HOME › PART 2: Painting for Equality › Painting vs. Ethnography

Painting vs. Ethnography

One of the most peculiar characteristics of Mallo’s Heads of Women is the fact that many of the paintings comprise pairs of frontal and profile views. Such is the case in Head of Woman (1941), Head of Black Woman (1946), The Human Deer (1948), and Polynesia (1951). Gold (1951) and The Champion/Head of Blonde Woman (1951) may have been conceived as a pair, too, but both heads appear in profile. It is uncertain if Mallo ever did a corresponding profile for Sketch for Head of Woman (1940-44), Argentina (1952), and the frontal view of Young Black Woman (1948).

In Marta Penhos’ discussion of the pairing of frontal-and-profile portraits, she pointed out that this typology witnessed from the 19th century the coalescence of two traditions: Renaissance artists’ desire to represent pictorial reality in a faithful way and the tradition of scientific images.[1] Since the Renaissance, printed treaties on anatomy were available, including drawings of classifications and typologies, and artists began to study the human body through these kinds of images.[2] Proportions were also given particular attention by art theorists, and also cosmologists and astrologists, as a way to understand how the macrocosm of the universe “reveal[ed] its ‘divinely’ ordered beauty in the microcosm of man.”[3]

By contrast, from the 18th century through the first decades of the 20th century, the front-and-profile typology was introduced in other fields, such as philosophy, criminology, and anthropology, to show “deviations” from established “norms.”[4] Photography played a fundamental role in this development because, as noted by Allan Sekula, “[it] came to establish and delimit the terrain of the other, to define both the generalized look—the typology— and the contingent instance of deviance and social pathology.”[5] In particular, the front-and-profile typology in photography helped to establish differences (and hierarchies) in terms of race, social and health conditions.[6] For instance, at the end of the 19th century, this typology was used in connection with ideas of criminality, as in Galería de ladrones conocidos [Gallery of Known Thieves], published by the Buenos Aires Police Department in 1904. [7] (Fig.62) Marta Penhos noted that a collective agreement signed by the South American police corps in 1905 stated that facial photographs of individuals should be taken in frontal and profile pairs, in plaques of the same size, and from a uniform distance that enabled consistency across all images.[8]

In the late 19th century, some communities of Afro-Brazilians that would later interest Mallo had already captured the attention of “ethnographic photographers,” such as the images of women taken by the German-Brazilian photographer Alberto Henschel (1827-1882). He dedicated special attention to the cafuzos of the Pernambuco region (the mixed-race group that Mallo referred to as the epitome of beauty) and presented the women as sensuous, with some garments and ample cleavage. One of his cafuza women became a Brazilian icon and was later reproduced in publications and advertisements (Fig. 63). Mallo’s Head of Black Woman (front and profile, 1946) features a hairstyle that bears a visual relationship to women of that ethnic group.

Years later, the anthropologist Edgard Roquette-Pinto (1884-1954), who pursued his research under the auspices of the National Museum of Brazil, continued working in this tradition.[9] In the words of Sebastião Vanderlei de Souza: “Roquette Pinto was also the first anthropologist of the country to develop a systematic research project about the morphological characteristics of the different ‘racial types.’”[10] At the end of his Notas sobre os typos antropológicos do Brasil, Roquette Pinto followed the example of German anthropologist Eugen Fisher by including photographs of diverse Brazilian “racial types” photographed frontally and in profile. For Roquette-Pinto the cafuzos represented a very small percentage of the population and therefore he did not include them in any of his major classifications. Nevertheless, he photographed them. (Fig. 64)

Ironically, Roquette-Pinto was interested in disproving biological understandings of race and demonstrating that mixed-race people were not “degenerated types” nor “inferior.” In this way, he was annulling the idea that Brazil’s “national problems were due to the anthropological characteristics of [its] population.”[11] However, even if he had laudable intentions, he kept employing a practice associated with racist thought (ethnographic photography) that reduced people to their bodies and suggested that these forms could reveal information about their intellect.

Mallo, too, employed this controversial typology. Indeed, discussion of her work cannot avoid the topic of ethnographic photography, especially because the artist herself wanted to explore the different cultures of Latin America. Crucially, Estrella de Diego has pointed out that Mallo’s series Naturalezas Vivas seems to represent the notebook of a traveler who felt the desire to depict the underwater wonders that she encountered and to be able to take their images home as souvenirs. She compared what Mallo did in that series with “the botanical procedures of those large English expeditions of the 18th century [which] took note of the strange, the foreign, of everything that everybody, if only narrated, would take as a trick of the imagination.”[12] I believe that Mallo not only approached her Naturalezas Vivas with this “exploratory,” scientific, and documentary impulse but that she also broached her Heads in a similar way, with a certain mix of anthropological and artistic curiosity. In this sense, to an extent, she was reproducing the attitude of those colonial explorers whose work “othered” Indigenous populations.

For instance, when we take a closer look at how the women’s hair is pictured, we see that it is drawn with the same rigor as the shells, corals, and algae that are part of her Naturalezas Vivas series (Fig. 65). As we have also discussed in relation to pictorial Brazilian precedents, in the case of some of her Heads (Sketch for Head of Woman 1940-1944, Young Black Woman 1948, The Human Deer 1948, Polynesia 1951) Mallo associated women of color with nature, including elements like a flower, leaves, or a circular motif reminiscent of a female deer’s ears in her compositions. In the case of The Human Deer, the title itself is telling about the visual connections Mallo drew between Black and mixed-race women and nature.[13]

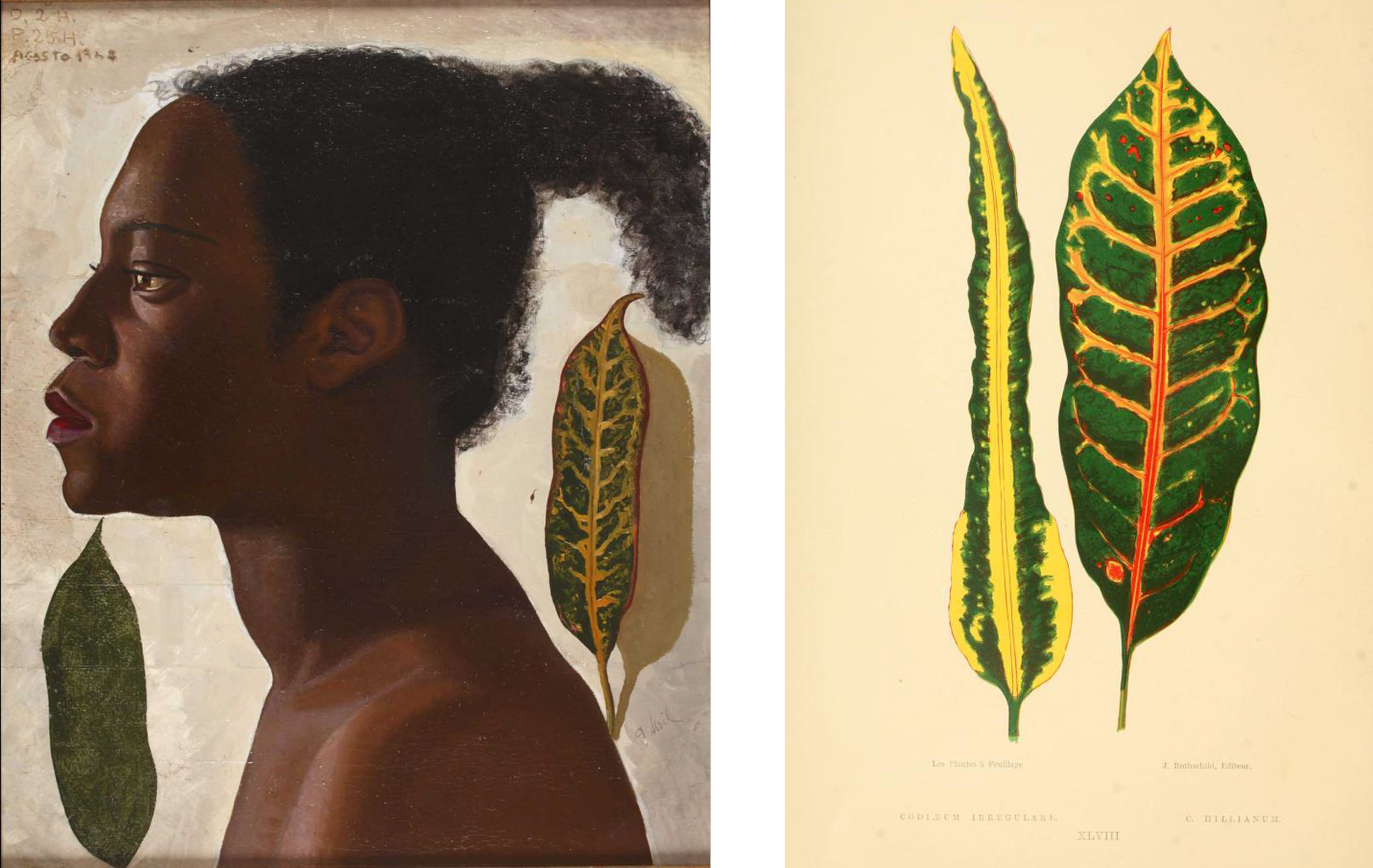

In the case of Young Black Woman (Fig. 66), the inclusion of two big croton-like leaves next to the subject’s face, and the way in which the profile figure highly contrasts with the background, clearly resembles those botanic illustrations of newly discovered natural specimens done by European and American expeditionaries during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in Latin America and the Philippines.[14] Similarly, in Polynesia (1951), the placement of little leaves around the woman’s neck recalls those visible in the photograph of Moça cafuza by Alberto Henschel of c. 1869. (Fig. 67)

In the case of the only Caucasian woman depicted in the series, Head of Woman (1941), these kinds of elements are not included, which prompts one to think that Mallo presented white women as more “civilized” or less connected to nature than women of other races. However, when we compare Head of Woman (1941) with Head of Black Woman (1946) and Argentina (1952), which respectively feature a White woman, a Black woman, and a mixed-race woman with Asian traits, we can appreciate that they exhibit a comparable pictorial treatment and are presented as equally glamorous in terms of their makeup, lighting, and hairstyle. None of them, furthermore, include natural elements. Although the only woman that is most closely depicted in the manner of a botanical illustration is Black, Mallo depicted a white man from her native Galicia in a similar way in order to compare the scale of his head and these natural elements (Fig. 68). Further, the drawing bears a clear compositional similarity to Young Black Woman (1948). This, as well as my explanation on Mallo’s interest in relating the geometry of the human body with that of nature (see Part 1), suggests that Mallo’s ideas about race were quite fluid and complex. Thus, we can neither directly affirm that the woman in this latter painting was intended by Mallo to be seen as more rural, natural, or backward than the rest of her Heads just because she is depicted next to two natural elements nor we can disregard some of the artist’s implicit bias about Latin American racial diversity and the connotations of her pictorial decisions that we have commented on.

Furthermore, the fact that Mallo made a series of paintings instead of a photographic series, partially counteracts the relationship between the Heads and ethnography and aligns them with the frontal-and-profile typology’s other source—namely, the Renaissance and its artists’ interest in conveying beauty through the use of harmonious proportions. The women’s fashionable makeup and hairstyles distance them from criminal photography, a practice in which glamour was not the professed goal. To some extent, Mallo essentialized her subjects for “positive” ends, instead of for “negative” ends, as that kind of photography did.

Figure 62. Minga-Minga, 1904. Galería de ladrones conocidos. Centro de Estudios Histórico Policiales “Francisco Romay,” Policía Federal Argentina, Buenos Aires, 1904.

Figure 63. Alberto Henschel. Portrait-Cafuza, c.1869.

Figure 64. Roquette-Pinto. Photograph of a ‘Cafuzo’ (1929).

Figure 65. Press clipping showing Maruja Mallo’s Head of Black Woman (1946) and Vibrant Life in La Prensa, Buenos Aires, November 14, 1948, with the occasion of Mallo’s exhibition at Carstairs Gallery in New York that year.

Figure 66. Left: Maruja Mallo. Young Black Woman, 1948. Oil on cardboard, 47 x 38.5 cm. © Maruja Mallo. Right: Illustration of Codiaeum Irregulare , included in E.J. Lowe’s Les plantes a feuillage coloré: histoire, description, culture… (Paris: Rothschild,1867-1870).

Figure 67. Left: Maruja Mallo, Polynesia (profile, 1951). Right: Alberto Henschel. Moça-Cafuza (cropped), c.1869.

Figure 68. Maruja Mallo. Man and Fish, Galicia Notebook, 1936. Pencil on paper, 21 x 26 cm. Archivo Maruja Mallo.

[1] Marta Noemí Penhos, “Las imágenes de frente y de perfil, la ‘verdad’ y la memoria. De los grabados del Beagle (1839) y la fotografía antropológica (finales del siglo XIX) a las fotos de identificación en nuestros días,” Memoria y sociedad 17, no. 35 (2013): 23.

[2] Marta Noemí Penhos, “Frente y Perfil. Una indagación acerca de la fotografía en las prácticas antropológicas y criminológicas en Argentina a fines del siglo XIX y principios del XX,” in Arte y Antropología en la Argentina by Marta Penhos et al. (Buenos Aires: Fundación Espigas, 2005): 37.

[3] James L. Hutson Jr., “Renaissance Proportion Theory and Cosmology: Gallucci’s Della simmetria and Dürerian Neoplatonism,” Storia dell’arte no. 125/126 (2010): 26.

[4] Penhos, “Las imágenes de frente y de perfil,” 23.

[5] Allan Sekula, “The Body and the Archive,” October 39 (Winter, 1986): 7.

[6] Penhos, “Frente y Perfil,” 42.

[7] Diego Galeano, “Travelling Criminals and Transnational Police Cooperation in South America, 1890-1920,” in Voices of Crime: Constructing and Contesting Social Control in Modern Latin America, edited by Luz E. Huertas, Bonnie A. Lucero, and Gregory J. Swedberg (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2016): 23. To read more on the relationship of the front-and-profile and the criminal body see Allan Sekula, “The Body and the Archive,” October 39 (Winter, 1986): 3-64.

[8] Penhos, “Frente y Perfil,” 32-33.

[9] Sebastião Vanderlei de Souza, “Retratos da nação, os ‘tipos antropologicos’ do Brasil nos estudos do Edgard Roquette-Pinto, 1910-1920.” Boletim do Museo Paraense Emílio Goeldi. Ciências Humanas 7, no. 3 (2012): 647.

[10] My translation. Original text in Portuguese: “Roquette Pinto também seria o primeiro antropólogo do país a desenvolver um sistemático projeto de pesquisa sobre as características morfológicas dos diferentes ‘tipos raciais.’” Souza, “Retratos da nação,” 647.

[11] Souza, “Retratos da nação,” 665.

[12] My translation. Original text in Spanish: “Un poco como ejercicio de botánico a la manera de las grandes expediciones inglesas del XVII: dar cuenta de lo extraño, de lo extranjero, de aquello que todos, simplemente narrado, tomarían por una trampa de la imaginación.” Diego, Maruja Mallo,109-110.

[13] The Human Deer (front and profile, 1948) was sent to the First Hispano-American Biennale of Art, held in Spain in 1957 and inaugurated by Franco on “The Day of the Race.” Curiously, although Mallo had been working in Argentina for years, her painting was included in the galleries devoted to Spain. As noted by Francisco Godoy, “while in 1951 Franco inaugurated the I First Hispano-American Biennale of Art, the I São Paulo Biennial opened too. While at one side of the Atlantic an internationalism breaking its ties to the [Iberian] peninsula was reclaimed, in the other there was a call to a Hispano-American unity that perpetuated the bonds with the colonial tradition.” My translation. Original text in Spanish: “Mientras en 1951 Franco inauguraba la I Bienal de Arte Hispanoamericano en Madrid, se abría también la I Bienal de São Paulo. Mientras a un lado del Atlántico se reivindicaba un internacionalismo que rompía con los lazos directos a la península, por el otro se llamaba a una unidad hispanoamericana que perpetuaba los lazos con la tradición colonial.” Francisco Godoy Vega, La exposición como recolonización. Exposiciones de arte latinoamericano en el Estado español (1989-2010) (Badajoz: Fundación Academia Europea e Iberoamericana de Yuste, 2010), 56, footnote 119. Mallo’s decision to send the Human Deer could be seen as a perpetuation of this tradition, as this pair of paintings most frames Blackness as exotic.

[14] To read more on this kind of botanical expeditions see Daniela Bleichmar, Visible Empire: Botanical Expeditions and Visual Culture in the Hispanic Enlightenment. University of Chicago Press, 2012.

Web design: Esther Rodríguez Cámara, 2021