HOME › PART 2: Painting for Equality › Revising Brazilian Depictions of Mixed-Race Women

Revising Brazilian Depictions of Mixed-Race Women

In Brazil, the first decades of the twentieth century brought accelerated industrialization, the urbanization of Sao Paulo, and the growth of the middle class and urban proletariats.[1] According to Carine da Costa Cadilho, this atmosphere served as fertile ground for the development of modernism in the arts, especially by those artists and intellectuals who had the means to travel and study in Europe for some time. These artists were attracted to everything that represented Brazilian “national roots,” including its people, colors and landscapes. They depicted Black and mixed-race people as a positive representation of brasilidade, but still associated these communities with labor, poverty, and/or sensuality.[2]

Mallo was aware of this tradition, for she knew the work of these painters and was familiar with the Brazilian art world, which was especially connected with that of Argentina, especially from the 1940s onwards. According to Rodrigo Gutiérrez, this cultural exchange was due to Brazilian intellectuals who spread the work of Brazilian artists in Argentinean journals, to Argentinean painters’ visits to Brazil, and their participation in the São Paulo Biennale (which led to the inclusion of Brazilian themes in their work), and to the role of Alfredo Bonino’s galleries, who moved artworks from his Buenos Aires headquarters to Rio de Janeiro and New York.[3] In fact, Maruja Mallo exhibited eight of her Heads at Bonino Gallery in Buenos Aires in 1971. We also know that she was particularly aware of what happened at the Biennial of São Paulo of 1951 because she commented on it in a letter to her friend Jorge Oteiza.[4]

Mallo was not only personally struck by the diversity of people she encountered in Latin America, but, in Brazil, she saw precedent for ways to include and address this diversity in art. Black and mixed-race women were presented in Brazilian modernist painting as central protagonists in Brazil’s history and society instead of marginalized to a peripheral place. However, in many cases, painters also connected the women with primitiveness and sensuality, in a way that tended to debase them.

Tropical (1917) by Anitta Malfatti (1889-1964) is usually regarded as one of the first modern-art Brazilian works centered on the figure of the mixed-race woman (Fig.57). It depicts a woman carrying a basket full of tropical fruits against a stereotypical background of banana and palm trees. According to Marcos César de Senna Hill, Malfatti presented this mixed-race woman as a servile street vendor and contraposed her melancholic attitude with a lowcut neckline that echoed Brazilian female clothing of the beginning of the 19th century, such as that visible in Jean-Baptiste Debret’s lithographies Escravas de diferentes Nações.[5]

With her iconic A negra (1923), Tarsila do Amaral (1886-1973) also tried to add elements of brasilidade to her painting but, as Hill points out, “the painter ended up activating an already existing iconographical field related to a well-established anthropological background.”[6] Indeed, this painting was intended to assert the figure’s status as a nanny or servant, and Kanitra Fletcher reminds us that the use of mask-like features and the contrast between the voluptuousness of the woman’s body and the modernity of her angular background ends up “point[ing] toward a view of the black female figure as masked/invisible, naked/powerless and unclothed/uncivilized.”[7] (Fig. 58)

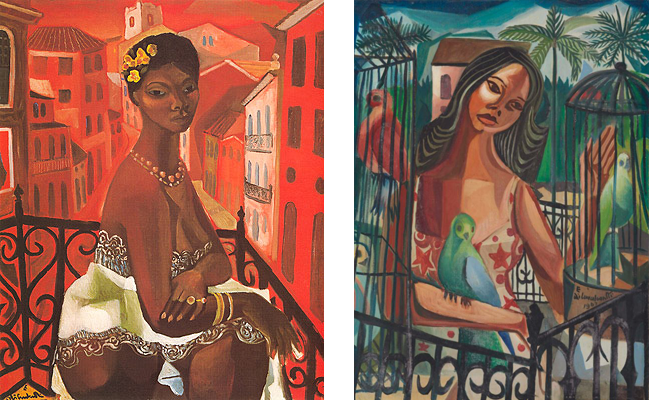

For his part, Emiliano di Cavalcanti (1897-1976) was particularly well known for his numerous portraits of mixed-race women and for a life-long obsession with the female body. In most of the portraits, the painter emphasized the sensuality of the women he portrayed through ample necklines, as in Abigail (1940), or exposed breasts in a way profoundly influenced by ideas of the hypersexual Black woman that proliferated during eras of slavery, as in Samba (1925) or Mulatas (1927).[8] (Fig. 59) In paintings like Mulata em Rua Vermelha (1960) women were placed in an urban or brothel-like setting, while in others, like Mulata e pássaros (1967) the painter associated Black women with the fecundity of nature and surrounded them with leaves, flowers and/or birds (Fig.60). Mallo first met Di Cavalcanti at the beach while she was staying at the Copacabana Palace in Rio de Janeiro.[9] Although we cannot be certain, she might have visited his studio, too, where he painted from real models that have been identified, unlike those who Mallo painted, whose names remain unknown. Around the time Mallo was in Brazil, Di Cavalcanti’s preferred mixed-race model was Zulia. From the 1960s on, he instead focused on model and actress Marina Montini.

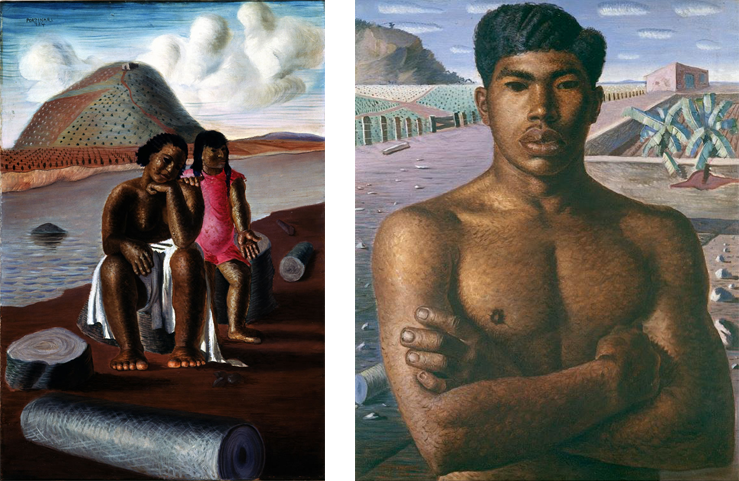

Mallo was also aware of the work of the celebrated Cándido Portinari (1903-1962), who throughout his career focused on painting images of the production of coffee, cacao, and sugar in the Brazilian countryside. When she visited the Ministerio da Educação e Saude Pública in Rio de Janeiro in 1946 Mallo very likely saw his murals, because she then commented to the press that Portinari had been a good choice for the commission of the building decoration.[10] Portinari also placed mixed-race and Indigenous men and women at the center of his work. For example, Carine da Costa argues that in Índia e Mulata (1934) the mixed-race and Indigenous women featured in the painting are the product of miscegenation with white Brazilians, represented by the expansive landscape around them.[11] (Fig. 61)

Departing from her predecessors and contemporaries, Mallo did not depict Brazilian mixed-race women as objects of sexual desire or in the form of conventional stereotypes. Instead of including sensuous necklines and jewelry and emphasizing her subjects’ voluptuousness, she focused exclusively on their heads. She may have intended, with this decision, to subvert the Surrealist male trend of reducing women to erotic body parts or headless bodies, as proposed by Alejandra Zanetta.[12] This author proposed that Mallo chose to depict only the women’s heads in order to highlight the cerebral part of the female sex that had been ignored by men.[13] Indeed, reducing her canvases to a powerful face avoids the most common sexual connotations associated with other paintings of Black and mixed-race women in Brazilian painting. This decision also detached them from the rural and labor environments that had been associated with these communities. Furthermore, she did not mask her subjects or present them unclothed or as “uncivilized,” nor did she include landscapes that referenced labor as Malfatti or Portinari had. However, Mallo does connect African descendants with nature in some of the Heads, as I will discuss in the following section. This might signal that Mallo was not totally able to divest herself of the belief that these women were more “exotic” and “connected to nature” than, for example, the Caucasian one represented in Head of Woman (1941). Again, although she aspired to picture women of a variety of races and ethnicities as beautiful and equal, the biases of her time become manifest despite herself.

Figure 57. Anita Malfatti. Tropical, 1917. Oil on canvas, 77 x 102 cm. Collection of the Art Museum of Sao Paulo, Brazil.

Figure 58. Tarsila do Amaral. A Negra, 1923. Oil on canvas, 100 x 80 cm. Museo de Arte Contemporânea de Universidade de São Paulo.

Figure 59. Right: Emilio di Cavalcanti, Samba, 1925 (destroyed in 2012). Oil on canvas, 175 x 154 cm. Left: Emiliano di Cavalcanti, Mulatas, 1927. Oil on cardboard, 50 x 39 cm.

Figure 60. Right: Emiliano di Cavalcanti, Mulata em Rua Vermelha, 1960. Oil on canvas, 98 x 79 cm. Left: Emiliano di Cavalcanti, Mulata e pássaros, 1967. Oil on canvas, 81.3 x 61 cm.

Figure 61. Cándido Portinari. Índia e Mulata, 1934. Oil on canvas, 72 x 50 cm. Private Collection, Brazil. Left: Cándido Portinari. Mestiço, 1934. Oil on canvas, 65.5 x 81 cm. Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo.

[1] Cadilho, “O negro e o mestiço,” 20.

[2] Cadilho, “O negro e o mestiço,” 20.

[3] Gutiérrez Viñuelas, “Seoane en el centro,” 22.

[4] Maruja Mallo. Maruja Mallo to Jorge Oteiza, December 18, 1952. Letter. In Maruja Mallo. Orden y Creación, 63.

[5] Marcos César de Senna Hill, “Quem são os mulatos? Sua imagem na pintura modernista entre 1916 e 1934” (PhD diss., Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Escola de Belas Artes, 2008): 182-183. Jean-Baptiste Debret’s lithographies Escravas de diferentes Nações appeared in his book Viagem pitoresca e histórica ao Brasil (published in three volumnes from 1834 to 1839).

[6] Marcos César de Senna Hill, “Mulatas” e negras pintadas por brancas: questões de etnia e gênero presentes na pintura modernista brasileira (Belho Horizonte: C/Arte, 2017): 162.

[7] Kanitra Fletcher, “Damage Control: Black Women’s Visual Resistance in Brazil and Beyond” (Master’s thesis, The University of Texas at Austin, 2011), 19-20.

[8] Fletcher, “Damage Control,” 7-8.

[9] The anecdote regarding this encounter is particularly entertaining. Brazilian writer and reporter Rubem Braga recalled years later how Maruja Mallo and Di Cavalcanti met. According to him, both painters were introduced by phone, so Di Cavalcanti asked her how he was supposed to recognize her among all the bathers at the beach. To that, she answered that thanks to her bathing suit, which was white in the front and red in the back. Braga remembers that Di Cavalcanti told him how he kept repeating in his head Mallo’s phrase for weeks: “white in the front, and red in the back!” (original phrase: “blanco por delante y colorado por detrás”). Rubem Braga, “Recado de París,” Correio da Manhá, Rio de Janeiro (February 17, 1950): 2.

[10] “Ouvindo Maruja Mallo, no Rio,” O Jornal (Section “Revista”) no. 7923, Rio de Janeiro, February 24, (1946): 1.

[11] Cadilho, “O negro e o mestiço,” 66.

[12] Zanetta also recalls a famous French proverb that says “Femme sans tête tout en est bon” [All is good in a headless woman]. Zanetta, “Retratos Bidimensionales,” section 8 in La subversion enmascarada, n.p.

[13] Zanetta, “Retratos Bidimensionales,” section 8 in La subversion enmascarada.

Web design: Esther Rodríguez Cámara, 2021