About

This Project

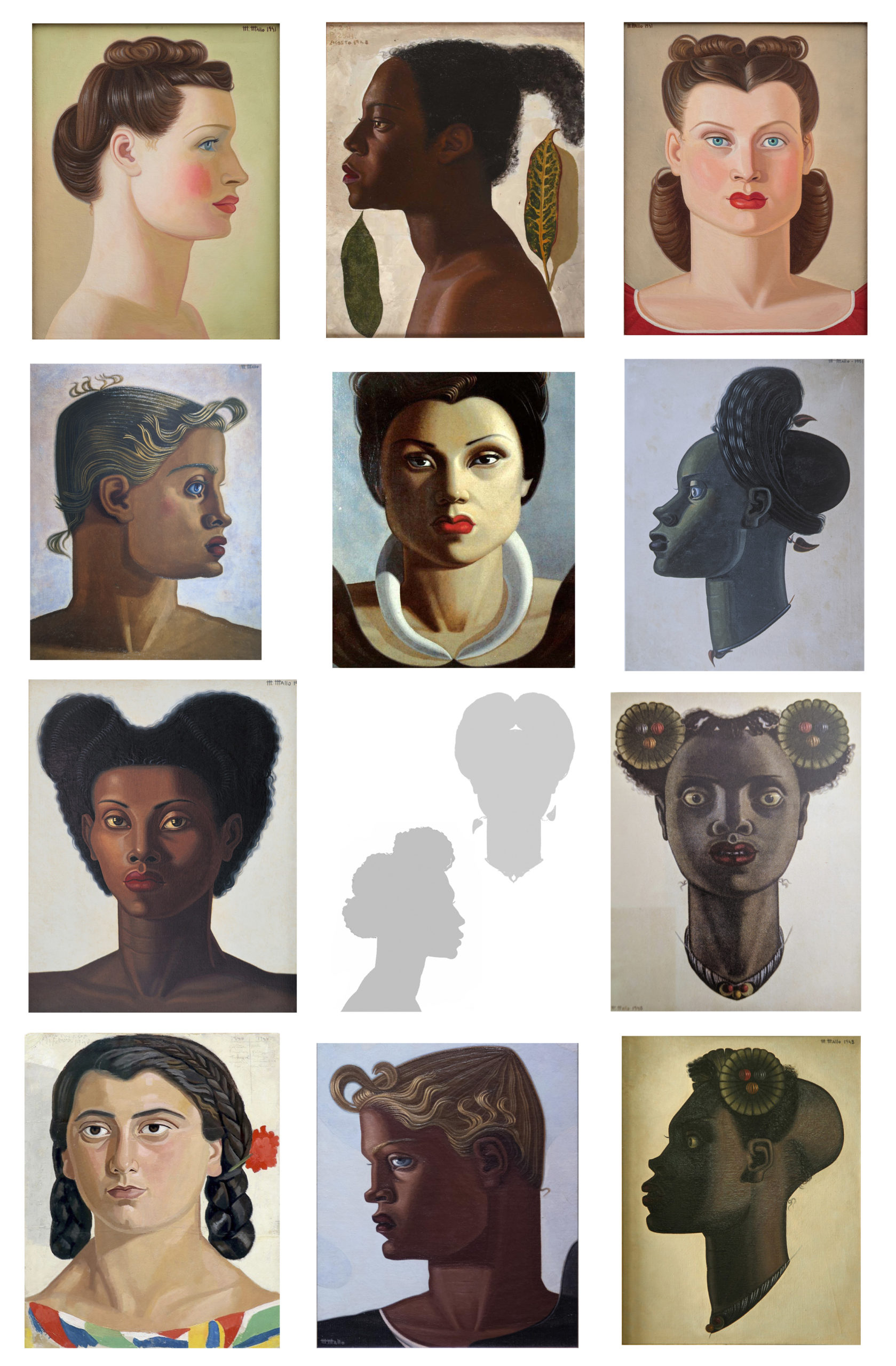

Figure 1. Maruja Mallo, Heads of Women, c. 1940-1952.

This MA capstone project is devoted to a series of paintings currently known as Cabezas de Mujer [Heads of Women] or Retratos Bidimensionales [Bi-dimensional Portraits] by the Spanish artist Maruja Mallo (1902-1995). Painted from c.1940 to 1952 while Mallo was in exile in Latin America, these paintings of multi-ethnic women’s faces presented frontally or in strict profile are some of the most exciting and lesser-studied paintings of the artist’s career (see figure 1).

I argue here that Mallo participated in contemporary political, social, and racial discussions not through writing, as did other intellectuals at the time, but rather through this series. From the 1920s through the 1950s, a growing number of novelists, anthropologists, sociologists, and politicians in most Latin-American countries explored the relationship between race and national identity in their work. The emergence of Latin American nations as post-colonial states became the frame for their theories, which tried to fight national internal fragmentation and racial inequalities. Just as those discourses revealed the instabilities of racial identity in Latin American, Mallo’s Heads present inherent contradictions too. Coming from Spain, a country that was still struggling to define its national character, Mallo attributed the discrimination of Black and Indigenous peoples to the violent legacy of colonialism in Latin America. Furthermore, since she lived mostly in Argentina, which for years dissimulated the presence of its Afro-Argentinian, Indigenous, and Asian minorities, she sought in the series to contest hierarchies inherited from the past that were still very vivid during the first decades of the 20th century.

Influenced by the many experiences that she had in Argentina, Brazil, and beyond, Mallo aspired to introduce diversity into Argentinean and Spanish portraiture. By combining her interests in geometry, art history, and popular culture, she created images of timeless beauty that challenged racist ideas about human difference and posited women of various and mixed ethnicities as equally glamorous and iconic. That said, while she intended to depict the beauty and equality of all races and ethnicities in her Heads, certain strategies she employed to make these claims betrayed entrenched understandings of Blackness and Indigeneity in Latin America at the time. For all her interest in making a statement in support of racial inclusion, her strategies ended up essentializing some of her subjects.

Despite the quality of Mallo’s art and her recognition in Spain, where she has become the local version of Frida Kahlo and an emblem of the power of women in the arts, she has not yet been incorporated into the global history of art.[1] I would suggest several reasons for this elision. First, those males counterparts who remained in Spain during her exile in Argentina from 1937 to 1965 did everything to erase her from Art History, and it was not until the end of the seventies that her work started to be rescued and valorized by artistic circles in Madrid, which mirrored the increased liberalness of the Spanish society of those days.[2] Second, after Mallo’s return to Spain, contemporaneous columnists chose to focus on her personality, her relationship to previous romantic partners, and the many anecdotes about her life rather than on her art, such that they ended up marginalizing her work. Furthermore, as she was a Spanish artist working in South America, she occupied a liminal space between both cultures. To make things more complicated, almost all of the scholarship on her is written in Spanish and only some articles have been published in prominent English-language journals or as chapters in books —but mostly in the context of Hispanic studies publications, not in art history ones.[3] Indeed, this project stands as the first virtual project devoted to an in-depth analysis of a selection of Mallo’s art, making it available to a global audience.

Figure 2. Maruja Mallo in her house-studio in Buenos Aires in 1944. Archivo Maruja Mallo.

In light of the state of the literature on Maruja Mallo, which has amply reviewed the artist’s biography and documented her entire oeuvre, it is the goal of this project to focus solely on, interpret, and historicize her Heads of Women. In this way, I will compensate for the minimal rigorous research on individual artworks by Mallo and the excessive attention paid to her personality at the expense of her art. I do so by means of reconstructing the complexity of her ideas and presenting her work as the result of a nuanced artistic process, carefully selected sources, and novel approaches to them. Her very personal process entailed drawing from multiple references and allowed her to introduce race and gender-related themes into the sphere of Spanish modern art.

[1] During her life, Mallo’s work generated much attention, in both the Spanish press and the different places where she exhibited (Buenos Aires, Montevideo, Rio de Janeiro, New York…). She kept records of the press clippings talking about her and the list is impressive. Even though she never proclaimed herself as such, she has become and an emblem of feminism and female freedom.

[2] For instance, in 1979, she presented an anthological exhibition at the Galería Ruíz Castillo in Madrid. Juan Pérez de Ayala and Francisco Rivas, eds., Maruja Mallo (Madrid: Galería Guillermo de Osma, 1992): 28.

[3] Some relevant publications about Mallo’s art in English are Candelas Gala, “Creative Measurements: Plastic-Dynamic Development in Maruja Mallo’s Naturalezas Vivas,” chap.3 in Creative Cognition and the Cultural Panorama of Twentieth-Century Spain, 69-96. New York, Palgrave Macmillan, 2015; Shirley Mangini, “From the Atlantic to the Pacific: Maruja Mallo in Exile.” Studies in 20th and 21st Century Literature 30, no. 1 (2006): 85-106; “Cinematic Art, Maruja Mallo and Modern Visual Culture.” Journal of Spanish Cultural Studies 12, no. 4 (December 2011): 463-487; Josefina González Cubero, “Photographs of Theatre that Could Not Be. Maruja Mallo’s Stage Designs.” Valladolid: Universidad de Valladolid, Escuela de Arquitectura (November 2014): 203-220; Roberta Ann Quance, “Maruja Mallo and the Interest in Children’s Art during the Second Spanish Republic,” Bulletin of Hispanic Studies 90, no.7 (2013): 803-818; Eamon McCarthy, “Images of the mujer moderna in the Works of Maruja Mallo and Norah Borges,” Bulletin of Spanish Studies 95, no.5 (2018): 455-478; Anna M. Wieck, “Maruja Mallo’s Verbenas and Anti-Landscapes,” chap. 2 in Painting, Popular Culture, Putrefaction: Depicting Tradition on the Eve of the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), 53-99. PhD diss., University of Michigan, 2016.

[4] Consuelo de la Gándara, Maruja Mallo. Madrid: Servicios de Publicaciones del Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia, 1978; José Luis Ferris, Maruja Mallo: la gran transgresora del 27. Barcelona: Temas de hoy, 2004; Estrella de Diego, Maruja Mallo. Madrid: Fundación Mapfre, 2008; Fernando Huici March and Juan Pérez de Ayala, eds., Maruja Mallo. Madrid: Sociedad Estatal de Conmemoraciones Culturales, Ministerio de Cultura, Fundación Caixa Galicia, 2009 (vol. 1 includes texts by editors, and by María Escribano and Estrella de Diego); Shirley Mangini, Maruja Mallo and the Spanish Avant-Garde. Farnham, England: Ashgate, 2016.

In addition to these authors, I must mention gallerist Guillermo de Osma as an expert on the art of Maruja Mallo. His art gallery in Madrid has been a pioneer in organizing three exhibitions on Maruja Mallo’s art (in 1992, 2002, and 2017). Osma also acquired her archive, which was later transferred to the Archivo Lafuente (Santander, Spain) and he has promoted the catalog raissonné of Maruja Mallo’s paintings that is forthcoming from Editorial Nerea. The research group working in this project comprises Antonio Bonet Correa, Estrella de Diego, María Dolores Jiménez-Blanco, Fernando Huici, and José Carlos Valle.

Beyond curatorship and academia, it is worth mentioning the documentary on Mallo titled “Mitad ángel, mitad marisco” [Half Angel, Half Seafood] produced by filmmaker Antón Reixa in 2010.

[5] Estrella de Diego, Maruja Mallo. Madrid: Fundación Mapfre, 2008.

Web design: Esther Rodríguez Cámara, 2021