, other technologies arose that some likened to the mind. In 1888, a few observers dubbed Thomas Edison’s phonograph an “intelligent machine.” Like a human, after all, it could preserve and reproduce speech. Cameras, soon thereafter, began to remember moving images. In the 1950s, computers could store and analyze massive amounts of data, and scientists and journalists started referring to “artificial intelligence.” Computers moved into people’s homes in the 1970s, the public internet emerged in the 1990s, and social media and smartphones appeared in the 2000s. OpenAI’s ChatGPT burst onto the scene in 2022, exposing many to recent developments in “generative”—and, on the screen, humanlike—AI. Many competitors soon joined that product. People use them today for everything from composing emails to, for some reason, animating antebellum presidents.

But I am not here to tell the history of modern technology or of AI. You can turn to better qualified historians, such as Sarah Igo, Rebecca Slayton, and Aaron Mendon-Plasek, for that. They gave a briefing on the subject for Congress and the American Historical Association.

I am here to discuss the impact of AI, in 2026, on the editing of historical documents. What role can and should it play?

Metalworking machines, depicted in Iconographic Encyclopaedia of Science, Literature, and Art, by Johann G. Heck (New York, 1851), vol. 2, div. 10, taf. 28. Library of Congress.

In this blog, I often have listed and occasionally have detailed the stages of documentary editing. To make writings of historical actors accessible to today’s readers, we editors (1) locate manuscript documents within our project’s scope, (2) select those most useful to readers, (3) transcribe them, (4) proofread the transcriptions, (5) translate documents not originally in English, (6) write annotations identifying people and topics, (7) list the locations and subjects of documents we do not publish, (8) write introductory matter and indexes that help readers navigate the collection, and (9) publish the edition. Technological and cultural developments have prompted adaptations and improvements in each of these stages. Locating documents, for example, used to mean visiting libraries and archives; later, it also included scrolling through microfilm reels; now, it also includes searching online image databases. Indexing used to mean laying out stacks of index cards; now, thank goodness, software facilitates the process. Publication used to mean printing books; now, in addition, it means producing searchable websites. I could go on, but you get the idea.

In short, the way we do each stage evolved, but we (professional, human editors) continued to do each stage. We still began with manuscript documents and gave our readers clearly typed, easy-to-read transcriptions and notes.

Until, perhaps, last November.

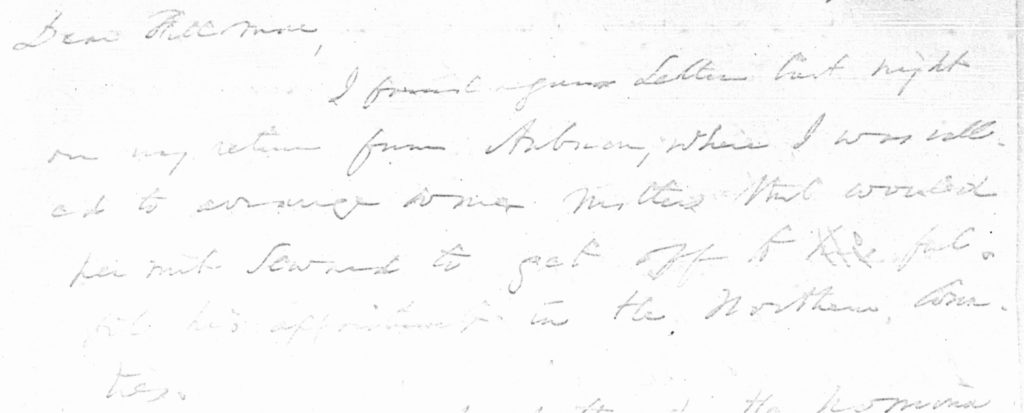

Transcription always has been one of the most challenging and most important elements of documentary editing. Professional editors decipher bad handwriting (in antiquated cursive, with faded ink, on damaged paper), turning it into easily read type, so that our readers don’t have to. I described the process, years ago, in “Transcription 101.” I might have added that reading old cursive was about as challenging for computers as it was for humans. Optical character recognition (OCR) software has, for decades, been able to read printed type fairly well. That’s why you can search for a keyword in a pdf document or an ebook.

But technology, even with recent developments in AI, struggled with cursive. Last year, a pair of historians tested the handwriting recognition abilities of Google’s Gemini (2.5 Pro) and Anthropic’s Claude Opus (3.7), two of the most successful large language models (LLMs)—general AI systems that try to answer all kinds of questions. They asked the LLMs to read English-language cursive from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Gemini got 11 percent of words wrong and 4 percent significantly wrong; Claude missed 16 percent and 10 percent significantly. Meanwhile, a project called Transkribus, developed by a cooperative of academics specifically for handwriting recognition, got about 20 percent of English words wrong but less than 10 percent wrong once trained on a specific document collection. Two historians transcribing a plantation tourist register from the 1930s, in an analysis published last week, found a customized version of OpenAI’s GPT-4o, released in 2024, to misread 12 percent of dates, 27 percent of names, and 36 percent of locations.

These tools are impressive and helpful. If you have a handwritten document and lack the time or training to transcribe it yourself, they can tell you the basic content. Historians, genealogists, students, and anyone whose forebears left behind letters can make great use of them. But editors, I have found in conversations, are divided over their value for producing authoritative editions. Ensuring accuracy for generations of readers, few of whom will ever look at the manuscripts, requires extensive proofreading and correction of the AI-generated drafts. Some projects have still found those worthwhile as a start. Others, including the Taylor-Fillmore project, have continued employing humans—historians and students—to transcribe. Even some giant transcription undertakings, which might reasonably see AI as a timesaver, have kept relying on people. The National Archives, aiming to ease public access to official records in US history, declared that “reading cursive is a superpower.” By early 2025 it had recruited thousands of volunteers to type up documents stretching from the colonial era to the twentieth century.

Then came Gemini 3 Pro.

Google’s latest version, released on November 18, 2025, changed things. I can’t tell you how it works. I’m no computer scientist, and even a historical colleague with far superior technological expertise is uncertain about what Gemini is (for lack of a better word) thinking. But I can report, from others’ testing and mine, on the quality of its handwriting recognition. It’s good. Really good. Other blogs’ headlines make that point dramatically: “Gemini 3 Solves Handwriting Recognition and it’s a Bitter Lesson”; “The Writing Is on the Wall for Handwriting Recognition”; “When the Machine Finally Learned to Read: Gemini 3 and the Question of ‘Good Enough.’” The first of those, by the AI-expert historian I just mentioned, announces that his team’s test of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century English-language documents (the same ones tested earlier with Gemini and Claude) revealed great progress. Gemini 2.5 Pro’s 11 percent word errors and 4 percent significant errors were down in Gemini 3 Pro to 4 percent and 1 percent. The second blog piece reveals Gemini 3’s “perfect” transcription of George Boole’s (bad) handwriting from 1850. The quality left that historian “stunned.”

Google offers a free preview in the Google AI Studio. The unpaid version has several limitations, including on usage (it will only transcribe so many pages per time period), customization, and privacy. But it allowed me to test the model with letters from our corpus.

Gemini’s results with the Taylor and Fillmore letters are similar to those with blogging colleagues’ documents. I first gave it a letter chosen essentially at random—one that we had accessioned early and that was at the top of our list. It did a great job. But the handwriting in that letter was pretty good. So I turned to my old friend Thurlow Weed, the Whig Party boss whom I’d sampled for my “Transcription 101” entry because of his horrendous cursive. To my awe, the virtual mind successfully read nearly every word of Weed’s hastily scribbled page. I’ve subsequently tried other hands, with similar results.

Gemini doesn’t get everything right. In one letter, it misread “Vetos” as “Votes,” an error that drastically changed the meaning of a sentence about presidential rejections of congressional bills. It has a lot of trouble interpreting nineteenth-century punctuation and capitalization. It only occasionally recognizes superscript, and it doesn’t even try (unless I’m overlooking a hidden feature) to preserve underlines. It gives up quickly on truly horrible images such as this. But, let’s be honest, human readers will often have those same problems. I haven’t quantified the results, but Gemini gets the large majority of words right in documents of reasonable quality. When I tested it (as you can) against several other LLMs that colleagues had commended for handwriting recognition and ethical issues, I found Gemini far more consistently accurate. The latest version of Claude, dubbed Opus 4.5, has received good appraisals, but its paywall has delayed my testing it.

What does this advance mean for documentary editing? Last July, Microsoft concluded that historians’ skills are among those most likely soon to be replicated by AI. Last month, a historian-blogger responded, as others have, by asking outright, “Will AI Replace Historians?” She answered no. (Phew!) The concern mirrors those expressed throughout the history of AI. The journalist in 1853 described the machines as “doing the work, once done by . . . men.” A defender of the phonograph admitted that “stenography will not be needed so much” but assured critics that “an intelligent machine is not going to hurt intelligent laborers or employees.” Also in 1888, though, a writer for the Woman’s Tribune lamented that “the steam engine and the well-nigh intelligent machine of man’s invention, put man farther and farther away from the assurance of employment.”

I appreciate the trepidation and the shock value attached to existential questions. No one wants their “superpower” to become irrelevant. But let’s look at this more systematically than fearfully. Instead of asking whether AI will replace documentary editors, I pose a practical question that should become a central one for our field: To best accomplish the goals of documentary editing in the twenty-first century, in what ways can and should editors incorporate AI into our process? With attention to pragmatism and ethics, I offer a few initial proposals.

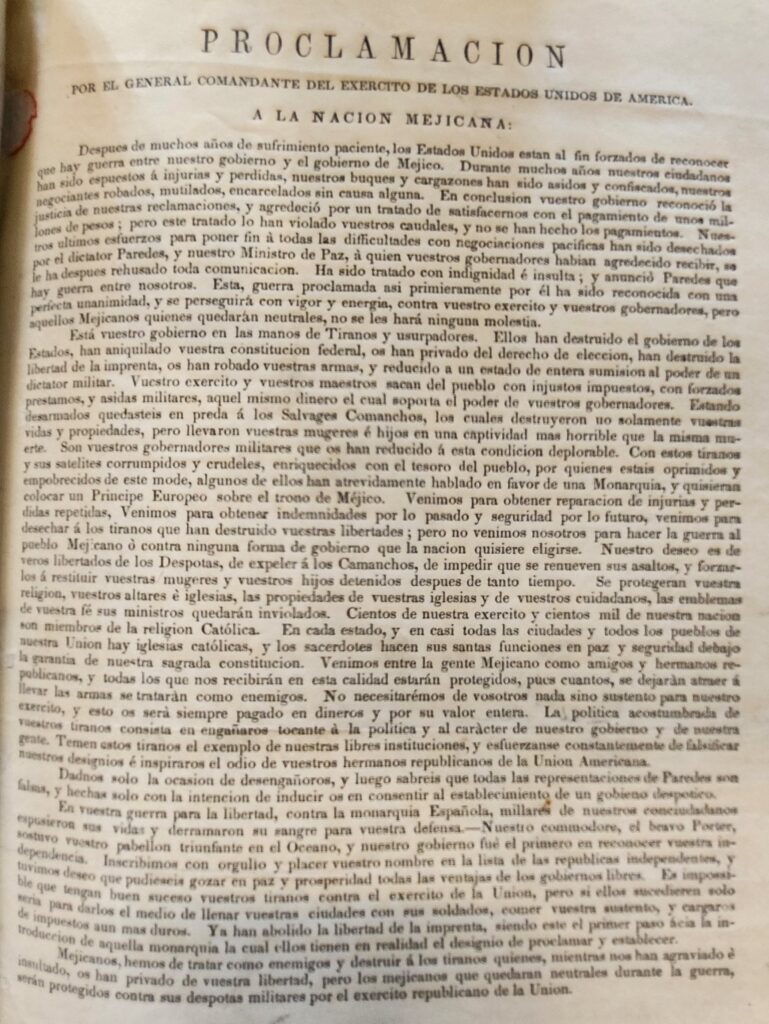

First, let’s return to the editing tasks besides transcription and proofreading. Most seem, to this editor, ill-disposed to robotic labor. Locating documents? Perhaps someone will develop an AI-powered drone that can fly into archives and leaf through folders of manuscripts, or an AI system that can scroll through microfilm reels and reliably identify which frames contain letters to Taylor and Fillmore (who aren’t always named). Until then, the canvass must depend on human eyes, hands, and brains. Selecting those worth publishing? That means curating a selected edition for use in classrooms, libraries, scholarly research, and historical exploration. Anything requiring judgment, particularly about what humans need and want, must be done by humans. Translating into English? Certainly Google Translate and AI-based tools can provide quick readings for research purposes. But, as a professional translator has explained, reliance on such tools for publications sacrifices the nuanced linguistic understanding of (and employment opportunities for) people immersed in the meanings of words in a particular time and place.

Researching and writing annotations? Just as we editors have never left our readers on their own to trust Wikipedia or whatever shows up first in a web search, we will not abandon them to the response of a chat box. When they read a letter by Thurlow Weed or about a particular presidential veto, we will furnish a short biography or explanation that they can rest assured was written by expert scholars after research in reliable primary and secondary sources. Listing the letters not published? As with annotations in notes, these very brief topic summaries are best written by historians who understand the letters’ context and can judge the keywords most meaningful to fellow readers. Besides, factchecking the results would take just as long as composing them. Writing introductions and indexes? Surely AI could produce such things, but I believe that human editors know best how to encapsulate the stories in their own edition and how to guide readers through it. Publishing? We defer to our wonderful colleagues at the University of Tennessee Press and the University of Virginia Press’s Rotunda imprint on whether AI can aid their work, but we certainly will never replace them. Overall, AI systems may indeed assist us editors steps such as searching documents while we canvass, annotate, and index. But we must continue to do the ultimate work ourselves if readers are to trust and benefit from our product.

That brings us back to transcription and, closely tied to it, proofreading. To assess the value of AI, we must remind ourselves of documentary editing’s goal. Our profession aims to produce reliable, even authoritative, versions of historical texts. We provide access to the words of historical actors in editions that readers will rely on for a century or more. Accuracy, therefore, is paramount. We ensure that every word, every letter, every punctuation mark, and every formatting element appears as its author wrote it. (If we must make changes, for ease of reading or due to the limits of printed type, we explain those in the front matter.) Some AIs, especially Gemini, produce very nearly accurate transcriptions as far as the words go. For many uses, those transcriptions are good enough. But, for a documentary edition, “good enough” is not good enough. Nowadays, we might even define our goal, in transcription, as to produce something better than AI: a more accurate, more dependable, more professional version of the text than readers can get at home either by straining their eyes or by asking a chat box. We produce authoritative texts that can be used to answer questions about the past by readers and, for that matter, by AI itself.

Furthermore, in some respects, the best LLMs still fall short of “good enough.” As I noted, even the impressive Gemini Pro 3 occasionally misses a key word (“Vetos” vs. “Votes”), has difficulty distinguishing authors’ nonstandard capitalization, and often misreads punctuation (conflating, for example, hyphens and em-dashes). It doesn’t reproduce some formatting elements, and it seems reluctant to admit—and identify, as we do in our edition—uncertainty about words. It’s inconsistent in whether it follows my instruction to ignore authors’ line breaks, sometimes insisting on (digitally) hitting “return” at the end of each line of text.

I discovered another shortcoming when I asked Gemini a question about overwritten text. If an author wrote one word, then covered it up with another, our project policy is to transcribe both. We thus give readers information about the author’s writing (and thought) process. Our transcription looks like this: “original text ^revised text^.” When I was struggling to decipher a covered-up word, I imagined that Gemini might be able to figure it out. Not only did it fail, but the author’s correction process hindered its ability to read even the final text. Gemini argued with me about my (correct!) reading and my (correct!) assessment that the author had overwritten a word. AI is not replacing the transcriber and the proofreader any time soon.

But AI can help. Let’s consider our traditional procedure. Once we Taylor-Fillmore editors have located, imaged, and accessioned a letter and selected it for publication, we assign it to a transcriber. That may be a student intern or one of us two editors. That person types a transcription from the original, then proofreads the transcription against the original. Then one of the editors (not the transcriber) proofreads it again. Then the other editor proofreads it yet again. Finally, the editor/director (yours truly) reviews any remaining uncertainties or disagreements and finalizes the transcription. If necessary, one of us travels to the archive to check the original manuscript for words that were unclear in the scan or copy from which we transcribed. Altogether, toward producing the final transcription, the manuscript is scrutinized at least four times by at least two people, including both of our trained and experienced editors.

Where can AI fit in? Its best place, if any, seems to be at the very beginning. Gemini, or whatever model is best next week, usually produces a very passable first draft. We can use it for that but not expect of it anything more. The initial transcriber, especially for a long letter, may save time and eyestrain by running the manuscript images through this new technology. They must then add and adjust formatting to compensate for Gemini’s limitations and prepare the document for our systems.

Every proofreading stage, however, must still follow. We never relied on one person’s reading of a manuscript, even if that person was a PhD-educated professional with many years of experience. So we would not rely on one AI’s. Only with all the usual proofreadings, by the transcriber and by both editors, can we promise to catch errors and guarantee a reliable text. Only then, as professional editors, can we take proper responsibility for our work. Furthermore, we are not willing to sacrifice human employment and educational opportunities for the speed associated with AI transcription. As university-based scholars, we design internships to benefit the students as much as the project. We must continue to help students learn about antebellum America, documentary editing (including reading cursive), and methodological debates such as the roles of AI. In short, we can best use AI to improve quality, not quantity. It shouldn’t speed up the process, because each human must still carefully examine each document, but it can become one more pair of (digital) eyes that do so.

In sum, returning to the “will AI replace us?” question, the answer is no. An AI can produce a good but imperfect transcription from a digital image, but it cannot locate and image documents, judge which of them readers should see, produce authoritative transcriptions, and supply reliable annotations and indexes. A chat box’s transcription does not a documentary edition make. But the “how can we use AI?” question has real answers that benefit editors and ultimately readers.

Editors, evaluating their own projects and discussing innovations with colleagues, should continue to identify the best ways to use AI. I am writing this blog entry, in part, to open that conversation. We should, though, be wary of changing our process too often. I read of other industries’ reshaping their workflows (and shrinking their workforces) multiple times each year amid rapid AI advances. For businesses working on short timelines and beginning new projects every few months, that may make sense. For editors spending many years on a single project, it does not. There’s a reason why I worked on a project still using WordPerfect for DOS and 3.5-inch disks in 2009 and on one still using card catalogs in 2019. The editors weren’t ignorant or fearful of technological change. Rather, they knew that migrating materials to new systems would take time and effort that was better spent editing the documents. The migration from one technology to another, furthermore, risks producing inconsistent results. If volume 2 differs in structure or appearance from volume 1—say, its index organizes topics differently—readers may have difficulty navigating them together. Some midstream innovations are necessary, but redesigning workflows every time a new gadget or a better LLM comes out is neither efficient nor responsible.

Beyond documentary editors, the question of how to use (or resist) AI has prompted discussion among historians, other humanists, and academics generally. The University of Virginia Library, last month, released the practically and ethically driven UVA Archival AI Protocol. American University hosted the Artificial Intelligence Research Conference in February and, here at the School of Public Affairs, convenes the SPA AI Teaching Practices series each fortnight. The National Council on Public History has been hosting a wonderful speaker series on Ethics, AI, and the Public Humanities. Those who produce and those who use documentary editions have an important part to play in crafting those conversations and applying their lessons to our work.