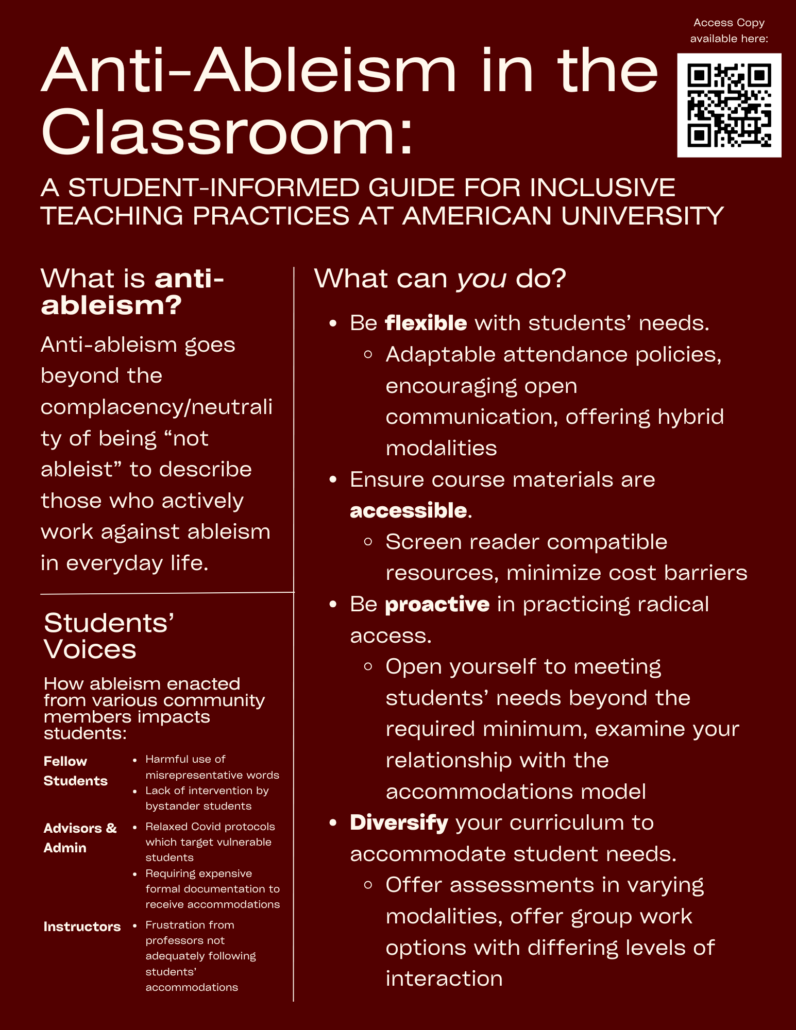

Anti-Ableism in the Classroom: A Student-Informed Guide for Inclusive Teaching Practices at American University

By Katelyn Lewicky (She/Her), Class of 2025

About This Project

Hi! My name is Katelyn Lewicky (She/Her) and I am a senior at American University majoring in Business Administration with a specialization in Marketing and a certificate in Disability, Health, & Bodies. I am also dual-enrolled in an MS in Marketing program here at AU, which I will complete after graduating with my Bachelor’s this upcoming Spring.

As a first-time Student Partner with CTRL it was important to me that I focus my project on two things I am passionate about: critical disability studies and teaching practices at American University. Following the disability studies coursework I’ve had the privilege of completing at AU my perspective on the student experience has shifted to focus largely on students’ access needs which are often not always adequately met in classroom settings. This project allowed me to work directly with students to uncover diverse perspectives on how ableism at American University affects one’s experience and I am eager to present this student-informed guide to incorporating an anti-ableist framework across teaching practices.

Accessibility in This Project

This project’s accessibility is enhanced by the inclusion of only two colors (a dark color for the graphic’s background with white text), the use of a simple sans-serif font, and a QR code linking to a software-readable access copy containing the same information as the graphic.

To expand access and uphold anti-ableist principles, I collected data for this project remotely, aligning with Universal Design for Learning (UDL) by accommodating participants’ diverse needs. Remote collection allowed people with mobility challenges, time constraints, or geographic barriers to participate fully. I offered varying levels of anonymity to encourage transparency and provided the option of verbal interviews for flexibility.

The Importance of Anti-Ableism at AU

1. What is Anti-Ableism?

I developed the following definition of anti-ableism (also found on the graphic) by combining existing scholarship with my own understanding: “Anti-ableism goes beyond the complacency/neutrality of being ‘not ableist’ to describe those who actively work against ableism in everyday life.”

This concept mirrors Dr. Ibram X. Kendi’s model of anti-racism defined in his 2019 book How To Be an Antiracist. Although the two concepts describe the radical fighting of different phenomena, they follow similar frameworks in that they both argue that we must actively work against the mistreatment of marginalized groups.

2. Students’ Voices on Ableism at AU

In addition to drawing on instances of ableism that I have observed firsthand at AU, I conducted a survey to gather experiences and perspectives from a diverse set of students on the matter. I received responses from students across all six schools of undergraduate education at AU. In developing my resource, I focused in particular on upperclassmen students who have attended the university for at least two academic years.

The survey aimed to explore students’ experiences of ableism enacted by three distinct groups at the university: peers, advisors and administrators, and instructors. Below, I summarize how respondents described and interpreted their experiences of ableism in interactions with these constituencies across campus.

Ableism from Fellow Students

Survey respondents emphasized feelings of anger and unsafety resulting from hearing their peers use derogatory language pertaining to disability. Some students explained that these instances only reflect poorly on those using the offensive language, while others feel shame for their peers and a larger disconnection from the university community due to mass amounts of complacency.

Ableism from Advisors & Administration

Survey respondents felt the most strongly about their negative experiences with advisors and administration, far more than those involving fellow students and even instructors. Students explained various ways in which American University’s Academic Support and Access Center (ASAC) failed them, including but not limited to the following:

- Relaxed Covid protocols which result in many students being left vulnerable to potentially detrimental illness on short notice

- Inadequate counselor availability

- Systems in place which require expensive and time consuming resources to be obtained before becoming eligible for necessary accommodations

- Accommodations only being provided for needs which ASAC has worked with before and already has protocols to accommodate

One student shared with me that “[the] instances that I have experienced the most ableist rhetoric are with the Disability Access Center.” This anecdote mirrored themes of multiple other responses in that the student feels the institution that AU has in place to protect students facing ableism in academia (ASAC) actually causes them more harm than good.

Ableism from Instructors

Survey respondents had mixed opinions on professors’ general handling of access and ableist issues at AU. Some students shared that their professors will make efforts to accommodate them when AU as an institution fails to and others identified professors as holding the most potential to harm their interactions with these issues. Notable student examples of how instructors could better accommodate them day-to-day include

- Eliminating inaccessible (physically, financially, etc.) field trips

- Removing required class participation,

- Creating less stressful testing environments

- Taking “extra steps” to accommodate a student (e.g., uploading presentation slides to Canvas following student requests).

3. How to Be Anti-Ableist

The four suggestions on practicing anti-ableism that I offer in this graphic are only the beginning. Being anti-ableist especially in an academic setting means practicing radical access and working to be accessible to all students as a baseline to how instructors interact with them.

Flexibility comes down to instructors’ willingness to meet students where they’re at and give them resources to succeed. This looks like: adaptable attendance policies, maintaining channels of open two-way communication, offering hybrid modalities when at all possible, and much more. Flexibility allows students to channel more energy into learning and achieving high standards, rather than navigating unnecessary barriers.

Material Accessibility encompasses all aspects of minimizing barriers to course materials. This spans from ensuring assigned texts are screen-reader compatible to providing free, reduced-cost, or sliding-scale purchasing options for course materials and more. For further guidance, instructors can refer to the CTRL’s own Accessibility Guide.

Proactive participation in a radical access model requires a shift in mindset from meeting the required minimum level of accommodation for specified students to actively working to reduce access barriers for all students. Instructors can educate themselves on the reactive model of reasonable accommodation as a first step to confronting access biases and shifting to a proactive approach. Universal Design for Learning (UDL) offers a framework for creating inclusive learning environments, and instructors can explore the CTRL’s UDL Resource Guide for specific guidance.

Diversifying curriculums to better accommodate student needs involves the evaluation of who traditional assessment methods benefit and how the playing field can be leveled. It is also beneficial for students to have autonomy over aspects of their learning (e.g., offering options for individual, partner, and group work on a rotating schedule to equitably suit all students’ needs).

Additional Resources

There are several resources available to educate instructors (and beyond) on anti-ableism in and outside of the classroom! These are some of my favorite recommendations: