About

Heads of Women

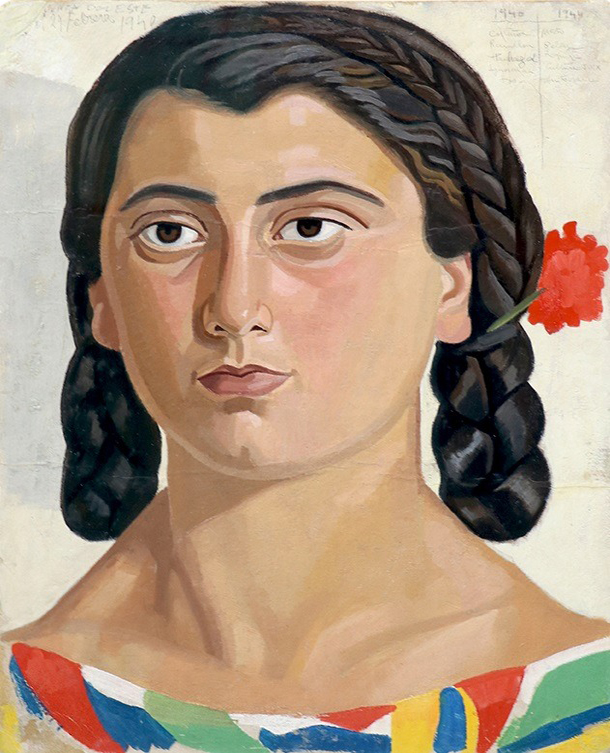

The Heads of Women series consists of at least thirteen known portraits of women representing a wide range of different skin tones, hair color, eye color, and facial features. For example, Head of Woman (1941) represents a woman with pale skin, blue eyes, and light brown hair (Figs. 3 and 4), while Head of Black Woman (1946) likely depicts an Afro-Brazilian woman with dark brown skin and an afro (Figs. 5 and 6). In other cases, women appear to be mixed-race, such as the ones featured in Head of Blonde Woman (1951) and Argentina (1952) (Figs. 12 and 14). The former has almond-shaped eyes, while the latter presents a striking contrast of blonde hair and dark skin. Sketch for Head of Woman (1940-1944) is the only representation by Mallo of a woman whose features and hairstyle evoke the indigenous community (Fig. 15); therefore, I have decided to include it as part of the series, even if it is considered a preparatory drawing that she might have used as a method of study or as a way to develop her ideas (it contains annotations and it was made on cardboard instead of on canvas). Each woman is presented frontally or in strict profile, and Mallo’s use of clear contour lines, contrast of light-and-dark, and mindful approach to color invest the figures with a sculptural quality. However, their delicately arranged hairstyles are all different.

The paintings that comprise the Heads of Women series have never been exhibited or reproduced together.[1] Who Mallo hoped would specifically see this work remains unknown. While the artist was alive, they were exhibited in pairs or in groups, in formal exhibitions, or in the pop-up presentations that she organized in hotel rooms. It should be noted that the artist’s main income came from her artistic production. She both worked for clients who commissioned her work and painted on speculation in the hope that people would buy them. In fact, she claimed “not to paint for exhibitions,” meaning she did not create individual works, or groups of works, thinking of possible future exhibitions.[2] Her concern was selling the paintings she produced. Therefore, once the Heads were sold, it became difficult to reunite them. However, Mallo did create reproductions for broader distribution; for instance, some of the Heads were pictured on postcards or reproduced in the Argentinean magazine Para Ti. Mallo probably did not conceptualize Heads of Women as a series from the beginning; instead, they look like the result of her abiding interest in the human figure and on issues of race and female beauty for more than a decade. In this regard, we cannot be certain either about the number of Heads that the artist planned to paint or the number that she finally painted. The thirteen examples considered here are the only documented works of the kind, and their existence in public or private collections has been proved through photographs, yet Mallo mentioned in an interview that took place in 1979 in Spain that a collector bought from her “treinta y tantas cabezas” [over thirty heads].[3]

In the same interview, Mallo stated that she also painted men’s heads while in Argentina, but that she could not photograph these works before she returned to Spain. Curiously, none of those “heads of men” have been found, with the exception of the interesting and undated preparatory drawing titled Retrato de hombre con escala de colores [Portrait of a Man with Color Scale] that was exhibited at the Galería Guillermo de Osma in Madrid in 2017 (Fig. 40), and some sketches that she made in Galicia before going into exile.

Although it is possible that Mallo painted more Heads than the ones currently known, and that she also included some men as part of this series of portraits, I believe that she privileged women—as she also did in other contemporaneous works. Indeed, as noted by Shirley Mangini, in the 1940s, Mallo tended to paint only female figures, “gradually replac[ing] her socialist subject matter with a language that exalted the female body: feminine oceanic motifs and mythological female figures.”[4] This trend aligns with Mallo’s constant efforts to find her own place in socio-cultural contexts not particularly favorable to women, neither in her native Spain nor in Latin America. In the former, where she lived from 1902 to 1937, she had to deal with a highly sexist and patriarchal environment that privileged male artists and still assigned women the primary role of guardians of a marriage and the house.[5] In Buenos Aires, where Mallo lived from 1937 to 1965, the cultural sphere was also ruled by men. As explained by her friend Victoria Ocampo when talking about her own experience as a young woman in Argentina,[6] “women’s desire to educate themselves was against God’s will, and the same happened with other innocent freedoms and innocent pleasures.”[7] Ocampo, who channeled her defense of the intellectual potential of women through the creation of the cultural magazine Sur, was much more direct than Mallo on her feminist beliefs and her approach to gender issues. However, the Spanish artist expressed her ideas on femininity nonetheless, giving them expression in painting while Ocampo did so in writing. In the same manner that I claim Mallo’s Heads of Women was a visual statement on race and ethnicity, I also claim that her preference for the female figure in the Heads series was a statement on women and, as a whole, the series thus testified to intersectionality as a fundamental strength of Latin American cultures.

Figure 3. Cabeza de mujer, frente [Head of Woman, front] 1941. Oil on panel, 56 x 44 cm.

© Maruja Mallo

Figure 5. Cabeza de mujer negra, perfil [Head of Black Woman, front] 1946. Oil on canvas, 56.5 x 46.5 cm. © Maruja Mallo

Figure 7. La cierva humana, frente [The Human Deer, front] 1948. Oil on canvas, 55.5 x 45 cm. © Maruja Mallo

Figure 9. Silhouette of Polinesia, frente [Polynesia, front] 1951. Unknown technique, 56 x 44 cm? [9]

Figure 11. Mujer rubia or El Campeón [Blonde Woman or The (Male) Champion] 1951. Oil on panel, 49 x 40 cm. © Maruja Mallo

Figure 4. Cabeza de mujer, perfil [Head of Woman, profile] 1941. Oil on panel, 56 x 44 cm.

© Maruja Mallo

Figure 6. Silhouette of Cabeza de mujer negra [Head of Black Woman, profile] 1946. Unknown technique, 56 x 46 cm.[8]

Figure 8. La cierva humana, perfil [The Human Deer, profile] 1948. Oil on canvas, 56 x 46 cm.

© Maruja Mallo

Figure 10. Polinesia, perfil [Polynesia, profile] 1951. Oil on canvas, 55 x 43 cm. © Maruja Mallo

Figure 12. Oro [Gold] 1951.

Oil on canvas glued on panel

51 x 40 cm. © Maruja Mallo

Figure 13. Joven mujer negra [Young Black Woman] 1948. Oil on cardboard, 47 x 38.5 cm.

© Maruja Mallo

[1] With the upcoming publication of Maruja Mallo’s catalog raisonné they will all likely be reproduced together.

[2] Maruja Mallo, Mentor. Revista Uruguaya Ilustrada, January 1943. Press clipping, Archivo Maruja Mallo.

[3] Once that Mallo returned to Spain and began to be “rediscovered” by the Spanish public, she tended to aggrandize some of her achievements or to talk about her life in a grandiloquent way, especially when dealing with her American period, so it would not be surprising that she exaggerated a little bit about the collector that bought her “more than thirty heads.” Maruja Mallo. “Imágenes. Artes visuales: Maruja Mallo.” Interview by Paloma Chamorro (August 4, 1979). Video, RTVE Archive.

[4] Mangini, “From the Atlantic to the Pacific,” 94.

[5] Although I do not consider Maruja Mallo to be a Surrealist, I do recommend Ellory Winona Schmucker’s analysis of the peculiar and nuanced role of women in Surrealism and the Spanish avant-garde, in which this author also analyzes Mallo’s contributions: Ellory Winona Schmucker, “Maruja Mallo: la realidad femenina dentro del Surrealismo en España.” Master’s thesis, University of South Carolina, 2010.

[6] Victoria Ocampo (1890- 1979) was an Argentinean feminist writer, intellectual and patron of the arts who founded the acclaimed cultural magazine Sur, in which Mallo herself published one of her most important texts: “Lo popular en la plástica española a través de mi obra, 1928-1936.”

[7] Victoria Ocampo, Testimonios. “Novena serie, 1971/1974,” Sur (1975): 232. Quoted in Maria Victoria Streppone, “La construcción de modelos femeninos de Victoria Ocampo entre 1920 y 1940: reconsideraciones sobre Margherita Safartti y Virginia Woolf,” Historia Crítica no.67 (2020): 114.

[8] An image of Head of Black Woman (profile, 1946) will likely be published for the first time in the upcoming catalog raissoné devoted to Maruja Mallo’s pictorial work. For reference, see figure 37, in which Maruja Mallo appears posing next to this painting. Silhouette done from a black-and-white reproduction of the painting accessed thanks to the courtesy of gallerist Guillermo de Osma.

[9] An image of Polynesia (front, 1951) will likely be published for the first time in the upcoming catalog raissoné devoted to Maruja Mallo’s pictorial work. Silhouette done from a black-and-white reproduction of the painting accessed thanks to the courtesy of gallerist Guillermo de Osma.

Web design: Esther Rodríguez Cámara, 2021