Conclusion

In October of 1948, Mallo exhibited in New York for the first time at Carrol Carstairs Gallery. That show included five of her Heads: Head of Black Woman (front and profile, 1946),[1] The Human Deer (front and profile, 1948), and another unidentified painting. The Spanish and Latin American communities of New York were invited,[2] and important American collectors attended too. She sold thirteen of the twenty-four paintings.[3] On the occasion of this successful exhibition, critics Zoila N. Villadeamigo, and Alfonso Sayons, respectively wrote:

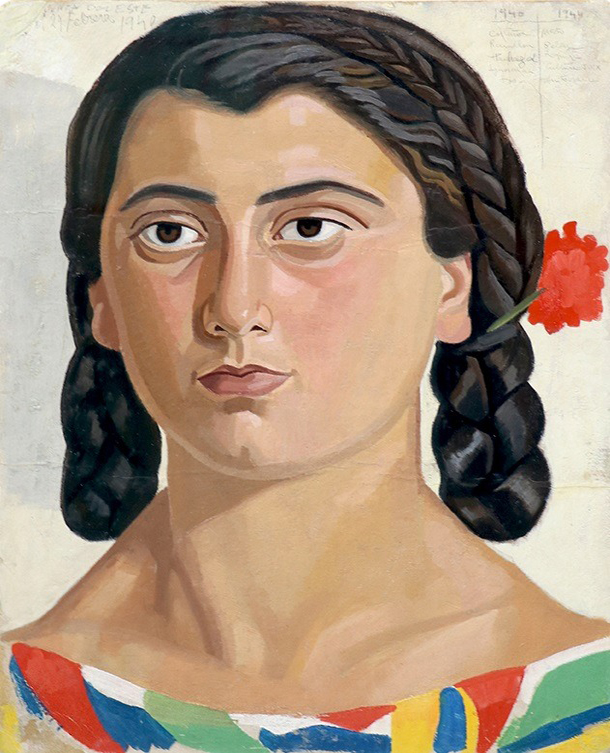

Maruja Mallo’s masterpiece is represented in her paintings of heads of the five races, with a very faithful tone of the color and form that characterizes the races. In this work, considered an incomparable novelty in modern pictorial art, the artist has masterfully grasped the racial archetypes in an artistic way, in the humanized order that corresponds to each race.[4]

Those who, like me, know this country [the US] and its mindset quite well, (…) believe, indeed, that once again the Spanish fire has rallied with all its strength and genius against the silent, grey and impersonal wall and has knocked it down. Even more, it has scared it. And fright sometimes proves more than admiration. Furthermore, coming young to a country that believes to be young but that it is very old, without painting “a la Picasso” or “a la Roualt” or “a la Modigliani” or “a la Miró” is a bold move. Coming to New York with the four best painted black heads we have ever seen (and black!) is too much. Spain has been able to do it. And, over time, it will be able to do much more.[5]

Two years later, in March of 1950, Mallo exhibited works at Silvagni Gallery in Paris. There, she presented six of her Heads, including at least Head of Black Woman (1946, profile) and the Human Deer (front and profile). On this occasion, other contemporary critics also betray an interesting account of these paintings’ reception. For instance, Bernard Dorival, curator of the Modern Art Museum of Paris, described the paintings as “extraordinary racial heads.”[6] And Charles Oulmont, President of the World Critic, wrote the following for a Finish newspaper after seeing the exhibition:

…But most of all, we are fascinated by her series of different faces; unlike many other artists who try by all means to deprive mankind of its humanity, she seems to humanize matter by humanizing herself to create a calm new world; a world where it would be a pleasure to live if we could. The world of disembodied souls, a world known for tenderness and compassion…We must, with every reason, be grateful to the artist who takes us out of the reach of present misery and all worldly wit.”[7]

Close attention to the reactions the Heads received reveals that the critics who saw them perceived the paintings as an innovation within the contemporary art landscape. Furthermore, they seemed shocked, as if it was difficult to understand how Mallo ever thought of depicting the racial diversity of Latin America. Sayons remarked with a tone of surprise that the ones that Mallo exhibited in New York were the best paintings of Black women that he had seen. He also implied that the paintings nearly “scared” the public, and he suggests that that fright was more telling than admiration. Admiration can be defined as the feeling of being surprised by something extraordinary or unexpected, but it also connotes a special and pleasant liking towards what you observe; however, to scare implies that something is felt as a kind of threat. This mix of admiration and shock registers critics’ and audiences’ difficulties in acknowledging the idea the paintings expressed (the beauty and equality of all races). That Mallo chose to send to New York and Paris some of these Heads as a representation of her body of work was, then, a daring decision. The critics’ reactions suggest that some of the Heads were received on the terms that Mallo intended. Her audience perceived the statement on race that she was making and was shocked by it. Would their reactions had been the same had Mallo exhibited Head of Woman (1941) instead, the only one with more clear Caucasian features? [8]

It appears that Mallo was ahead of her time and possibly preparing the potential audience for her Heads, both in a European and in an American context, to experience pictorial themes in the arts that they were still not used to seeing. In some ways, Mallo, who enjoyed being called “a sibyl,”[9] and considered painting to be “the most prophetic of the Fine Arts,”[10] worked here as an artistic clairvoyant. She recognized, as did others in her day, the diversity of Latin American populations and addressed it in her work. In the process, as discussed in this project, she wrestled with inner contradictions and with a historic and cultural context that still perpetuated gender bias and racism, both about women and about people of color. Though essentializing in some respects and forward-looking in others, this series demonstrates the unmistakable significance of race in modern Spanish art, where the topic remains understudied.

[1] Head of Black Woman (1946) received the First Painting Prize in the XII Exhibition of New York in 1948.

[2] Sonia Ellis, “Exhibición pictórica de Maruja Mallo,” El Diario de Nueva York (October 8, 1948). Press clipping. Archivo Maruja Mallo.

[3] Mangini, “From the Atlantic to the Pacific,” 181.

[4] My translation. Original text in Spanish: “La obra maestra de Maruja Mallo está representada en sus cuadros de cabezas con las cinco razas, con tonalidad muy fiel en color y la forma, que caracteriza a las razas. En este trabajo, considerado una novedad incomparable en el arte pictórico moderno, la artista ha captado magistralmente los arquetipos raciales plásticamente, en el orden humanizado que corresponde a cada raza.” Zoila N. Villadeamigo, “Visitó nuestra redacción la eximia pintora española Maruja Mallo,” Nueva York al día (October 16, 1948). Transcribed in Maruja Mallo: Orden y Creación, 90.

[5] My translation. Original text in Spanish: “Los que conocemos este país bastante bien, y esta mentalidad (que al decir de un amigo no es tal mentalidad sino “un estado de cosas”) creemos, decididamente, que una vez más el fuego español ha arremetido con toda su fuerza y su genio contra la muralla silenciosa, gris, impersonal y la ha derrumbado. Más aún, la ha asustado (…) Y el susto prueba a veces más que la admiración. Además, el venir joven a un país que se dice joven y es (o está) viejísimo, sin pintar “a la Picasso” o “a la Roualt” o “a la Modigliani” o “a la Miró” es una desfachatez. Eso de venirse a Nueva York con las cuatro cabezas de negras mejor pintadas que hayamos visto (¡y negras!) es demasiado. España lo ha podido hacer. Y podrá, con el tiempo, mucho más.” Alfonso Sayons, “Maruja Mallo en Nueva York,” España Republicana, Buenos Aires, 25 de diciembre de 1948 (from newspaper clipping kept as part of Maruja Mallo’s archive). Also published in Para Ti (December 14, 1948): n.p, and translated in Galician in: Maruja Mallo (Santiago de Compostela: Centro de Arte Contemporáneo de Galicia, 1993): 301.

[6] Bernard Dorival. Quoted in M.Mallo: catálogo exposición 88 (Buenos Aires: Galería Bonino, 1957): n.p.

[7] My translation. Original text in Finish: “Mutta enen kaikkea meitä viehättää hänen erilaisia kasvoja esittävä sarjansa; päinvastoin kuin monet muut taitellijat, jotka yrittävät kaikin keinoin riistää ihmiseltä hänen inhimillisyyttään, hän näyttää inhimillistämällä ainetta onistuvan luomaan tyytin uuden manilman; mailman, jossa olisi ilo eläa, jos silhen kykenlsimme. Ruumiittomien sielujen maailman, maailman, jossa tunnetaan hellyyttä ja sääliä… Meidän on täydellä syyllä oltava kiitollisia taiteilljalle, joka vie meidät nykyisen kurjuuden ja kaiken maallisen sukeuden ulottuvilta.” Charles Oulmont, “Pariisin taide-elämää,” Helsingin Sanomat, no. 141 (May 28, 1950): 14.

[8] This did not happen because that pair of paintings had been acquired by the Museo Rosa Calisteo of Santa Fe (Argentina) in 1946 and they were not exhibited again until 1993 in Spain.

[9] When Mallo was young, her friend Ramón Gómez de la Serna nicknamed her “la brujita joven” [the young little witch], but she said to him that she preferred to be called a “sibyl” because this was a more “Mediterranean” term. Gómez de la Serna agreed with her and added that “sibyl” was also a more “universal” term. Maruja Mallo, “Entrevista con Maruja Mallo,” interview by Fernando Huici, Camp de l’arpa, no. 53-54 (1978): 29.

[10] Amelia Meléndez Taboa, “Escritos últimos y erráticos de la artista Maruja Mallo,” Locas, escritoras y personajes femeninos cuestionando las normas: XII Congreso Internacional del Grupo de Investigación Escritoras y Escrituras (2015), 1047.

Web design: Esther Rodríguez Cámara, 2021

![Maruja Mallo. "Blonde Woman" or "The [Male] Champion," 1951.](https://edspace.american.edu/marujamalloheadsofwomen/wp-content/uploads/sites/1773/2021/02/mujer-rubia_1951_marujamallo.jpg)