Accessible Course Design: Universal Design for Learning

last edit 2023/6/3

Introduction

Universal Design (UD) was inspired by architectural design techniques for accessibility pioneered by Ronald Mace at North Carolina State University. In architecture, UD calls for “the design of products and environments to be usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialized design.” (Ronald Mace, Center for Universal Design, 2008). One common example of universal design is the curb cut, where a sidewalk is “cut” with a ramp to allow for easier access to the street. The curb cut was originally developed for those who use wheelchairs and/or have mobility needs, however this cut curb also helps bikers and people pushing strollers or grocery carts, as well as other pedestrians.

In education, Universal Design for Learning (UDL) was first introduced by Ann Meyer and David Rose when they founded the Center for Applied Special Technology (CAST). UDL calls for designing a curriculum from the beginning to accommodate all kinds of learners, especially those with disabilities. A UDL curriculum takes into account the rich and varied experiences and circumstances students bring to the classroom and proactively puts in place plans for all students to succeed.

Remember, there is no “average” student and designing learning activities or assessments for a purported “average” group of students leaves many students on the periphery. Students left out typically include our disabled students, but we might also see that other students such as those of non-dominant cultural or socioeconomic backgrounds or English language learners, are not taken into consideration. A UDL approach plans for these variances so that instructors intentionally remove potential barriers to students outside the average and increase learning access to the widest variety of learners.

Importantly, under a UDL framework, the learning goals for students do not change. Instead, UDL promotes flexibility and adaptation of the classroom environment such that all learners can succeed and achieve the course learning goals. UDL proactively promotes the inclusion of multiple ways for all students to demonstrate mastery of the course learning goals, instead of retroactively providing accommodations or alternate assessments. For example, a UDL-aligned assessment could allow students the opportunity to share the results of a research project as a live presentation, a pre-recorded presentation, an essay, or even a series of social media posts.

The Principles

There are seven key principles to Universal Design:

- Equitable: Does the learning experience provide the same means of access for all students?

- Flexible: Can the learning experience accommodate a range of individual preferences and abilities?

- Simple and Intuitive: Is the learning experience easy to engage with regardless of prior experience, language skill, or level of concentration?

- Perceptible: Does the learning experience provide multiple (& redundant) modes of communication?

- Error-tolerant: Does the learning experience minimize the hazards/consequences of student error or mistakes?

- Low Physical Effort: Can the learning experience/classroom minimize physical fatigue and cognitive overload? Does it promote ease of use and comfort?

- Size and Space for Approach and Use: Is there appropriate size and space provided in the learning environment for approach, reach, manipulation, and use regardless of user’s body size, posture, or mobility?

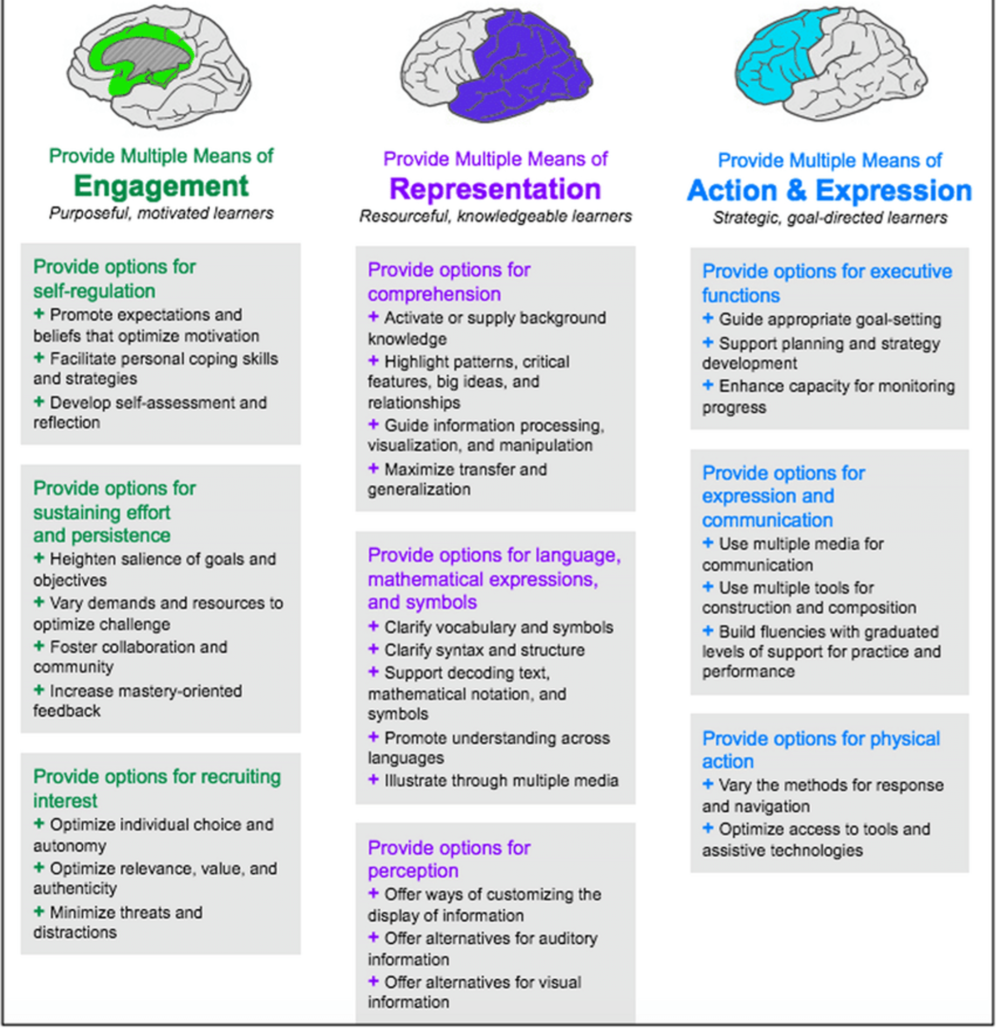

In addition, CAST developed 3 related principles of Universal Design specific to learning:

- Multiple means of engagement (the “why” of learning): Tap into learners’ interests, challenge them appropriately, and motivate them to learn

- Multiple means of representation (the “how” of learning): Give learners various ways of acquiring information and knowledge

- Multiple means of expression (the “what” of learning): Provide learners alternatives for demonstrating what they know

Why use UDL?

- It promotes equity and an inclusive learning environment

- It is beneficial to all students regardless of ability, age, race, class, gender, and/or prior knowledge

- It allows instructors to value and plan for diversity within their classrooms

- It is beneficial to instructors because varying student needs are already considered and planned for, which reduces logistical and structural barriers students encounter and need assistance navigating, saving instructors time

- It allows a course to accommodate a wider variety of student needs and may eliminate learning barriers, so why not?

UDL Strategies

Start Small! Focus on a specific course challenge, session, or assignment.

Integrating every aspect of UDL with every aspect of a course is a daunting task! Starting small by applying UDL to one assignment or lesson can help you become familiar with the framework, learn what works and what does not within your own teaching context, and better prepare you to integrate UDL into all aspects of your teaching.

Have clear, specific learning outcomes

Well-developed learning outcomes are vital to every aspect of teaching. Learning outcomes help instructors prioritize class content, activities, and assessments, and ensure students are aware of what they should know and how best to demonstrate that knowledge to you. Clear and specific learning outcomes are the first step to developing accessible and flexible classrooms. Ensure your learning outcomes are written in clear, understandable language.

Build in flexible measures of assessment for learning outcomes

Flexible measures of assessment allow learners to demonstrate content proficiency in a variety of ways. How can your students show that they have met the learning outcomes, and can they do this in different ways? For example, a learning outcome may be for students to demonstrate public communication skills. Many instructors would develop an assessment based on public speaking to assess this learning outcome. However, public speaking can provoke panic in many students, especially students who do not fit neatly into a model of neurotypicality. Additionally, public communication is not restricted to public speaking skill or ability. How can your students demonstrate public communication without necessarily requiring public speaking? Could they have the option to make a series of social media posts, or create a podcast to demonstrate this skill in a way that aligns with their strengths, interests, and future career paths?

Minimize construct-irrelevant factors in assessment

When assessing students’ understanding of course concepts, ensure you are testing the skills and knowledge students are learning in class by removing construct-irrelevant factors. Assessments by their nature require students to have additional knowledge outside of the specific skill or learning outcome being assessed. For example, a math exam may use word problems to assess students’ understanding of math concepts; however, the ability to read quickly and fluently is construct irrelevant. Students who are not as adept at reading, such as those with dyslexia or who are learning English, may miss important parts of the question even though they understand the underlying math concepts.

Ensure technology used in and outside of class is accessible

Not all technology is built with user accessibility in mind. Make sure to test any tools you are using to ensure that all of your students can use the technology tool or program, regardless of any access needs they may have (i.e. blindness, low physical mobility, etc.). Ensure any videos you show also have captions and/or a transcript, and that you describe images shown on slides. Don’t use color as your only indicator of difference. The Google Suite of products (e.g. Google Docs, Google Slides, Google Sheets) are known to be highly accessible and have appropriate tools/supports built in for those who need them.

Consider how each part of your curriculum might affect students of varying backgrounds and needs

Universal Design should be thought of as a way of approaching your curriculum design. Each of the UDL principles offers a way to start thinking about some common instructional “choke points.” For example, the Center for Universal Design’s fifth principle, Tolerance for Error, specifies that a given context should allow students to make mistakes without severe penalty. This might mean there are low stakes checkpoints for a larger assignment, such as draft review periods for final essays or no-penalty practice problem sets in advance of an exam. This approach allows you to help your students identify particular strengths and weaknesses before earning grades, but it also allows anxious students to practice in low-stakes situations.

Partner with students to develop and revise learning goals, experiences, and assessments, with accessibility in mind

When students take ownership of their learning and have agency within their learning environments, they are more engaged, interested, and likely to achieve higher standards. Students have a wealth of experiences that instructors can tap into in order to make courses more accessible. Students may be able to recognize inaccessible aspects of a course or assignment that instructors didn’t notice. Consider leaving an open class period to discuss feedback on the accessibility of the course, Canvas page, and other learning materials. You may also find that asking students to specifically reflect on their experiences with assessments or learning experiences can help you make them more accessible. You might consider asking students where they ran into challenges with specific assessments and what types of support would be helpful. This way, you can integrate these supports for all students in your course in the future.

Meyer, A., Rose, D., & Gordon, D. (2014). Universal Design for Learning: Theory and Practice. Wakefield, MA: CAST Professional Publishing

Text of above infographic

- Provide Multiple Means of Engagement to foster purposeful, motivated learners

- Provide options for self-regulation

- Promote expectations and beliefs that optimize motivation

- Facilitate personal coping skills and strategies

- Develop self-assessment and reflection

- Provide options for sustaining effort and persistence

- Heighten salience of goals and objectives

- Vary demands and resources to optimize challenge

- Foster collaboration and community

- Increase mastery-oriented feedback

- Provide options for recruiting interest

- Optimize individual choice and autonomy

- Optimize relevance, value, and authenticity

- Minimize threats and distractions

- Provide options for self-regulation

- Provide multiple means of representation, to foster resourceful, knowledgeable learners

- Provide options for comprehension

- Activate or supply background knowledge

- Highlight patterns, critical features, big ideas, and relationships

- Guide information processing, visualization, and manipulation

- Maximize transfer and generalization

- Provide options for language, mathematical expressions, and symbols

- Clarify vocabulary and symbols

- Clarify syntax and structure

- Support decoding text, mathematical notation, and symbols

- Promote understanding across languages

- Illustrate through multiple media

- Provide options for perception

- Offer ways of customizing the display of information

- Offer alternatives for auditory information

- Offer alternatives for visual information

- Provide options for comprehension

- Provide multiple means of action & expression to foster strategic and goal-directed learners

- Provide options for executive functions

- Guide appropriate goal-setting

- Support planning and strategy development

- Enhance capacity for monitoring progress

- Provide options for expression and communication

- Use multiple media for communication

- Use multiple tools for construction and composition

- Build fluencies with graduated levels of support for practice and performance

- Provide options for physical action

- Vary the methods for response and navigation

- Optimize access to tools and assistive technologies

- Provide options for executive functions

The “Plus One” Strategy

It can seem unmanageable to completely redesign all aspects of a course to achieve full UDL-alignment. Instead, while in the process of a course redesign, consider using the “plus one” strategy. Think about where students currently struggle in your class, or where barriers are present within your course, and consider how to reduce or eliminate them. Do you tend to get accommodations letters with similar needs each semester, such as extra time on exams or a distraction-free exam setting? How can you adjust your course to remove or diminish these barriers for all students? For example, can students still achieve the course learning goals with a take home exam? This modality change would eliminate access barriers and could even allow you to ask more probing, analytical questions on the exam to assess higher-order critical thinking skills.

Overall, when implementing the plus one strategy, consider: is there just one more way you can present information that would be helpful to students? One more way for students to demonstrate their knowledge or mastery of the learning goal? One more way to engage your students with the learning goals and course content? This easy to implement strategy allows you to gradually incorporate more UDL-based principles in your course, without requiring an entire course redesign from the onset. It also sets you on the path of developing a UDL and accessibility-focused course which will make incorporating more elements of UDL easier over time.