HOME › PART 2: Painting for Equality › A Controversial Title

A Controversial Title:

The “Supremacy of Races,” or “Heads of Women”?

“Buscaba nada más la supremacía de las razas, que tenían todas las razas derecho a vivir y que habían quedado vencidas, pues, por los sometimientos de las armas. Porque en América yo creo que el sometimiento fue por la cruz y la pólvora.”

While Maruja Mallo lived in exile (1937-1965) and, in fact, throughout the 20th century, the issue of race was central to Latin-American politics. Most of the debates took place in the context of governments interested in defining national identity and establishing the role of their nation’s Indigenous and Black populations in it. Other conversations, that of course had resonance on a political level, were happening in the ethnographic and literary fields. A growing number of ethnographers, sociologists, and intellectuals proposed racial and ethnic diversity as the intrinsic power of Latin America in an effort to fight national internal fragmentation (in not unproblematic ways), White supremacy, and even Darwinist ideas. However, motivations and approaches to the same issues varied, as noted by Eduardo Elena:

Typically, mid-century nationalist reforms were not framed explicitly as programs for racial uplift; their advocates preferred, instead, to emphasize ideals of modernization, social peace, and collective justice. Nevertheless, these movements promised, and in some cases delivered, improvements demanded by laboring majorities that included racially stigmatized sectors. At the same time, many of these movements embraced, to various degrees and with varying motivations, cultural nationalisms that valorized African and/or indigenous folkways and acknowledged the virtues of multiracialism and mestizaje.[1]

Some countries denied that racism was a problem for them, arguing that the degree of segregation and violence within their territories never reached the levels seen in the United States or South Africa, that the only true criteria for a society’s hierarchization was class, or that their populations were just “mixed.”[2] Furthermore, the question of the role of Black people within a nation began to be considered first only in countries like Brazil and Cuba with larger black populations and then in the rest of the region.[3] For instance, from the 1930s the notion of “racial democracy” became particularly influential in Brazil (and later in other countries) through the work of sociologist and anthropologist Gilberto Freyre (1900-1987). Compared to the US, he perceived that, in Brazil, there has been less segregation. Therefore, he considered the latter to be a “racial democracy” because, in his view, it represented an example of a tolerant mixed society.[4] According to Peter Wade, the idea of Brazil as a “racial democracy” set the agenda for much of the study of Blacks in Latin America generally,[5] but racism continued to be strong, because “the existence of a large, even majority mixed-race population is no barrier to the persistence of racism against certain categories of people and also within the mestizo majority itself.”[6] By contrast, Argentina was one of those countries that focused on ideas of class and saw itself as a predominantly White country.[7] According to Eduardo Elena, this generalized attitude has prompted historians to view Argentina as a regional outlier within these debates on the theme of race.[8]

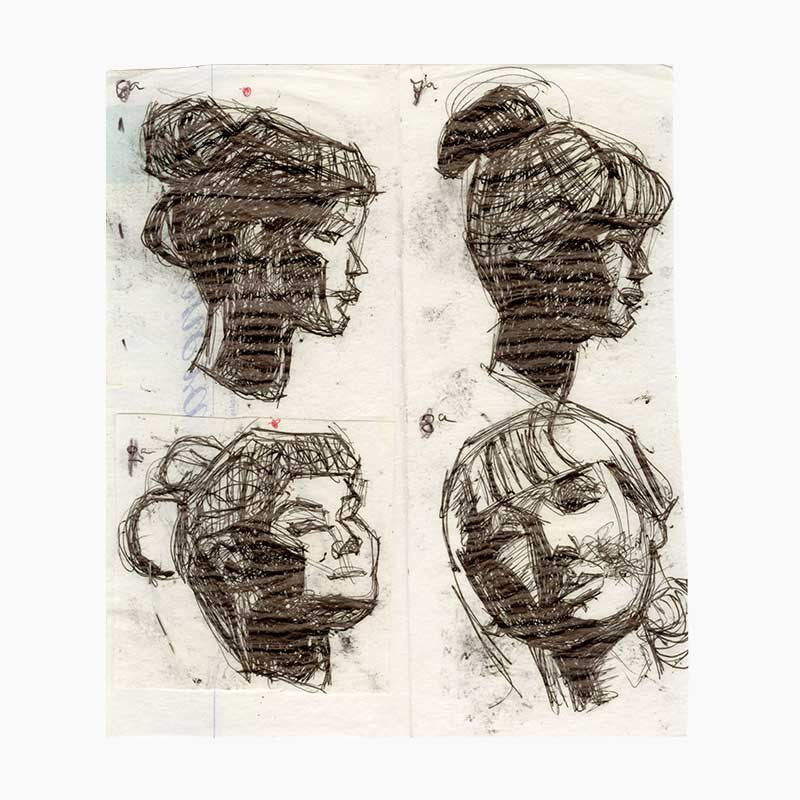

Clearly, Mallo was sensitive to these tensions and deeply reflected on them in her series of Heads. Interestingly, the series’s title offers one of the first clues about her interest in race. In the 1979’s interview cited earlier, she noted that among the works purchased by jeweler Samuel Mallah: “there was a series of heads that I titled The Supremacy of the Races” (La supremacía de las razas, in Spanish).[9] When and why the title was changed to Heads of Women remains unclear, but it is evident that this more neutral title skirts charges that Mallo was vested in racial “supremacy.” As “supremacy” means the condition of being superior to others, such a word implies a hierarchy that is subsequently annulled by the use of the plural of “races.” If all races enjoy “supremacy,” is this not the same as saying that they are all equal? Therefore, the original title of the series was likely later eliminated to prevent any association of the series with ideas of “White supremacy,” which is the concept with which this term is currently associated. Paradoxically, what Mallo wanted to demonstrate with these paintings was her position against White supremacy, which still dominated social and political discourses both in Spain and Latin America in the 1940s, when she started work on the Heads. In the same interview with Spanish public television, Mallo declared that her motivation for the Heads of Women series was as follows:

I was only searching for the supremacy of the races, [to show] that all races have the right to live and that they have been defeated by the submission caused by weapons. Because I believe that in [Latin] America the subjugation was due to the cross and the gunpowder.[10]

Here, again, Mallo employed the word “supremacy” as a sort of paradoxical synonym of “equality.” Furthermore, in her first phrase, she is clearly thinking of “all” races, while in the second she is referring to only those who suffered the consequences of colonial rule in Latin America. This was later clarified by metaphorically alluding to the role of the Church (the cross) and Spanish conquers (the gunpowder) as the origin of race inequalities on that continent. This is an important statement, as it situates Mallo’s disenchantment with Spain’s colonial past as the driving force that led to her Heads of Women and enables us to see the series as her refusal of it.

In the 20th century in Spain, as opposed to countries like Brazil, race was not explicitly considered to be a central issue in the construction of national identity, which was understood to be rooted in other markers. For instance, Catholicism had played a prominent role in the construction of a unitary Spanish identity since the sixteenth century.[11] Despite this, in the 1920s, some texts written in Spain acknowledged and reified ideas of race, as can be seen in this example from the eugenicist Luis Huerta:

Each race contributes to the history of civilization with the particularities of their mental characteristics. In this way, broadly speaking, the Caucasian race is the sovereign due to the zenith of their ethnical and aesthetical order; the yellow stands out because of its intellectual liveliness; the black manifests its vigor and somatic resistance; the red amazes us because of its serenity and presence of mind.[12] (emphasis my own)

In the Hispanic world there were also still voices who saw miscegenation as a threat against the perceived purity of the Spanish race, as exemplified by the tract “Significado de la Conquista” [Meaning of the Conquest] by Enrique Martínez Paz, which was published in 1944 by the National Academy of History of Argentina:

As in all conquest, the culture of those defeated filtered its poisonous influence in order to dissolve the specific personality of the victors (…) The gravest obstacle for the establishment of the Spanish culture in America was the crossing of races.[13]

In Spain, “the concept of the nation was dependent on what was understood as the overseas (the “colonial”),” As noted by Richard Cleminson.[14] This notion prevailed into the 1940s and the dictatorship of Francisco Franco (1939-1975). Although Mallo did not live in Spain from 1937 to 1965, these ideas had echoes in Latin America. As an example, we can cite the “Day of the Race” (Fiesta de la Raza), a national holiday celebrated in Spain since 1892 that takes place on the 12th of October. As noted by María del Mar del Pozo and Jacques F.A. Braster, “this day was highly valued by the Catholic Church, that interpreted the discovery of America as the start of the successful ‘Christianization’ of the new continent.”[15] Interestingly, since the 1910s and 1920s, Latin American countries such as Argentina, Perú, Chile, and Cuba subscribed to the celebration as a way to oppose the growing influence of the United States in their territories.[16] During the first half of the 20th century, unrecognized privilege among the Spanish, and an appreciable degree of paternalism on Spain’s part towards the Latin American population, were palpable.

These were the kinds of outdated but still pervasive beliefs that Mallo surely wanted to combat when she declared in 1979 that her Heads were meant to show the equality of those races that had been defeated by “the cross and the gunpowder.”[17] She seemed to understand the violent legacy of colonialism in Latin America as one of the reasons why people of color were still subjugated. By means of painting this series, she was contesting hierarchies inherited from the past that were still very vivid during the middle of the 20th century.

According to Zanetta, in Mallo’s series The Religion of Work, the artist transformed the drawings of fishermen that she did while experiencing the horrors of the Spanish Civil War into universal archetypes symbolizing a new religion “based on tolerance and in harmony, the religion of the ‘Universal Mankind.’”[18] I propose that in Heads of Women the artist continued her commentary against everything that implied destruction and repression. Instead of responding to the reality of the war in her native country, she introduced her beautiful multi-racial archetypes as a reaction against the submission caused by colonial powers of the past against Indigenous and Black communities in Latin America.

[1] Eduardo Elena, “Argentina in Black and White: Race, Peronism, and the Color of Politics, 1940s to the present,” in Rethinking Race in Modern Argentina, edited by Paulina Alberto and Eduardo Elena (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016), 184.

[2] Peter Wade, “The Political Economy of Race and Sex in Contemporary Latin America.” In Race and Sex in Latin America, 156-207 (London: Pluto Press, 2009): 157.

[3] Wade, Race and Ethnicity, 50

[4] Wade, Race and Ethnicity, 51.

[5] Wade, Race and Ethnicity, 52.

[6] Wade, “The Political Economy of Race,” 157.

[7] Argentinean 19th-century elites built the nation upon the concept of Whiteness and in relation to its European origins. Read more on the relevance of race in the process of nation-building in Argentina in Ezequiel Adamovsky, “El color de la nación argentina. Conflictos y negociaciones por la definición de un ethnos nacional, de la crisis al Bicentenario,” Jahrbuch für Geschichte Lateinamerikas 49 (2012): 343-364.

[8] Elena, “Argentina in Black and White,” 185.

[9] “Entonces no he podido hacer todas las fotografías que hubiera deseado de todos mis cuadros, que los compró casi todos un israelita francés que se llamaba Samuel Mallah que tenía una joyería en París, otra en Nueva York, otra en Chile y otra en Argentina…. Y tenía la joyería mezclada con los cuadros, porque tenía los cuadros como joyas. Y él se quedó con casi todas… Pues me compró como treinta y tantas cabezas, donde figuran una serie de cabezas que yo titulaba La supremacía de las razas.” Maruja Mallo, “Imágenes. Artes visuales: Maruja Mallo,” min. 38:58 of 54:28.

[10] My translation. Original in Spanish: “Buscaba nada más la supremacía de las razas, que tenían todas las razas derecho a vivir y que habían quedado vencidas pues por los sometimientos de las armas. Porque en América yo creo que el sometimiento fue por la cruz y la pólvora.” Maruja Mallo, “Imágenes. Artes visuales: Maruja Mallo,” min 39:57 of 54:28.

[11] Pablo Alonso González, “Race and Ethnicity in the Construction of the Nation in Spain: the Case of the Maragatos,” Ethnic and Racial Studies 39, no. 4 (2016): 616.

[12] My translation. Original text in Spanish: “Cada raza aporta a la historia de la civilización los peculiares influjos que constituyen su característica mental. Así, y a grandes rasgos, la raza caucásica, lleva la soberanía por sus culminaciones de orden étnico y estético: la amarilla destaca por su vivacidad intelectual: la negra manifiesta su vigor y resistencia somática; la roja asombra por su gran serenidad y presencia de ánimo.” Luis Huerta, “La genicultura,” Eugenia, no.33 (1923): 378. Quoted in Francisca Juárez González, “La eugenesia en España, entre la ciencia y la doctrina sociopolítica,” Asclepio 51, no.2 (1999): 122.

[13] My translation. Original text in Spanish: “Como en toda conquista, la cultura de los vencidos filtraba su venenosa influencia para disolver la personalidad específica de las instituciones de los vencedores (…) El más grave obstáculo para la implantación de la cultura de España en América, fue la cruza de razas.” Enrique Martínez Paz, “Significado de la Conquista,” Boletín de la Academia Nacional de la Historia 17 (Buenos Aires 1944): 168.

[14] Richard Cleminson, “Iberian eugenics? Cross-overs and contrasts between Spanish and Portuguese eugenics,” Dynamis 37, no. 1 (2017): 101.

[15] María del Mar del Pozo Andrés and Jacques F.A. Braster, “The Rebirth of the ‘Spanish Race’: The State, Nationalism, and Education in Spain, 1875–1931,” European History Quarterly 29, no. 1 (January 1999): 85.

[16] Del Pozo and Braster, “The Rebirth of the ‘Spanish Race,’” 85.

[17] Maruja Mallo. “Imágenes. Artes visuales: Maruja Mallo,” 40:32 of 54:28 min.

[18] María Alejandra Zanetta, “Continuación de su compromiso social en el exilio: La Religión del Trabajo,” section 6 in La subversion enmascarada. Análisis de la obra de Maruja Mallo (Madrid: Biblioteca Nueva, 2014): Kindle, n.p.

Web design: Esther Rodríguez Cámara, 2021