HOME › PART 1: The Search of Ideal Beauty › The “Living Mathematics of the Skeleton”

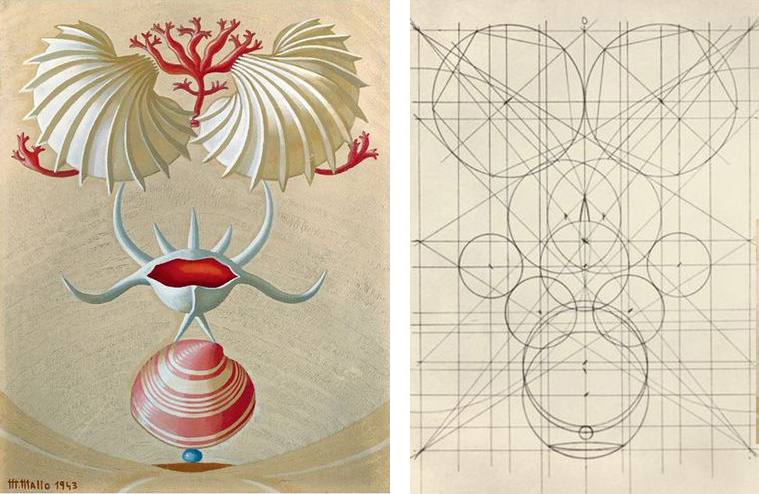

Mallo’s Heads of Women exhibit a sense of classical beauty that was achieved by the artist’s painstaking attention to anatomical proportions and geometry. That combination of proportionated measurements, grids, circumferences, straight lines, angles, and curves is what constitutes the foundational structure from which the faces were constructed. Although none of the outlines of the thirteen Heads that I consider part of the series are preserved, an exploration of other anatomical drawings and diagrams that she made reveals the thoughtful work that underlines her paintings. The artist titled the complex geometrical diagrams used in her artworks from circa 1939 “trazados armónicos” [harmonic outlines]. For instance, figure 24 show Mallo’s painting The Song of the Spikes together with the harmonic outline that she used to compose it, while in figure 25 we see an example of a harmonic outline for one of Mallo’s Naturalezas Vivas. In the artist’s drawings Portrait in Frontal and Profile View and Perspective of Cube and Head we can appreciate how carefully the artist studied facial proportions and the geometrical relationship between frontal and profile views (Figs. 23 and 26). In the Heads series, in those portraits that form pairs, such as Head of Woman (1941), Head of Black Woman (1946) The Human Deer (1948), or Polynesia (1951), Mallo likely achieved correspondence between the front and profile views by using the kind of parallel lines, proportions and measurement annotations that we see in her other sketches. (Figs. 27-28)

Since the 1920s, when Mallo was living in Madrid, different authors and theories with which she was familiar proclaimed geometry as the fundamental basis for any new form of art. Mallo, an avid reader, and a tirelessly curious mind, learned from them and adapted them for her own purposes. In the Heads series, her adoption of a classical beauty based on geometry and proportions enabled her to create a collective image of ideal female beauty grounded in timeless idealism. Moreover, through geometry and proportions (especially the golden ratio), she sought to achieve harmony and balance, qualities that the theories she studied claimed were the unchanging “skeleton” of all humans. Geometry and proportional ratios were in opposition to the more personal, mutable, modern, and playful quality of makeup and hairstyle.

If “harmonic outline” is the name that Mallo gave to her careful preparatory drawings, the concept of “la matemática viviente del esqueleto” [the living mathematics of the skeleton] [1] is the overarching artistic concept that Mallo created to describe her interest in the geometries inherent to the structure of the human body. Fernando Huici theorized that Mallo was inspired by a book by Romanian mathematician Matila Ghyka titled Esthétique des proportions dans la nature et dans les arts (1927).[2] In it, Ghyka, pursuant to previous theories by Jay Hambdige,[3] analyzed the relationship between art and nature and claimed that the best way to study the mathematics inherent to the processes of development and change in nature was through direct study of the human skeleton.[4] Mallo not only read and annotated the book itself, but she also synthesized the ideas she gleaned from it once she arrived in Argentina. In a notebook that is also preserved in her archive, she reproduced drawings and diagrams included in Esthétique, as well as her own translations of excerpts of the book into Spanish.[5] (Fig. 29)

What these drawings of human skeletons reveal is her interest in studying and depicting the human figure through the use of front-and-profile views and the application of the golden ratio, which are the two fundamental formal resources that she employed in her Heads, and that allowed her to achieve a sense of anatomical perfection For example, in the page of Esthétique placed next to the plate from which Mallo copied the diagrams, Ghyka wrote that “[Jay Hambidge] noted in each skeleton measured from the front and in profile a harmonic rhythm of rectangles always related to those of modulus √5 and Φ.”[6] In other of his books, Le nombre d’or: rites et rythmes pythagoriciens dans le développement de la civilisation occidentale (1931), Ghyka included an image of Miss Helen Wills and another of Da Vinci’s portrait of Isabel d’Este to examine how they follow the golden ratio (Fig. 30). In the case of the former, Ghyka used a diagram similar to those employed by Mallo and called it “harmonic analysis.”[7] The harmonic outlines that Mallo employed on her Heads were probably very similar to those visible in preparatory drawings like those in figures 23-26.

Another contemporary theory that seems especially relevant to Mallo’s conception of Heads was introduced by Spanish writer Eugenio d’Ors in Tres Horas en el Museo del Prado [Three Hours at the Prado, 1922], a book that Mallo likely knew, as she attended D’Ors’s lectures in Madrid.[8] In it, he argued that both a “spatial value” (the domain of pure geometry) and an “expressive value” (the domain of meaning) were essential elements of the “artistic form.”[9] In other words, according to him, an artwork is composed of two symbolical components, one that relates to how the image is spatially and structurally composed, and another that corresponds to the subjective or emotional meaning that it transmits. This idea helps to explain the equal emphasis that Mallo placed on the Heads’ mathematical structure (which corresponds to D’Ors’s concept of spatial value) and to the seemingly more superficial aspects of glamour (the “expressive” component) in her construction of ideal beauty.

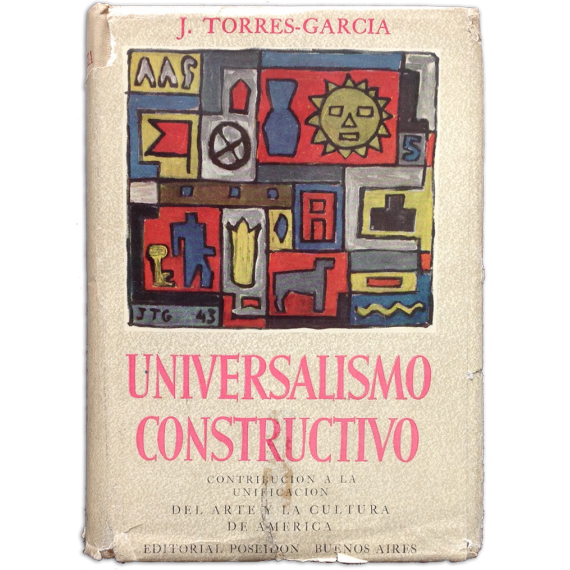

Following a line of thought close to D’Ors’ understanding of the two necessary components of a work of art, Uruguayan artist Joaquín Torres García developed a body of theories that deeply impacted Mallo, who knew him in person.[10] The underlying principles of Torres García writing, presented in books such as Estructura (1935) and Universalismo Constructivo (1944), were a primary source of inspiration for Mallo’s Heads of Women, but she reinterpreted and expanded upon his theories in a personal way. Although Torres García defended the role of figuration and description, he paradoxically gained artistic success through artworks that are almost abstract. By contrast, Mallo took a different approach. She brought some of his ideas into figurative representation, which enabled her to imbue her subjects with political and ethical connotations.

Fernando Huici points to Estructura (1935) as the book by Torres García that Mallo surely read and, indeed Mallo’s archive includes a notebook in which she made her own summary of Estructura, a book in which Torres García developed the concept of structure. According to him, structure is the universal abstract rule that provides an artwork with unity and cohesion and that unites all cultures across all time.[11] His book Universalismo Constructivo (Fig. 31) further elaborated on this concept and sought to explain his notion of a “universal constructivist” art based on a geometric structure existing both in ancient and modern cultures.[12] He also claimed that curves, straight lines, angles, circumferences, and arcs are the “few universal elements with which everything can be expressed,”[13] and emphasized art’s need to return to “timeless fundamental rules” while at the same time incorporating modernity:

We should clarify something very important: that entering again in the Tradition does not imply or mean returning to the antique (…), but to the timeless fundamental rules, and then [,] with them (…) say what we have to say today.[14]

Thus, we should (…) feel the qualities of today’s objects, harmonize with everything that could mark a modern aspect. (…) And then, we find in the artwork that on the one hand we have all that is evolving, changing, and on the other hand the deep element of the eternal, the law, what is invariable. That is, in fact, what happens in reality.[15] (emphasis by the artist)

Interestingly, Torres had difficulty in finding a way to apply his theory to his own work. He struggled to decide whether he should only use abstract forms in a painting (and therefore lose that modern element of today) or combine completely figurative and abstract forms (which for him implied losing the best qualities of each). He ended up adding simplified figurative forms and graphic symbols to his schematic, grid-based abstract paintings.[16] With her Heads, Mallo seems to have grasped a way to better combine both elements without having to separate them on canvas. In other words, she did not mix geometrical elements with quasi-figurative ones, but instead fused them, like bone and skin in real bodies. In her Heads, Mallo used geometry and ratios to create underlying harmonic outlines that served as the invisible, shared, and timeless skeleton or structure of these women. However, she constructed volume through careful use of light and color which allowed for the exaltation of their different skin tones and hairstyles and gave them a more modern style.

Figure 24. Up: Maruja Mallo. El canto de las espigas [The Song of the Spikes, 1939]. Oil on canvas, 118 x 233 cm. Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía. Down: “Harmonic outline” of The Song of the Spikes.

Figure 25. Maruja Mallo. Naturaleza Viva [Living Nature, 1943] and its corresponding “harmonic outline.”

Figure 26. Maruja Mallo. Perspective of Cube and Head, 1936-1937. Pencil and color pencil on paper, 21.5 x 49 cm. Archivo Maruja Mallo/Archivo Lafuente.

Figure 27. Maruja Mallo. The Human Deer (1948) © Maruja Mallo

Figure 28. Maruja Mallo. Bidimensional Portrait, September 1947. Pencil on paper, 9 x 16 cm. Archivo Maruja Mallo.

Figure 29. Drawings, diagrams, and annotations by Maruja Mallo, Buenos Aires, 1937. They are a synthesis of Matila C. Ghyka’s Esthétique des proportions dans la nature et dans les arts.

Figure 30. Harmonic analysis of a photo of Miss Helen Wills, following the golden ratio. In Matila Ghyka, El número de oro, tomo I (Buenos Aires: Poseidón, 1984): Plates XIX and XX, p. 72-73.

Figure 31. Cover of the first edition of Joaquín Torres García’s Universalismo Constructivo. Buenos Aires: Poseidón, 1944.

[1] It is worth noting that in Spanish, the word “esqueleto” can be used both to refer to animals and humans’ skeleton and to the frame/structure that is holding something.

[2] Fernando Huici March, “Maruja Mallo, con el cerebro en la mano,” in Maruja Mallo, edited by Fernando Huici March and Juan Pérez de Ayala, vol 1 (Madrid: Sociedad Estatal de Conmemoraciones Culturales, Ministerio de Cultura, Fundación Caixa Galicia, 2009), 38.

Mallo’s own copy of the book, full of handwritten annotations, was discovered by the Spanish art critic and curator Juan Manuel Bonet in the Madrid flea market and is now part of his library. Juan Manuel Bonet, “Recordando a una gran pintora: Maruja Mallo,” Cuadernos Hispanoamericanos, no. 671 (2006): 36.

[3] Jay Hambidge (1867-1924) was an American artist who formulated the theory of “dynamic symmetry,” a method of proportioning spaces that he opposed to the notion of “static symmetry.” He developed it after studying “natural form and shapes in Greek and Egyptian art.” To know more about this theory see Jay Hambidge, Dynamic Symmetry: The Greek Vase. Yale University Press, 1920.

[4] Matila Ghyka, Esthétique des proportions dans la nature et dans les arts (Paris: Gallimard, 1927): 260. Mentioned in Huici March, “Maruja Mallo, con el cerebro en la mano,” 40.

[5] Not having been translated at that time, Mallo’s book was in French, which is another evidence of her interest in Ghyka’s theories, as she needed to make an extra effort in reading and understanding it.

[6] My translation. Original text in French: “Il [Jay Hambidge] constata dans chaque squelette mesuré de face et de profil un rythme harmoniqye de rectangles toujours apparentés à ceux de module √5 et Φ.” Ghyka, Esthétique, 260.

[7] These images correspond to plates xix-xxi in Matila Ghyka, El número de oro (Barcelona. Poseidón, 1978). Fernando Huici used these examples as evidence of Mallo reading this book, suggesting that she could have been inspired by them to paint her Heads of Women. Huici, “Maruja Mallo con el cerebro en la mano,” 60.

[8] Mallo’s friend Concha Méndez wrote in her memoirs that they both attended Eugenio d’Ors lectures. Ulacia Altolaguirre, Memorias habladas, 51.

[9] Eugenio d’Ors. Tres horas en el Museo del Prado (Madrid: Aguilar, 1957), 27. (I have accessed the 1957’s edition, but the book was first published in 1922).

[10] Born in Uruguay, Torres García spent three decades in Spain and lived in Paris in the 1920s. According to Fernando Huici, who wrote an extensive study on the relevance of Torres García ideas on Mallo’s art, both artists held individual exhibitions at Pierre Loeb gallery in Paris, and it is very plausible that they first met there in 1932, although García also lived in Madrid from 1933 to 1934. As stated in Torres García’s diaries, Mallo frequented his studio during that time. Huici, “Maruja Mallo, con el cerebro en la mano,” 36-37. Mallo also attended the Uruguayan artist’s lectures in Madrid. Shirley Mangini, Las modernas de Madrid: Las grandes intelectuales españolas de la vanguardia (Madrid: Ediciones Península, 2001), 132.

[11] Laura Murlender, “La escuela de Joaquín Torres-García y su tesis americanista: buscar a América,” Diversidad no.9 (December 2014): 48.

[12] “¿Por qué Universalismo Constructivo? Universalismo porque el arte tiene esencia universal, y Constructivo porque será la estructura la que domine toda la obra. En su libro trata de hacernos ver que hay un arte absoluto, universal, y que su esencia es una regla o ley que siempre se mantiene invariable aunque su plasmación sea diferente según las épocas.” Durán Úcar, “Joaquín Torres García: crear un orden,” 28-29.

[13] Torres García, Universalismo Constructivo, 75.

[14] My translation. Original text in Spanish: “Hay que aclarar algo muy importante: que entrar de nuevo en la Tradición, no supone ni quiere decir volver a lo antiguo, “torniamo all’antico”, pero sí a las normas fundamentales de siempre, y entonces con ellas (como ha sido también siempre) decir lo que tengamos que decir hoy.” Torres García, Universalismo constructivo, 74.

[15] My translation. Original text in Spanish: “Debemos pues, buscar tono en todo lo que nos rodea, sentir su vibración, sentir las calidades de los objetos de hoy, armonizar con todo aquello que pueda marcar aspecto moderno. Y entonces nos encontramos en la obra, que si de un lado damos todo aquello que va evolucionando, cambiando, por otro damos el elemento profundo de lo eterno, la ley, aquello que es invariable. Que, si se mira bien, es lo que tiene lugar en la realidad.” Torres García, Universalismo constructivo, 75.

[16] Durán Úcar, “Joaquín Torres García: crear un orden,” 26.

Web design: Esther Rodríguez Cámara, 2021