HOME › PART 1: The Search of Ideal Beauty › The Glamour of Diversity

The Glamour of Diversity

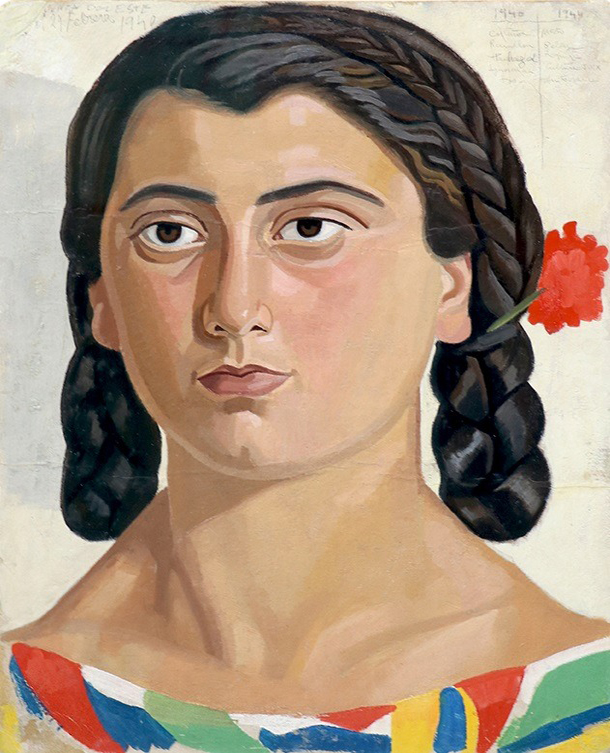

Apart from Mallo’s investment in the human form, developed through years of rigorous training and a deep interest in geometry and mathematical proportions, Heads of Women also betrays the artist’s attraction to a more contemporary iteration of female beauty. In this series, Mallo interrogated certain female beauty standards of the 1940s and the beginning of the 1950s in Buenos Aires, which were in turn a reflection of the influences coming from Hollywood and North America. Therefore, to generate this collective portrait of Latin American diversity, she also attended to women’s makeup and hairstyles. Most of the Heads feature carefully nuanced complexions, contoured red lips, thin well-defined eyebrows and elaborate, and carefully drawn hairstyles.[1]

By employing the kind of glamorous look that was promoted by modern cinema and contemporary magazines, and by evoking the lightning styles typical of studio photography, I suggest that Mallo attempted to posit all ethnicities as equally glamorous and beautiful. As her friend Gómez de la Serna once noted, the artist was “cineástica [2] and modern,”[3] and she indeed infused those qualities into her ideal female archetypes.

Mallo’s interest in cinema came from her formative period in Madrid, where she and many of her contemporaries of the Spanish avant-garde were influenced by the charm of silent movies. During that time, she discovered classic films that inspired her to create different artworks featuring cinema-related themes.[4] (Fig. 32) As noted by Judith Nantell, “for many in Mallo’s generation, the cinema would not merely serve as an emblem of the modern [,] it also would become ‘the eye’ of the century because, as Francesco Casetti would explain years later, the camera ‘captured what lay before it . . . in the spirit of the time.’”[5] This attitude perfectly aligns with Mallo’s ideas regarding the necessary elements for a true artistic revolution in the twentieth century. According to the artist, art has a social function, and it can be considered revolutionary if able to react against a damaged society.[6] However, for her, art needed much for than new formal techniques to be revolutionary. She thought that “what really makes art new and comprehensive, apart from solid scientific knowledge and skill, is the implementation of a new iconography for a living religion [and] a new order.”[7] Thus, the ideas about women and the beauty standards that were promoted by American cinema gave her a legible iconography that enabled her to assert the beauty of Latin American diversity.

Furthermore, taking into account that Mallo herself acknowledged that she owed much to cinema,[8] it is likely she fostered this interest once she went into exile in Buenos Aires and made the city her permanent residence. As a metropolis with a population of two million, Buenos Aires was exposed to the latest technological developments and entertainment advances coming from North America. One of those novelties was the evolution of cinema, especially the spread of movies with sound, which appeared in Argentina in 1931.[9] Based on data from the U.S. Commerce Department, Matthew Karush notes that, in Buenos Aires, they were already 152 movie theaters in 1929. [10] Further, he explains that, during the 1930s, Hollywood films were favored by people of all social classes, while Argentinean movies were usually watched by a middle or lower-class audience.[11] In fact, during the late 1930s and 1940s, many Argentinean films aligned with the ideology of Juan D. Peron, the general and later president of Argentina, praising the humility and novelty of poor hardworking people and the nation’s rural past.[12] While Argentinean films were used as a political tool by Juan D. Perón, foreign movies seem to have been perceived as more closely connected to the glamour of Hollywood.

During the 1930s and 1940s, the relationship between Hollywood cinema and makeup was especially strong. Jennifer H. Miller argues that films explicitly promoted “glamour as an integral part of women’s identity, thereby naturalizing the links between femininity and cosmetics.”[13] Film producers were aware that perfect hair and makeup were qualities that most contributed to a star’s iconic status and paid special attention to it. [14] Beyond the film set, as pointed out by Mary Desjardins, fan magazines served as the link between stars and the consumer industries that employed them as images to sell their products to a predominantly female audience. This strategy is what led to women’s interiorization of those glamorous images as the ideal of beauty.[15]

Hollywood-related glamourizing trends of the 1940s had a global impact and directly influenced the way that female beauty was seen in the Hispanic world too. One of the most popular magazines on cinema written in Spanish was Cinelandia, edited in Hollywood but also commercialized in Latin American countries and in Spain from the 1920s to the 1940s. In figure 33, we can see an image of actress Kay Francis (1905-1968) gracing the cover of a 1940’s issue of this publication. As noted by Mary Desjardins, Francis was one of the Hollywood actresses who was most widely promoted in fan magazines, in which it was common to find stories emphasizing the role played by fashion and cosmetics in the successful careers of film stars. [16]

Paralleling the growth of the film industry both in Hollywood and in Argentina, a series of magazines dedicated to the entertainment world and its stars became popular in Buenos Aires, too. As in the previously mentioned example of Cinelandia, studio photographs and illustrations influenced by the aesthetics of cinema were commonly used for their covers and interior pages of Argentinean magazines. Three of the most popular ones dedicated to entertainment were Sintonía (Fig.34), Radiolandia, and Antena.[17] The cover images of these publications shared aesthetics with those magazines that were even more directly targeted to women and that generally covered a wider arrange of issues, such as fashion, art, architecture, music, decoration, reviews on books, recommendations for travel, etc. Among the latter, are Para Ti, Rosalinda, Maribel, Vida Femenina, Vosotras, Chabela, Estampa, Selecta, and Damas y Damitas.[18]

Maruja Mallo developed strong connections as a designer and subject for some of these publications,[19] which is understandable since the editorial industry was a common source of work for Spanish intellectuals exiled in Argentina and Mexico.[20] For this and other magazines, Mallo designed covers and illustrations; in others, she was interviewed or her work was reviewed.[21] In Para Ti, some of Mallo’s paintings were reproduced, including at least four of her Heads: Head of Woman, front (1941), The Human Deer, front (1948), Blonde Woman/The Champion (1951) and Argentina (1952), often with short texts (Fig.35). For example, in the case of Argentina (1952) the accompanying text read:

We are here introducing the latest work by the great Spanish painter Maruja Mallo, resident in Buenos Aires (…) Its impressive coloring, the magic of chiaroscuro, its restrained expression, [and] the beauty and grace that affect all [its] details reach their highest point in this artwork, leading to a difficult and admired perfection.[22]

Mallo not only collaborated with the editors and staff of these kinds of magazines, but images from her Heads of Women series were influenced by the aesthetics of its covers. For example, as first noted by Amelia Meléndez, formal connections are evident between Mallo’s Heads and Raúl Manteola’s covers for Para Ti (Fig. 36), D. Federre o Moraga’s covers for Maribel and Rodolfo Claro’s covers for El Hogar.[23] Indeed, the women in all of these colorful illustrations or photographs are depicted in “close-up” akin to the convention in widespread use in Hollywood.[24] This “close-up” trend might have been related to the US Motion Picture Production Code, which from 1934 established a series of moral standards that rejected full nudity and any sensual representation of the body.[25] Furthermore, the close-up was also used in film to aggrandize the figures and make them appear more formidable.[26] A similar effect was achieved by Mallo in her Heads, which despite being painted on relatively small canvases look “massive,” as described by Shirley Mangini.[27] Their exaggerated scale is evidenced in a photo in which Mallo posed next to Head of Black Woman (profile, 1946) on the occasion of her 1950 Paris exhibition (Fig. 37). However, more than the actual size of the women’s heads, it is the especially narrow space between them and the border of the canvas that makes the canvases’ subjects read as so especially large.

One of the famous close-ups of Gone with the Wind, that of actress Vivien Leigh wearing an iconic red dress in the role of Scarlett O’Hara, has clear similarities with both Head of Woman (front, 1946) and Argentina (1952). (Fig. 38) Mallo likely saw this film, for it premiered to great fanfare in Buenos Aires on September 25, 1940. Another film that deployed close-up footage was Carl Dryer’s La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (1928) which Mallo probably watched too because, while enjoying a sponsored period of artistic training in Paris in 1931-32, she studied film scenography with Jean and Valentine Hugo, who were responsible for the costume and set design of this film.[28]

Mallo not only experienced the iconic beauty of film actresses on the screen and, as we have seen, in printed publications, but she also met some of the popular stars of her moment. As she moved through the aristocratic circles of Buenos Aires, Montevideo, and some other holiday destinations, she often encountered actresses known for their beauty. For example, in a magazine clipping of 1945, she appears in several photos with actresses Jacqueline Delubac, Florence Marly, Lisette Chambard, Margarita Kenny, and Helene Carosio.[29]

Photos of Mallo from different points in her life also reveal the importance that she placed on personal appearance.[30] In fact, as Patricia Mayayo rightly argued, Mallo’s public image always was an essential part of her artistic project.[31] When she was young she began to wear red lipstick and particularly adorned her eyelashes with heavy mascara. In the last decades of her life, once she came back to Spain from exile, she tended to use intense blue eye shadow on her eyelids and colored her hair (Fig. 39). However, she did not randomly choose a tone, evidenced by a remark to her friend María Escribano at an exhibition opening in 1975 specifying that her hair color was a precise shade: “Venetian Blonde.”[32] As with hair, she had a clear vision of the significance of makeup as an artistic tool. In her 1979 interview for Spanish public television, she claimed that makeup “plastifica la cara” [makes the face artistic] and that a face without it seems to be washed-out because makeup contours and, by doing so, it accentuates facial features.[33]

If Mallo paid so much attention to this apparently superficial aspect of external appearance it must be because she thought that one’s personal appearance had an impact on the viewer and was a mode of self-fashioning. She was also probably aware of the role of cosmetics in shaping ideas about race and gender too. In the case of makeup, it can even be considered a “social technology.” As argued by Jennifer H. Miller:

It is more typical to think of makeup as fundamentally decorative, a means of adornment. Also, in keeping with this conventional view, both makeup and makeup practices have historically been tied to the bodies of women and the representation of the female body-particularly the female face. This understanding of cosmetics has created a blind spot when it comes to looking at makeup; it has precluded seeing makeup as a social technology in favor of seeing it as decoration or mere style.[34]

In the Heads series, paint and makeup became almost the same thing, as Mallo applied colors to the Heads similarly to the way foundations and shades are used to contour the face and accentuate its volumes. Her unfinished preparatory drawing Portrait of a Man with Color Scale allows us to understand how she approached the application of color to the canvas in her female Heads (Fig. 40). As we see in this example, Mallo planned each color that was meant to be used for the man’s face and meticulously included painting samples of different earthy tones, yellows, and purples. She probably used yellows in the lighter parts of the face and purples in the shadows as they are complementary tones and generate a harmonic result, which was always one of Mallo’s goals. In other drawings of heads, like the ones in figures 16 and 23, she also annotated lists with those facial features that she intended to paint with light colors and with dark tones. In Heads of Women, both in cases in which light is more diffuse (like in Head of Woman, 1941) and in those with a stronger contrast between light and shadow (like in Argentina, 1952) color is applied flatly in sections that help to define basic volumes. Those sections were then likely blended with the brush to achieve a sense of polished skin.

The way that Mallo applied color to her Heads paralleled makeup theories that had been developed by Max Factor in the US in connection with the film industry and that had global echoes from that moment on.[35] In 1918, Factor introduced “the color harmony” principle into makeup, which stated that “makeup was supposed to synchronize with coloring, where ‘coloring’ was understood to include complexion, hair color, and eye color.“[36]

In Head of Woman 1941 (front and profile) we see that the woman features the typical makeup of the 1940s: a very natural foundation with a pinkish hue, rosy blush, thin and arched eyebrows, and the essential red lips (Fig. 41). As was common at the time, Mallo “applied” almost no makeup on the eyes.[37] The same style of eyebrows and the same red lips are also visible in Argentina (1952), Head of Black Woman (1946), Gold (1951), Young Black Woman (1948), and The Human Deer (1948). Further, red lips are overdrawn in these works, following the trend of the “Hunter’s Bow lip,” a style coined by Max Factor in the 1930s which created the illusion that the upper and low lips were the same size.[38] (Fig. 42) Argentina, painted in 1952, features a makeup style (specifically eye lining) that corresponds to the 1950s trend that emphasized the eyes and disregarded rouge.[39] By contrast, the lips of the women featured in Head of Blonde Woman/ The [Male] Champion (1951) and Sketch for Head of Woman (1940-44) are naturally-colored rather than intense red. The lack of red lipstick may be due to several factors. In the former work, Mallo may indeed have conceived of the subject as a man, as suggested by the title El campéon [The Male Champion], which was used when the work was reproduced in Para Ti (it is unknown when or why critics and scholars began to refer to the work’s subject as a woman). In the case of the latter work, which still maintains the word “Estudio” [Sketch/Preparatory drawing] in its title, Mallo might not have intended it to be a finished painting or might have chosen to present this woman in a more natural and less glamourized way, even if she slightly colored her cheeks with pinkish blush as in Head of Woman (1941). In Polynesia (1951), it is difficult to decipher the pair of works’ coloring as the only images available are photographs with insufficient color quality.

Apart from the use of color, dramatic lighting was essential to the artist’s way of sculpting the women’s faces. As opposed to natural light, which generally is more diffuse, studio lighting tended to be more theatrical. In each of the Heads of Women, the lighting scheme is different, which serves as further evidence that Mallo used models to produce these paintings, or at least based them on photographs taken in a studio since the faces match common lighting styles used in studio photography (see figure 43). For instance, the figure in Head of Black Woman (front, 1946) features a combination of lights and shadows that corresponds to the use of one light source positioned high at one side of the model. This lighting scheme creates the kind of light triangle visible on the woman’s cheek.

Hair, too, was a means for Mallo to shape viewer perceptions about beauty, and to advance conceptions of beauty and race. As for the women’s hairstyles, Head of Woman (1941) features the traditional glamorous 1940s hairstyle consisting of rolls at the front and another twist at the back (Fig. 44). Argentina, painted already in the 1950s, presents shorter hair reminiscent of the era’s popular poodle cuts or Italian cuts.[40] The woman in Sketch for Head of Woman has hair styled in braids. Black and mixed-race women painted in Head of Black Woman (1946), The Human Deer (1948), Young Black Woman (1948), and Polynesia (1951), keep their natural curls and wear their hair in afros, instead of having their hair straightened, as Black women in mass media commonly had to do during the first half of the 20th century in order to meet white standards of beauty.[41] In the Golden Age of Hollywood, movies started to present some Black stars, such as Eartha Kitt, Anne Cole Lowe, and Theresa Harris, as beautiful (Fig. 45), but this development only slightly counteracted the constant dissemination of caricaturized and disparaging images of Black women spread during the 19th and 20th centuries in all kinds of media.[42] This is because, as noted by Maxine L. Craig, “[Hollywood films] linked black beauty with dangerous sensuality and showcased as beauties only those black women who had light tan skin, wavy hair, and thin lips.”[43]

According to Julia Ariza, the growth of the number of illustrated publications targeted to women in Argentina at the beginning of the 20th century contributed to the association of whiteness with female beauty and refinement to detriment of Black and Indigenous women. Portraits of glamorous white women were powerful unto themselves, but also because they occupied a privileged position within the text and graphic layouts.[44] In figure 42, we can see a lipstick advertisement that includes multiple photos of white women. However, Ariza noted that mixed-race women, even if they were pictured in magazines, were never presented as “models of desirable beauty.” On the contrary, they were associated with a supposedly invariable Argentinean rural countryside opposed to the cosmopolitanism of urban life. [45] As she writes, “at the moment in which Josephine Baker rose as the stellar figure of modern spectacle (a role that Argentinean magazines did not hesitate in awarding her since she visited Buenos Aires) the only role that those same magazines offered to black Argentinean women was the rest of a past that was meant to soon disappear.”[46]

In her Heads featuring Black women, Mallo embraced those qualities that would later characterize the “Black is Beautiful” movement: dark skin, tightly curled hair, and full lips.[47] In presenting these subjects as glamourous on their own terms, rather than with their hair straightened, light skin, and small lips in keeping with white standards of beauty, Mallo suggested that all women were equally beautiful. They all look aristocratic, sculptural, and timeless due to the geometries that undergird them—not because their looks have been “whitened” in any way.

Figure 32. Left: Maruja Mallo. Estampa cinemática [Cinematic Print, 1927]. Ink and color pencils on paper, 44 x 31 cm. Right: Maruja Mallo. Cover for Xabier Abril’s Hollywood (Madrid: Editorial Ulises, 1931).

Figure 33. Actress Kay Francis featured on the cover of Cinelandia (July 1940)

Figure 34. Actress María Félix (1914-2002) featured in the cover of the Argentinean magazine Sintonía in 1949.

Figure 35. Reproductions of Maruja Mallo’s El Campeón (currently known as Blonde Woman, 1951) and The Human Deer (front, 1948) in the Argentinean magazine Para Ti.

Figure 36. Various covers of the Argentinean magazine Para Ti illustrated by Raúl Manteola, 1940. Compiled by Ricardo Güiraldes for Chilean Charm.

Figure 37. Maruja Mallo posing next to Head of Black Woman, profile (1946) at her exhibition “Les peintures de Maruja Mallo” at Silvagni Gallery in Paris (March 3-31, 1950).

Figure 38. Left: Maruja Mallo. Head of Woman, front, 1941. Center: Actress Vivien Leigh as Scarlett O’Hara in the movie Gone with the Wind. Right: Maruja Mallo, Argentina, 1952.

Figure 39. Maruja Mallo at the Spanish TV program A fondo in 1980, when she was interviewed by Joaquín Soler Serrano.

Figure 40. Maruja Mallo. Portrait of a Man with Color Scale, undated. Oil and pencil on cardboard, 37 x 52.5 cm. Archivo Maruja Mallo. Galería Guillermo de Osma. © Maruja Mallo

Figure 41. A vintage Maybelline ad from 1940.

Figure 42. “A New Rainbow of Lipsticks Reds…” 1940s Max Factor advertisement.

Figure 43. Comparison of Maruja Mallo’s The Human Deer (profile, 1948), Head of Black Woman (1946), and Head of Woman (front, 1941) and three different studio lighting styles of The Lighting Guide developed by The Camera World.

Figure 44. Top Hollywood hairstyles in 1941.

Figure 45. From left to right: Actresses Eartha Kitt, Anne Cole Lowe, and Theresa Harris photographed during the Golden Age of Hollywood.

[1] They also share sculpted ample jaws. The angular way in which Mallo painted some of the women’s ample jaws is an aspect that other scholars have seen as proof of Mallo’s interest in androgyny. For instance, Shirley Mangini suggests that the women of the Heads of Women series look even more androgynous than the women shown in the artist’s previous series: The Religion of the Work. Mangini, “From the Atlantic to the Pacific,” 94.

Such characteristics are not equally evident in all of them, however. For example, within the Heads series, Gold (1951) and Blonde Woman/ The[Male]Champion (1951) are characterized by androgynous faces. However, in the case of the rest of the Heads, even if some lighting effects and the sculpted facial contours may give them a certain androgynous look, the attention given to their very elaborated hairstyles, marked eyebrows and intense red lips need to be understood in the context of a culture invested in defining female beauty.

[2] Related to cinema. “Cineástica” was a term invented by Ramón Gómez de la Serna, whose own literary practice is characterized by the inclusion of poetical neologisms.

[3] Gómez de la Serna, Maruja Mallo, 10.

[4] These include the series of Estampas cinemáticas (1927-1928), Charlot (1929), Harold en la verbena (1930), and a series that she began to make but never published titled Le cinéma comique.

[5] Judith Nantell, “Cinematic Art, Maruja Mallo and Modern Visual Culture,” Journal of Spanish Cultural Studies 12, no. 4 (December 2011): 464. In this excerpt, she is quoting from Francesco Casetti. Eye of the Century. Film, Experience, Modernity, translated by Erin Larkin with Jennifer Pranolo (New York: Columbia UP, 2005/2008): 8.

[6] Maruja Mallo, “Posición,” Hombre de América, no. 21 (August, 1943): 2. This number of Hombre de América had Mallo’s Mensaje del Mar featured in its cover.

[7] My translation. Original text in Spanish: “A una humanidad nueva corresponde un arte nuevo. Porque una revolución artística no se contenta solamente de hallazgos técnicos. El verdadero sentido que hace un arte nuevo e integral, es, además de un conocimiento sólido y de un oficio manual seguro, la aportación de una iconografía, para una religión viva, para un nuevo orden.” Mallo, “Posición,” 2.

[8] Maruja Mallo, ‘‘Cinema y arte nuevo: originalidad de Maruja Mallo,’’ interview by Luis Gómez Mesa, Popular Film no. 198 (1930), 3. Quoted in Nantell, “Cinematic Art,” 1.

[9] Julia Ariza, “Imagen impresa e historia de las mujeres: representaciones femeninas en la prensa periódica ilustrada de Buenos Aires a comienzos del Siglo XX (1910-1930)” (PhD diss., Universidad de Buenos Aires, 2017), 34.

[10] Matthew B. Karush, Culture of Class: Radio and Cinema in the Making of a Divided Argentina, 1920-1946 (Durham & London: Duke University Press, 2012), 81.

[11] Karush, Culture of Class, 82.

[12] Matthew B. Karush. “Populism, Melodrama, and the Market: The Mass Cultural Origins of Peronism,” in The New Cultural History of Peronism: Power and Identity in Mid-Twentieth-Century Argentina, edited by Matthew Karush (Durham: Duke University Press Books, 2012): 28-29.

[13] Jennifer H. Miller, “Casting Race: A History of Makeup Technology in the U.S. Film Industry, 1890-1940” (PhD diss., University of Rochester, NY, 1998): iv.

[14] Mary Desjardins, “Classical Hollywood, 1928–1946,” in Costume, Makeup, and Hair, edited by Adrienne L. McLean (Rutgers University Press, 2016), 48.

[15] Desjardins, “Classical Hollywood,” 69-70.

[16] Desjardins, “Classical Hollywood,” 69-70.

[17] Sintonía was launched in 1933 by Haynes publishing house. Radiolandia adopted this name in 1934. Julio Korn, editor and owner, decided to change it from the previous title La Canción Moderna. Antena, which appeared in 1931, was also owned by Korn since 1937. María Florencia Calzón Flores, “Radiolandia en los cuarenta y cincuenta: una propuesta de entretenimiento,” XII Jornadas Interescuelas/Departamentos de Historia. Departamento de Historia, Facultad de Humanidades y Centro Regional Universitario Bariloche. Universidad Nacional del Comahue, San Carlos de Bariloche (2009), 2.

[18] Julia Ariza notes that the cultural changes of the 1930s precisely propitiated the disappearance of some illustrated magazines from 1910-1930 and the appearance of these other feminine magazines like the one that we have mentioned. Ariza, “Imagen impresa,” 34.

[19] In several newspapers of the time, it was common to see announcements of parties in honor of Mallo organized by the director of the magazine Lyra, Francisco Ecli Negrini. In “En honor de Maruja Mallo,” El Hogar. Buenos Aires (February 4, 1949) a photo shows Mallo with Francisco Ecli Negrini on the occasion of the party that he organized to celebrate her success in New York.

[20] In Buenos Aires, Spanish refugees created the publishing houses Sudamérica and Emecé. In 1938, Gonzalo Losada Benítez, who worked for the Argentinean branch of the Spanish house Espasa Calpe, decided to found Losada. Dora Schwarzstein, El exilio español en la Argentina (Alicante: Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes, 2017), 6-7.

[21] For Lyra, Mallo designed the cover of number 31-32, using the technique of collage and, for El Hogar, she drew Estampas de 1900 (August1938). Carmen Gaitán Salinas and Idoia Murga Castro, “Victorina Durán y Maruja Mallo: encuentros y desencuentros de dos artistas exiliadas,” Arenal 26, no. 2 (July-December, 2019): 412.

The first monograph on the artist, published in 1942 by Losada was reviewed in El Hogar, no. 1763 (July 30, 1943) and in Argentina Gráfica, no. 84 (June 1943). As she often visited Uruguay, her work was also discussed in Uruguayan magazines: “El Arte Humano de Maruja Mallo,” Mentor: Revista Uruguaya Ilustrada (October 1939).

Mallo also had a special connection with Atlántida Publishing House, one of the most important of Argentina and producer of titles like the homonymous magazine Atlántida (1918), the weekly sports magazine El Gráfico (1919), the children’s magazine Billiken (1919), and Para Ti (1922), considered the first “women’s magazine” in the country. According to Idoia Murga, for Atlántida, Mallo at least designed three drawings and she likely made some for Billiken too. Those were Buenos Aires 1830 (July, 1937), Un soldado de Urquiza (November, 1937) and Papá Noel (January, 1938). Gaitán and Murga, “Victorina Durán and Maruja Mallo,” 413.

[22] My translation. Original text in Spanish: “La que aquí presentamos es la última obra de la genial pintora española Maruja Mallo, residente en Buenos Aires (…) Su impresionante colorido, la magia del claroscuro, la sobriedad de la expresión, la belleza y la gracia que dominan en todos los detalles culminan en esta obra hasta alcanzar la difícil y admirada perfección.” This text is the caption that accompanies the reproduction of Argentina (1952) in a separate page of magazine Para Ti that it is preserved as part of of Maruja Mallo’s Archive.

[23] Following similar aesthetics Meléndez also mentions the covers of Maribel, El Hogar and Atlántida. Amelia Meléndez Taboa, “Maruja Mallo entre artistas mujeres y arte femenino.” VIII Jornadas Nacionales de Historia de las Mujeres. III Congreso Iberoamericano de Estudios de Género, Córdoba, Argentina (25-28 October 2006), 7.

[24] Gisela Paola Kaczan, “Estampas del deseo y del desear. Imágenes de moda en Argentina en las primeras décadas de 1900,” Cadernos Pagu, no.41 (July-December, 2013): 146-147.

[25] “The Production Code,” in Movies and Mass Culture, edited by John Belton (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1996), 140.

[26] Mary Ann Doane, “The Close-Up: Scale and Detail in the Cinema,” Differences 14, no. 3 (2003), 92.

[27] Mangini, Maruja Mallo, 168.

[28] González Cubero, “Photographs of the Theatre,” 208.

[29] “Lyra agasaja a descollantes figuras del círculo artístico internacional en ocasión de su despedida,” Lyra no.26, Buenos Aires, October, 1945. Press clipping, Archivo Maruja Mallo.

Mallo also noted when she thought a woman posed a particularly remarkable beauty, as in the case of Delia del Carril (wife of Pablo Neruda) and her sister Adelina del Carril, who she respectively labeled “muy bonita” (very beautiful) and “prodigiosa” (prodigious). Maruja Mallo. “Maruja Mallo-A fondo,” interview by Joaquín Soler Serrano (April 14, 1980) Video, RTVE Archive, 40:45-41:05/56 min.

[30] Mallo enjoyed using layered colorful clothes with different prints, especially floral motifs. In the seventies and eighties, it was also common to see her wearing her iconic fur coat. To know more on how Mallo constructed her artistic persona through the use of photographs see Patricia Mayayo, “Maruja Mallo: el retrato fotográfico y la ‘invención de sí’ en la vanguardia española,” MODOS revista de história da arte 1, no. 1 (January-April, 2017): 71-88. To read about the artist as a bohemian see Shirley Mangini, “Maruja Mallo. La Bohemia encarnada,” Arenal 14, no. 2 (July-December 2007): 291-305.

[31] Mayayo, “Maruja Mallo: el retrato fotográfico,” 72.

[32] María Escribano, “Maruja Mallo, una bruja moderna,” in Maruja Mallo (Buenos Aires: Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes de Buenos Aires/Consellería de Cultura. Xunta de Galicia, 1994), 45.

[33] Maruja Mallo, “Imágenes. Artes visuales: Maruja Mallo,” min. 41:01- 41:55 of 54:28.

[34] Miller, “Casting Race,” 10-11.

[35] Max Factor played a prominent role in the field of fashion and cinema as contributed to the creation of makeup, different kinds of lamps, and three-color Technicolor and Eastman color. Miller, “Casting Race,” 193.

[36] Miller, “Casting Race,” 193-194.

[37] Read more details on the 1940s typical facial look in Louise Young and Loulia Sheppard, Timeless: A Century of Iconic Looks (London: Mitchell Beazley, 2017): 72-74.

[38] Madeleine Marsh, Compacts and Cosmetics: Beauty from Victorian Times to the Present Day (South Yorkshire: Pen & Sword Books, 2009): 88.

[39] Richard Corson. Fashions in Makeup: From Ancient to Modern Times. London: Owen, 1972), 533.

[40] Victoria Sherrow, Encyclopedia of Hair: A Cultural History (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2006), 192.

[41] Maxine Leeds Craig, “Black Women and Beauty Culture in 20th-Century America,” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History (November 20, 2017): n.p.

[42] Craig, “Black Women,” n.p.

[43] Craig, “Black Women,” n.p.

[44] Ariza, “Imagen impresa,” 72.

[45] Ariza, “Imagen impresa,” 199.

[46] My translation. Original text in Spanish: “En efecto, en el momento en que Josephine Baker ascendía como figura estelar del espectáculo moderno (un lugar que las propias revistas argentinas no vacilaron en otorgarle a raíz de su visita a Buenos Aires) el único papel que esas mismas revistas ofrecían a las mujeres negras argentinas era el de restos de un pasado en vías de desaparición.” Ariza, “Imagen impresa,” 193.

[47] Craig, “Black Women,” n.p.

Web design: Esther Rodríguez Cámara, 2021

![Maruja Mallo. "Blonde Woman" or "The [Male] Champion," 1951.](https://edspace.american.edu/marujamalloheadsofwomen/wp-content/uploads/sites/1773/2021/02/mujer-rubia_1951_marujamallo.jpg)